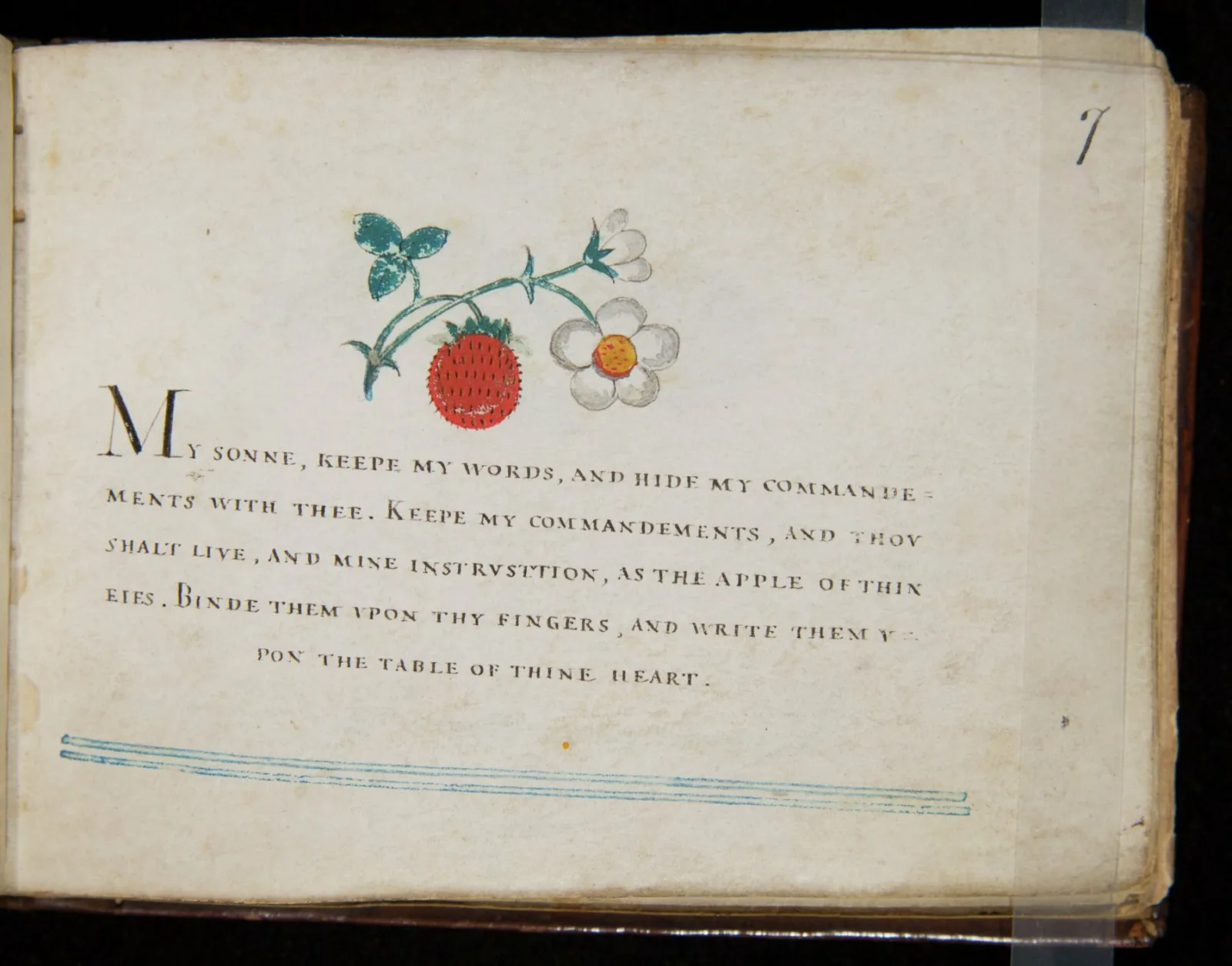

In the preface of his 1618 writing manual, the English writing master Martin Billinglsey (b. 1591) includes a response to those who think that it is unnecessary for women to learn how to write. He contends: “If any Art be commendable in a woman…it is this of Writing.”

His argument is based on three points. First, that women “not having the best memories…may commit many worthy and excellent things to Writing.” Second, that “secrets that are and ought to be, between Man and Wife, Friend and Friend, in either of their absences may be confined to their own privacy.” And finally, that “no woman surviving her husband, and who hath an estate left her, ought to be without the use [of writing].”

Billingsley ends his comments with the assertion that whoever “would barre women from the use of this excellent facultie of writing is utterly lame.”

While two of Billingsley’s reasons—bad memories and inability to refrain from shouting secrets—perhaps raise an eyebrow, his comments nevertheless underscore the fact that women (at least certain women) were taught to write in the early modern period. In fact, women are well-represented in my exhibition, A Show of Hands: Handwriting in the Age of Print.

One of my favorite items in the exhibition is Lucas Materot’s Les Ouevres (Avignon, 1608). Materot (b. 1560), a scribe in the papal chancery in Avignon, includes two pages of models specifically for women, noting that these examples are “easier” for the ladies. Curiously, these specimens look no different than those provided for men!

While I sometimes joke that Materot was compelled to provide these examples because he was so good-looking that he must have had scores of women hanging around the papal chancery, he was not the first Avignonnais writing master to publish gender specific models: Maurice Jausserandy’s Le Miroir (Avignon, 1600) also includes a page of lettering “suitable for the ladies.” Perhaps early 17th-century Avignon was overrun with forgetful, secret-revealing widows, or perhaps Jausserandy and Materot were attempting to carve out a niche in the crowded market of printed writing manuals. The fact that writing manuals offered models for women makes clear that writing masters had female students.

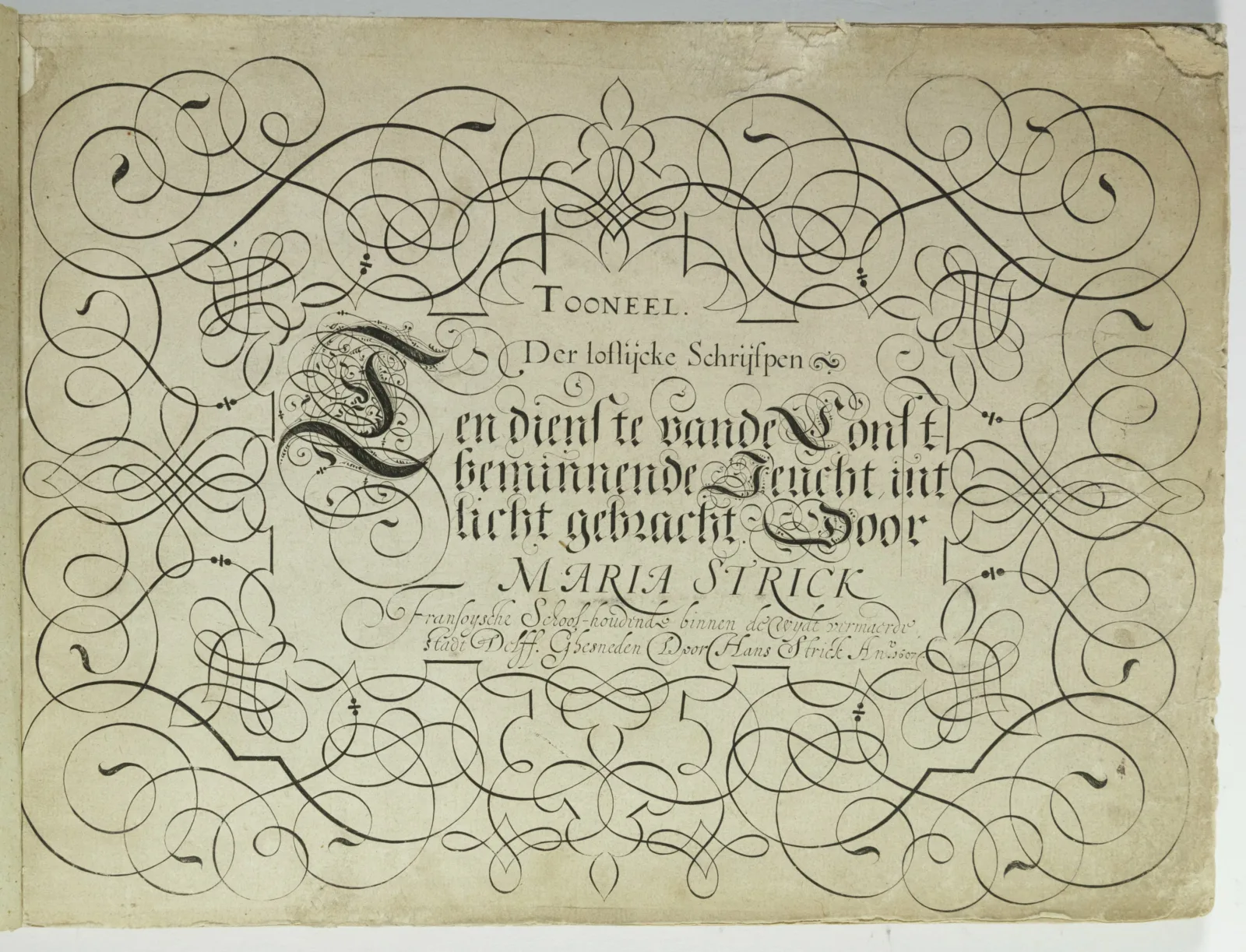

But contemporaneous with Materot and Jausserandy were the first writing books published by women. The best-known of these writing mistresses is Maria Strick (ca. 1577 – ca. 1625), who trained under the esteemed Dutch writing master Jan van den Velde and earned fame as a calligrapher by winning prizes in handwriting competitions. The winner of one such competition (a man) was so angry about the fact that she came in second (he said her placement was too heavily weighted in favor of her excellent italic) that he demanded a rematch. She refused.

Strick published four writing books in the early 17th century. The book on view in the exhibition, Tooneel der Loflijcke Schrijifpen (Theater of the Praiseworthy Pen), published in Delft in 1607, was engraved by Strick’s husband Hans, who gave up his career as a shoemaker to re-train as an engraver so that he could engrave her books. Strick was also the first woman to include an engraved portrait or herself in her books—a common practice for writing masters.

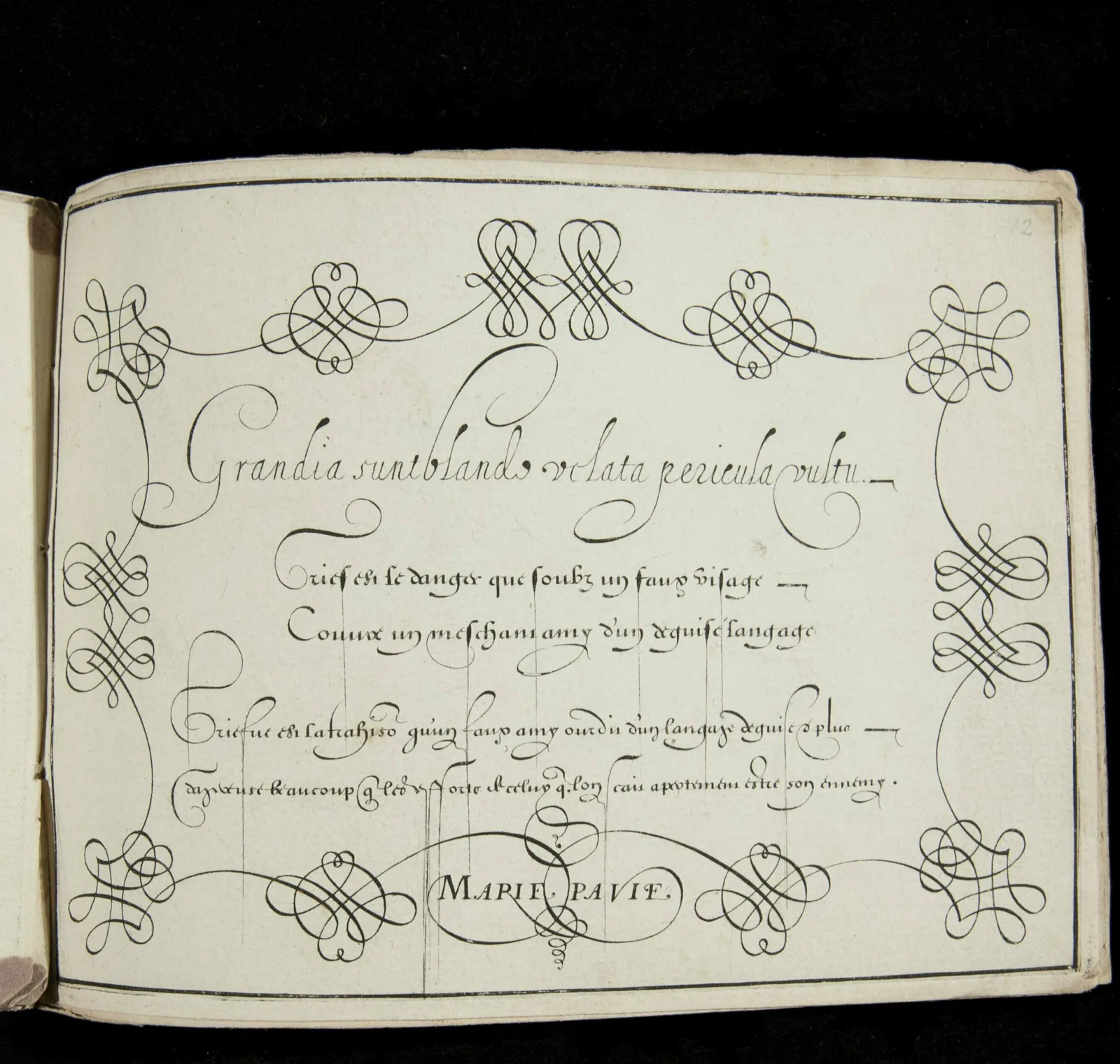

Slightly earlier than Strick was the Parisienne writing mistress Marie Pavie (fl. 1600), about whom little is known.

Unlike Strick, who was prolific, Pavie only published one writing manual, Le Premier Essay de la Plume de Marie Pavie (The First Attempt of the Pen of Marie Pavie), of which only two copies are known, both incomplete.

Her book was probably published around 1600, seven years before that of Strick. Unlike Strick, Pavie did not include a portrait of herself, although she did include wonderfully decorative variations of her name on every page. Neither Strick nor Pavie marketed their books specifically to women, possibly because they already catered primarily to female students.

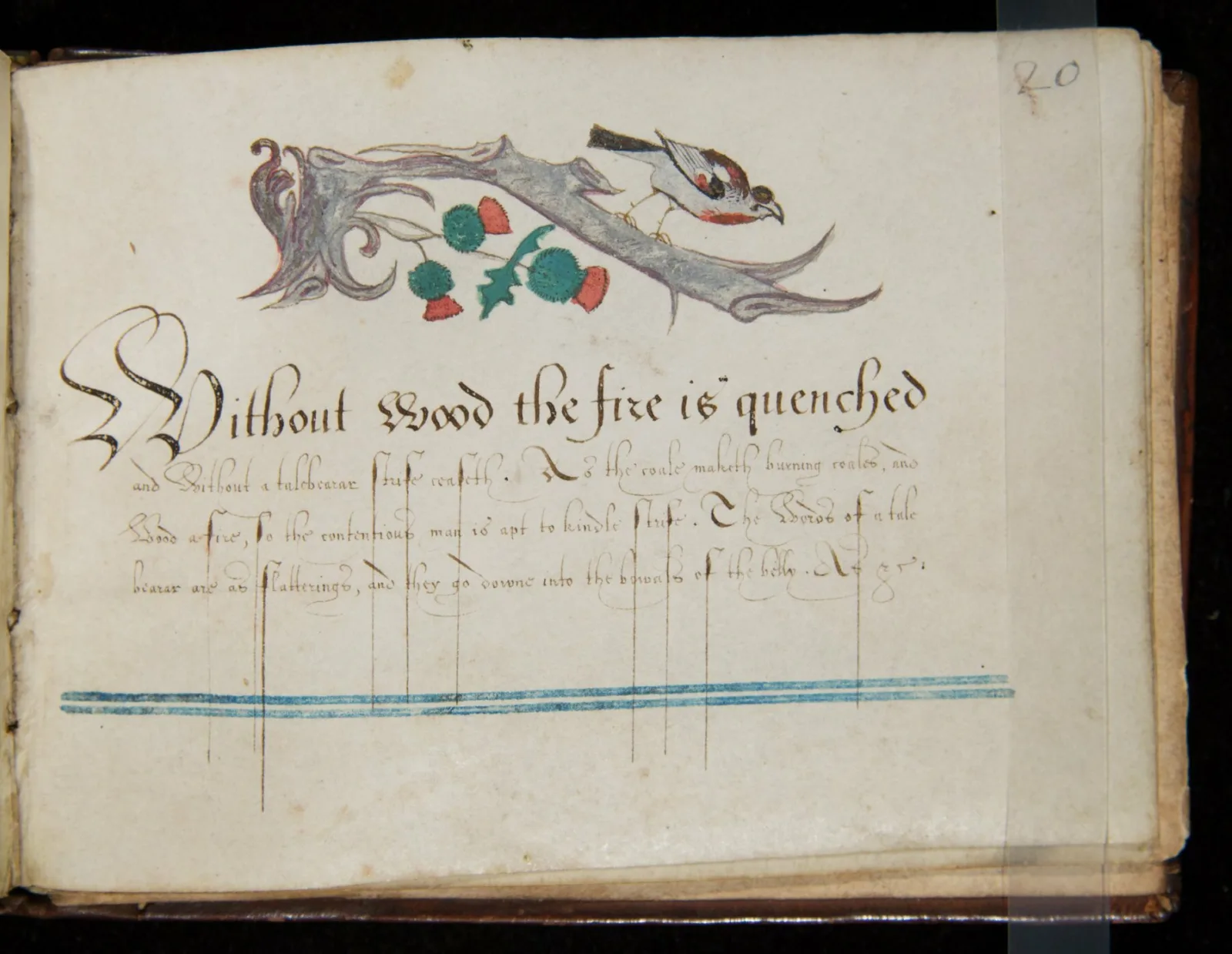

While we have only a few examples of writing books published by women (other female calligraphers, notably Esther Inglis, had successful careers working exclusively in manuscript), these books nevertheless provide evidence that women were taught to write and that they were active consumers—and creators—of writing manuals in the early modern period.

About the Author

Jill Gage is the Custodian of the Wing Foundation on the History of Printing. She is also the curator of A Show of Hands: Handwriting in the Age of Print. The exhibition is on view at the Newberry from September 9 - December 30, 2022.