On February 2, 1922, one hundred years ago, a bold blue novel appeared in the windows of Shakespeare and Company, a small bookshop on the Left Bank of Paris run by the American expatriate Sylvia Beach. The book was 732 pages, three inches thick, and already wildly controversial. No image or design appeared on the cover, simply ULYSSES, in white capital letters, BY JAMES JOYCE. It was the Irish writer’s fortieth birthday.

The next day, before the bookshop opened, a crowd had gathered in front of the Shakespeare and Company windows, eager to buy copies of a novel that had incited both admiration for its wild style and disgust with its “lewd” language. It may have been written in a heroic mode—tracking the one-day wanderings through Dublin of an Odysseus-like exile named Leopold Bloom and his surrogate son Stephen Dedalus. But Joyce also amplified the everyday, which meant an attention to the body’s habits and hungers.

Never before had defecation and masturbation been treated with such formal bravura.

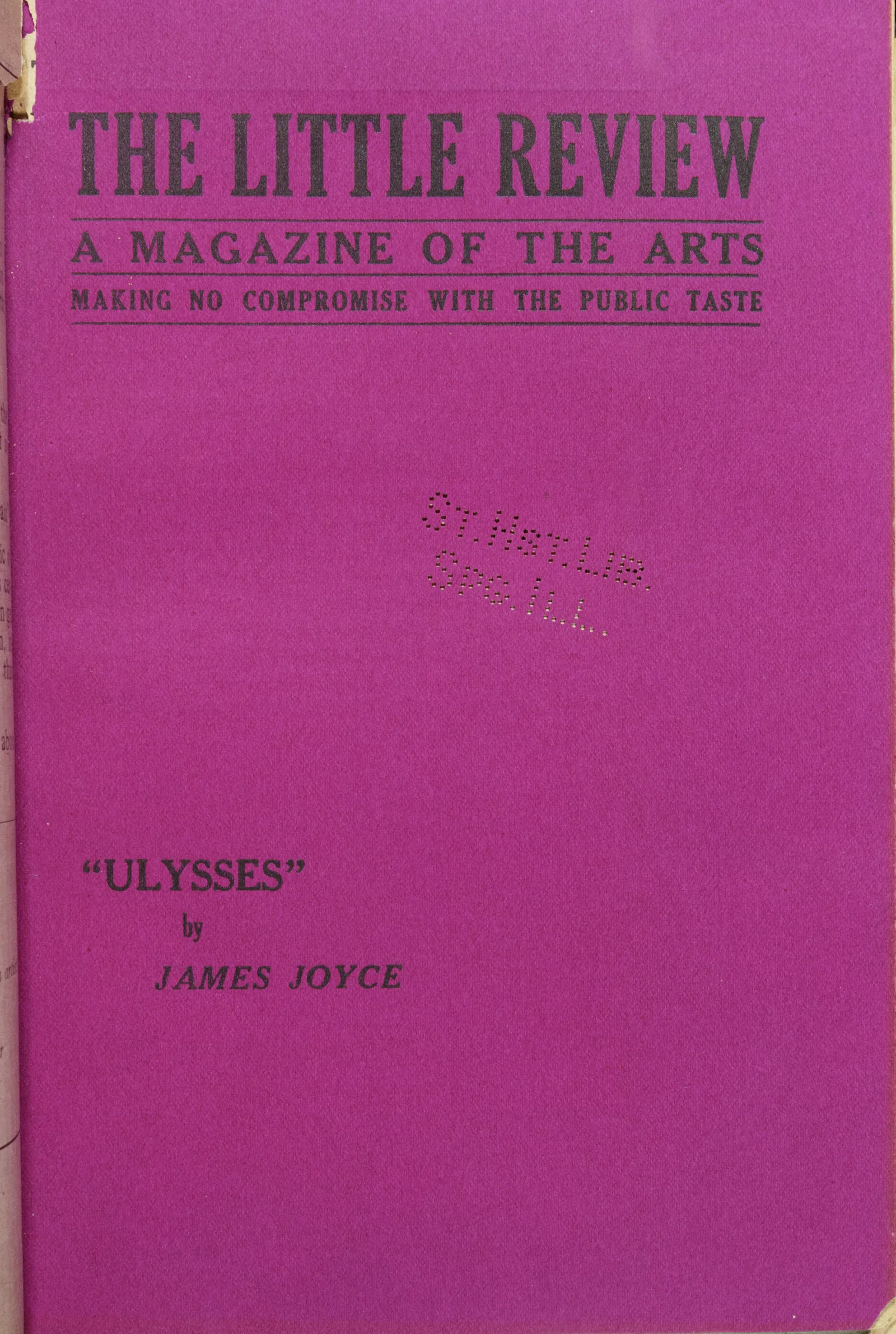

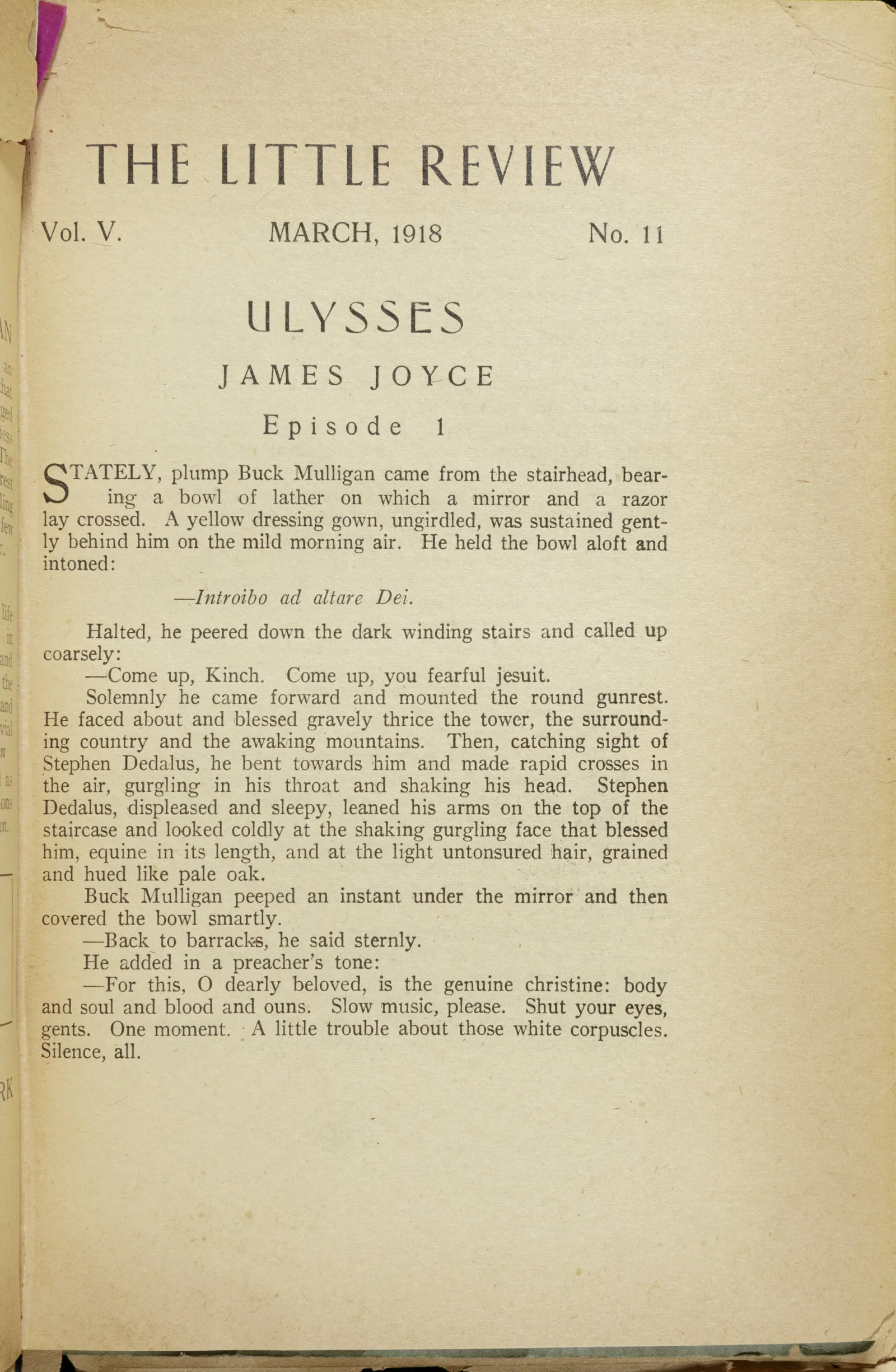

How did people already know about Ulysses? Thanks to a magazine founded in Chicago, many readers pored over monthly installments that began circulating in March 1918.

The magazine was called The Little Review—named after the literary innovations of the little theater movement in Chicago. Perhaps no magazine was as important to Joyce—and to literary modernism—as The Little Review. Its editors were two midwestern women, in love with each other, and with art and experiment. After publishing chapters of Ulysses in their magazine for almost two years, they would be charged with obscenity by the United States government.

Having fled small-town Indiana, Margaret Anderson launched The Little Review in 1914, publishing work by writers and provocateurs of the Chicago Renaissance and work from across the country and abroad. In the magazine’s first issue, Anderson was clear about the causes in which the magazine believed: “Feminism? A clear-thinking magazine can have only one attitude; the degree of ours is ardent!” In a 1915 issue, Anderson protested intolerance towards “inversion” in an editorial that is now understood to be one of the earliest defenses of homosexuality in America.

In 1916, Anderson met Jane Heap, a former student at the School of the Art Institute who dressed in trousers and neckties and infused the magazine with visual style. They advocated a culture of youth and rebellion, including Nietzschean philosophy and the anarchism of Emma Goldman, who inspired Anderson with her personal flare for combining politics and art.

The magazine’s association with Goldman drew the attention of government censors, who found the magazine both anarchistic and obscene. The Post Office first confiscated and burned issues of the magazine in October 1916, citing the immorality of a story about an unwed mother. Anderson was evicted from her apartment by a landlord who did not want to be associated with an anarchist. In 1917, the Espionage Act directed local postmasters around the country to inspect newspapers and magazines for material that would “embarrass or hamper” the war effort. The Little Review was under surveillance.

Anderson had always thrived on political intrigue and spectacle. After an early episode of economic instability, she camped out on the north shore of Lake Michigan for six months to save rent—a stunt that brought much attention to the magazine. Writers Ben Hecht and Maxwell Bodenheim walked miles up from the city to reach her on the beach and then pinned poems to her tent. Sherwood Anderson came out and told stories around the campfire. (Never mind that Margaret Anderson, statuesque and beautiful, was only attracted to women.)

Soon after, Anderson published an issue with mostly blank pages, which was her dramatic protest against a lack of acceptable submissions and an advertisement for more.

It was these blank pages—an incredibly bold move—that caught the eye of Ezra Pound, an irascible American writer at the center of a cadre of modernists in Paris, including Joyce. In February 1917, Pound sent Anderson and Heap typescripts of the first three chapters of Ulysses, hoping that they would not balk at its explicit sexuality and formal difficulty.

Anderson read the first two chapters straight through. She got to the third chapter, “Proteus,” an interior monologue of 22-year-old Stephen Dedalus, who walks along the beach at Sandymount Strand and thinks about Aristotelian concepts of perception. “Ineluctable modality of the visible; at least that if no more, thought through my eyes. Signature of all things I am here to read, seaspawn and seawrack, the nearing tide, that rusty boot.”

In her autobiography, Anderson describes how she read these words aloud, then cried out to Jane Heap: “This is the most beautiful thing we’ll ever have. We’ll print it if it’s the last effort of our lives.” From March 1918 to December 1920, the women published more than half of the novel in the pages of The Little Review.

Among its rich collection of Joyceana, the Newberry holds a full run of The Little Review, including these rare issues, which illuminate the process through which Joyce shaped the chapters of Ulysses into a novel. He expanded and edited the chapters dramatically in galley proof. Scholars have studied The Little Review’s chapters of Ulysses in relationship to the full novel, finding many extraordinary revisions, including Joyce’s wry propensity to make the final version, by the standards of 1922, even more “obscene.”

Anderson and Heap published thirteen of Joyce’s eighteen chapters before the United States Postal Office seized issues of the magazine. In question was “Nausicaa,” Joyce’s chapter written in the literary burlesque of women’s magazines. “His eyes burned into her as though they would search her through and through, read her very soul,” Joyce writes about a young girl Bloom watches from afar, while he masturbates on Sandymount Strand. Here is Bloom’s earthy anecdote to Stephen’s earlier grandiose pontifications on the same beach.

At this point, Anderson and Heap had relocated to New York City. (They would later move to Paris, where they met both James Joyce and Sylvia Beach). In New York, their lawyer was the art collector John Quinn—Pound’s friend—who had bankrolled The Little Review for many months. Quinn apparently told Anderson and Heap to remain “meek and silent” during the jam-packed obscenity trial, to surround themselves with “window trimmings,” Anderson recalled in her autobiography, which meant “conservative quietly-dressed women and innocent boarding school girls.”

The aura of male authority in the courtroom was comical and absurd. At one point, when the novel was to be read aloud, the judge took pause, worried that he would offend the ladies in the room, then assumed that the women could not understand what they had published.

Anderson and Heap were exasperated by Quinn and his strategy at the trial, which paid little heed to Joyce’s artistic genius. “I nearly rose from my seat to cry out that the only issue under consideration was the kind of person James Joyce was,” Anderson later wrote in her autobiography.” “But, having promised, I sat still.”

The Little Review lost. Like criminals, the women’s fingerprints were taken, and they were fined one hundred dollars. This seemed an enormous financial setback, until it was paid by a wealthy arts patron from Chicago appropriately named Joanna Fortune.

When the news of The Little Review’s trial arrived in Paris, Joyce was not surprised. A spiritual counterpart to Anderson and Heap, he embraced literary notoriety. He found another intrepid American woman in Sylvia Beach, who published the novel in a city known for being more libertine. Soon after his fortieth birthday, when more crates of Ulysses arrived at Shakespeare and Company, Joyce helped Beach fill orders and wrap packages of his book. He was exuberant, making a mess of the packing glue, which spread on the table, floor, and in his hair. As Anderson later wrote on about the debut and circulation of the novel in Paris, the “three-year propaganda” of The Little Review “began to have its effect.”

About the Author

Liesl Olson is Director of the Chicago Studies Program at the Newberry Library.