Scroll down for Spanish and Nahautl translations of the article.

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the Indigenous peoples of Mexico asserted their rights to land in the face of Spanish colonization.

At the time, the Spanish were imposing their own system of haciendas, ranches, and other mechanisms to regulate land tenure. In response to policies threatening Indigenous communities’ land, water, and autonomy, communities developed Techialoyan documents. These documents aimed to support Indigenous land claims in Mexico by documenting the founding and history of a town, illustrating long-established boundaries predating the arrival of Spanish colonists. Indigenous people used the documents as probate records to prove that their towns’ autonomy should be respected as cabeceras (judicial districts) under the Spanish system.

Ultimately, the documents aimed to safeguard and conserve Indigenous lifeways.

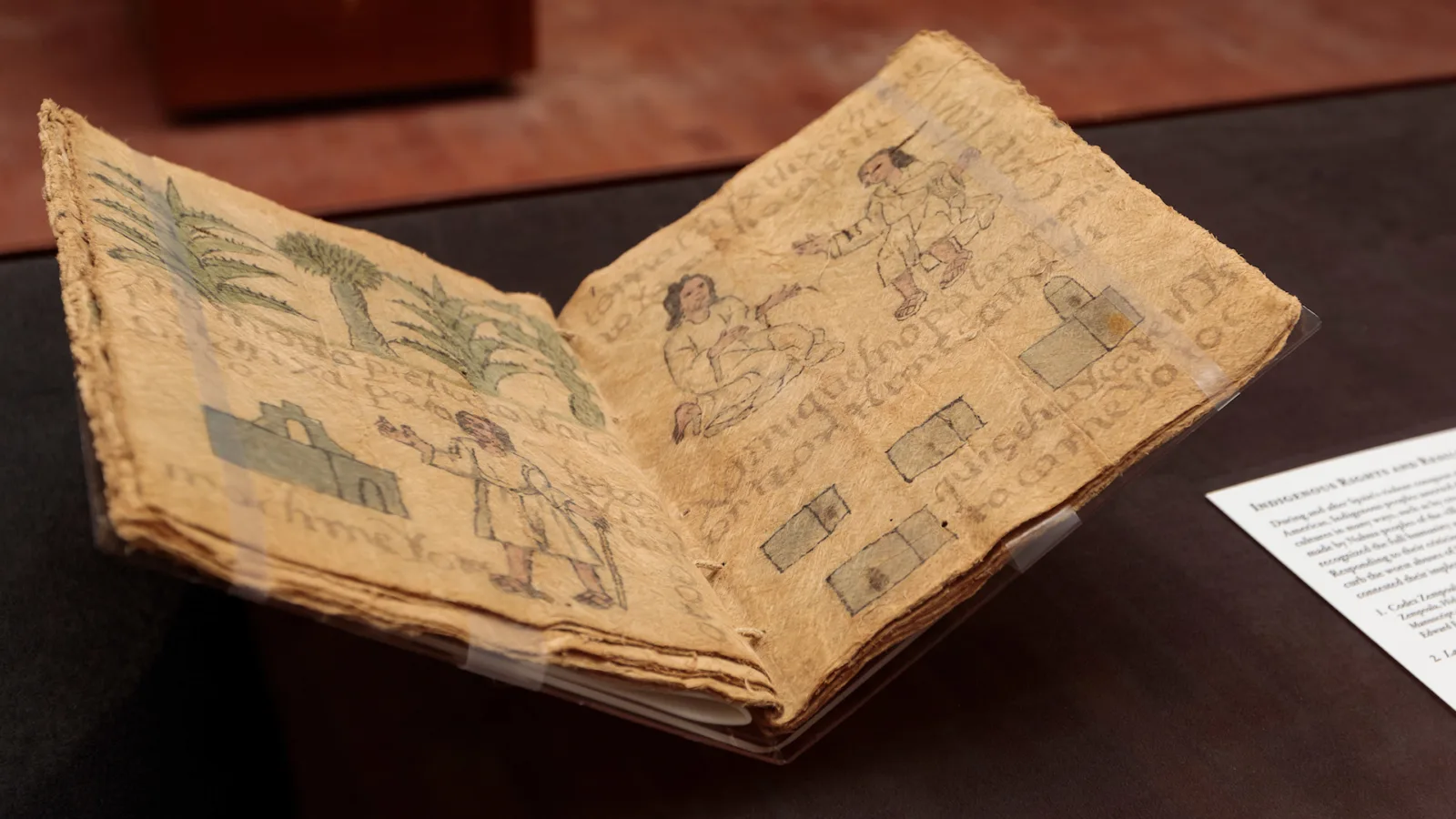

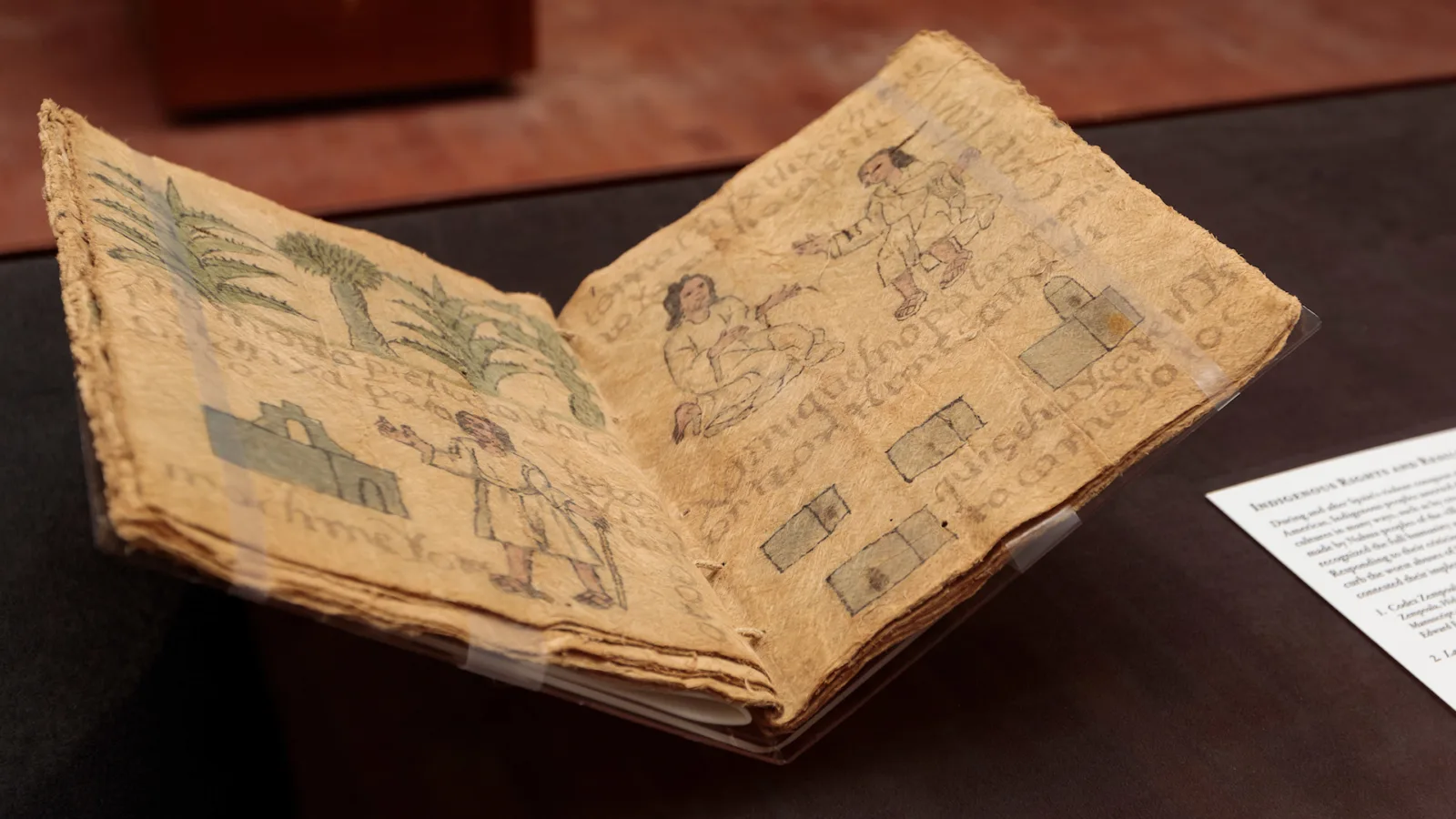

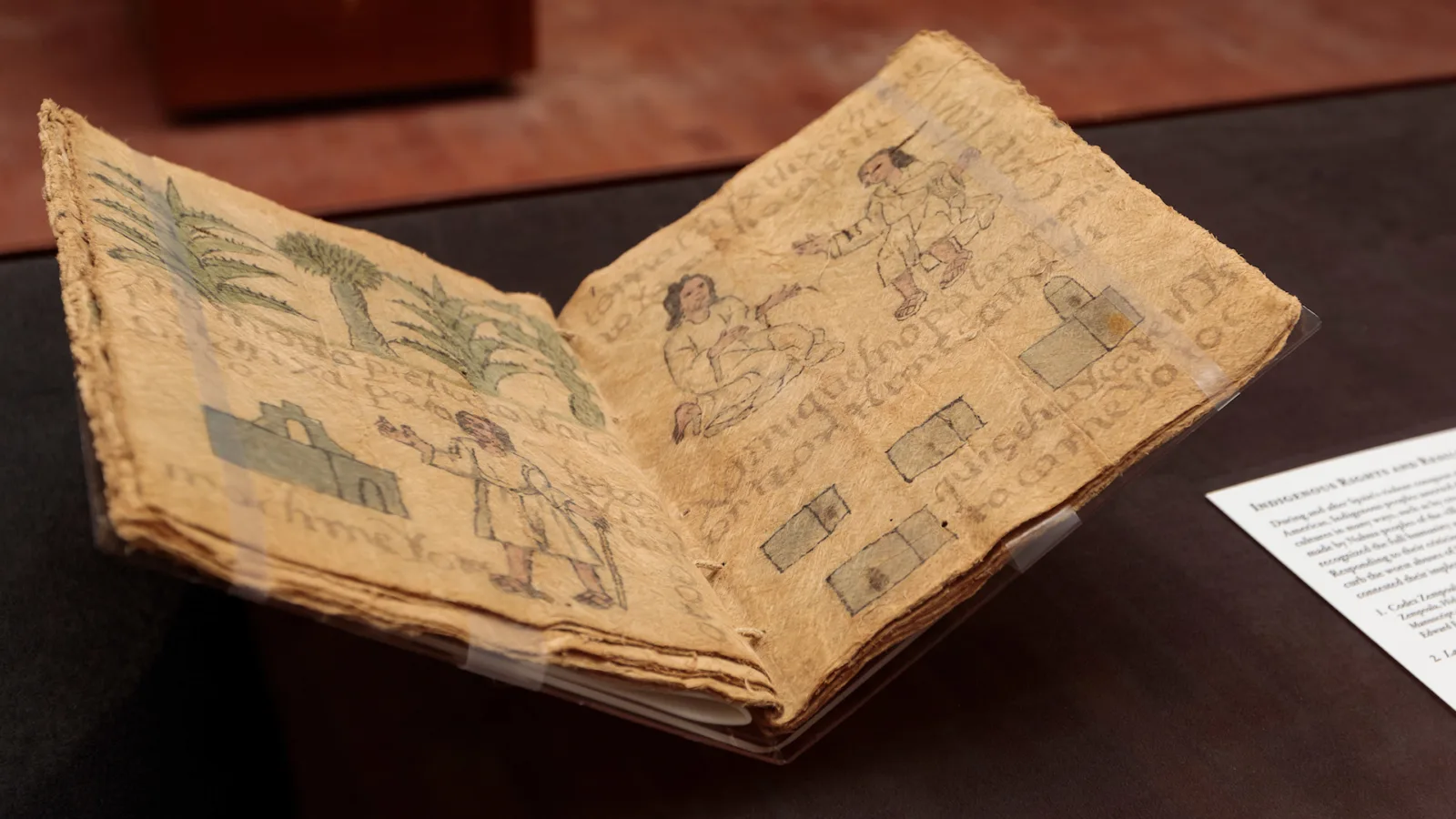

In total, there are about forty Techialoyan documents dating between the 17th and 18th centuries. Most utilize the Latin alphabet, but avoid using European paper; instead, they are made from Amatl (fig-bark paper), a type of Indigenous substrate. A good example of a Techialoyan is the the Codex Zempoala manuscript, produced sometime in the first half of the 18th century and housed at the Newberry as part of the Edward E. Ayer Collection related to American Indian and Indigenous Studies.

The Nahua people of the city of Zempoala in the state of Hidalgo, Mexico, asserted their rights through this document, a book that proved their long-standing relationship with the land. Some scholars, such as Stephanie Wood, have speculated that the document, like others of its kind, was designed to look older in order to further validate the long-established claims to the land. Since it does not look like a typical codex, the Codex Zempoala is often referred to as a “Village Land book.”

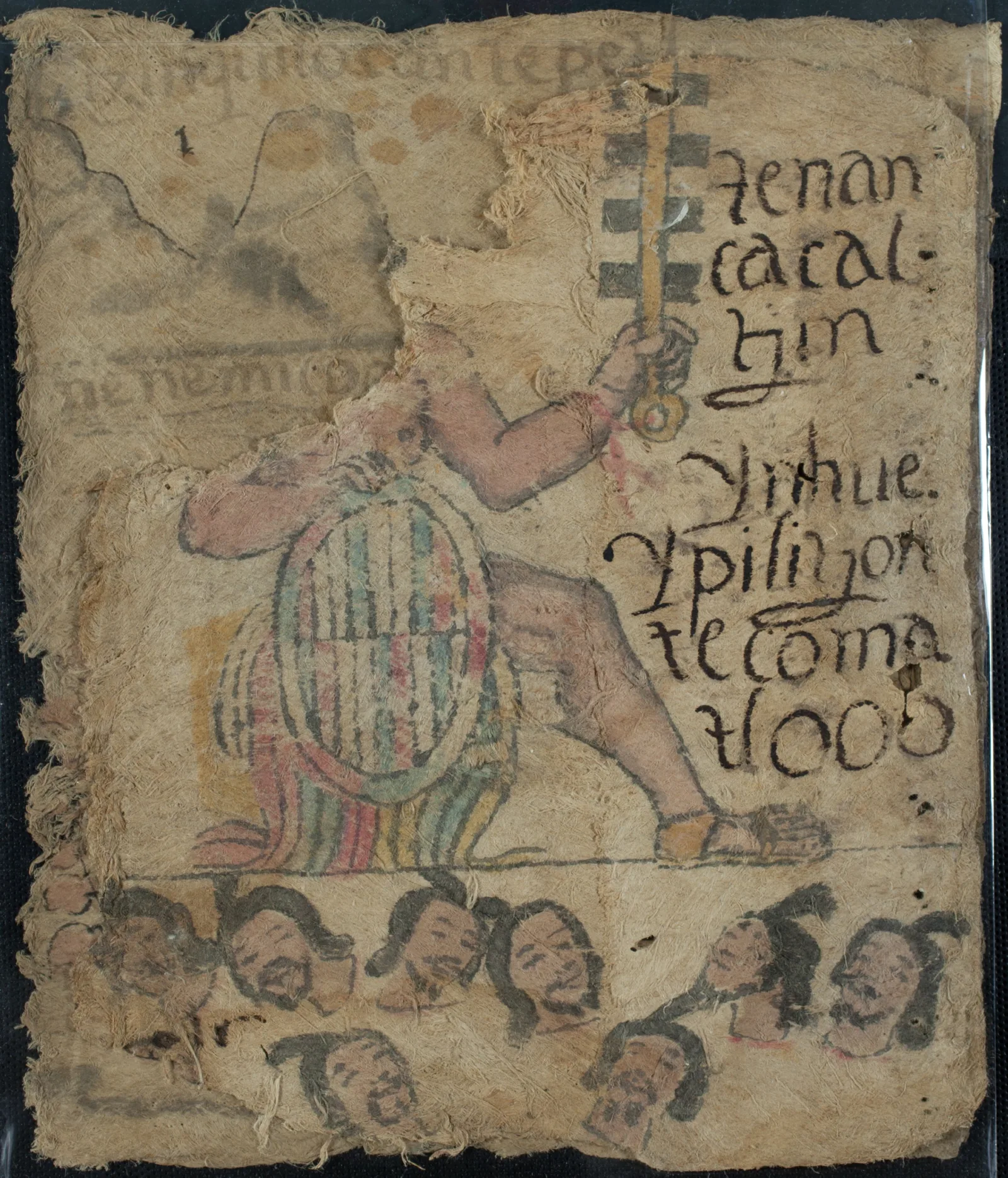

The majority of Techialoyan documents use common words and expressions throughout, often repeating such phrases as Nenehmi coaxohtli (Spanish: camino al pie del bosque; English: path at the foot of the forest) and niz or nican (Spanish: aquí; English: here). Images of plants, architecture, and people, both Indigenous and European, abound in the iconography and language of these texts.

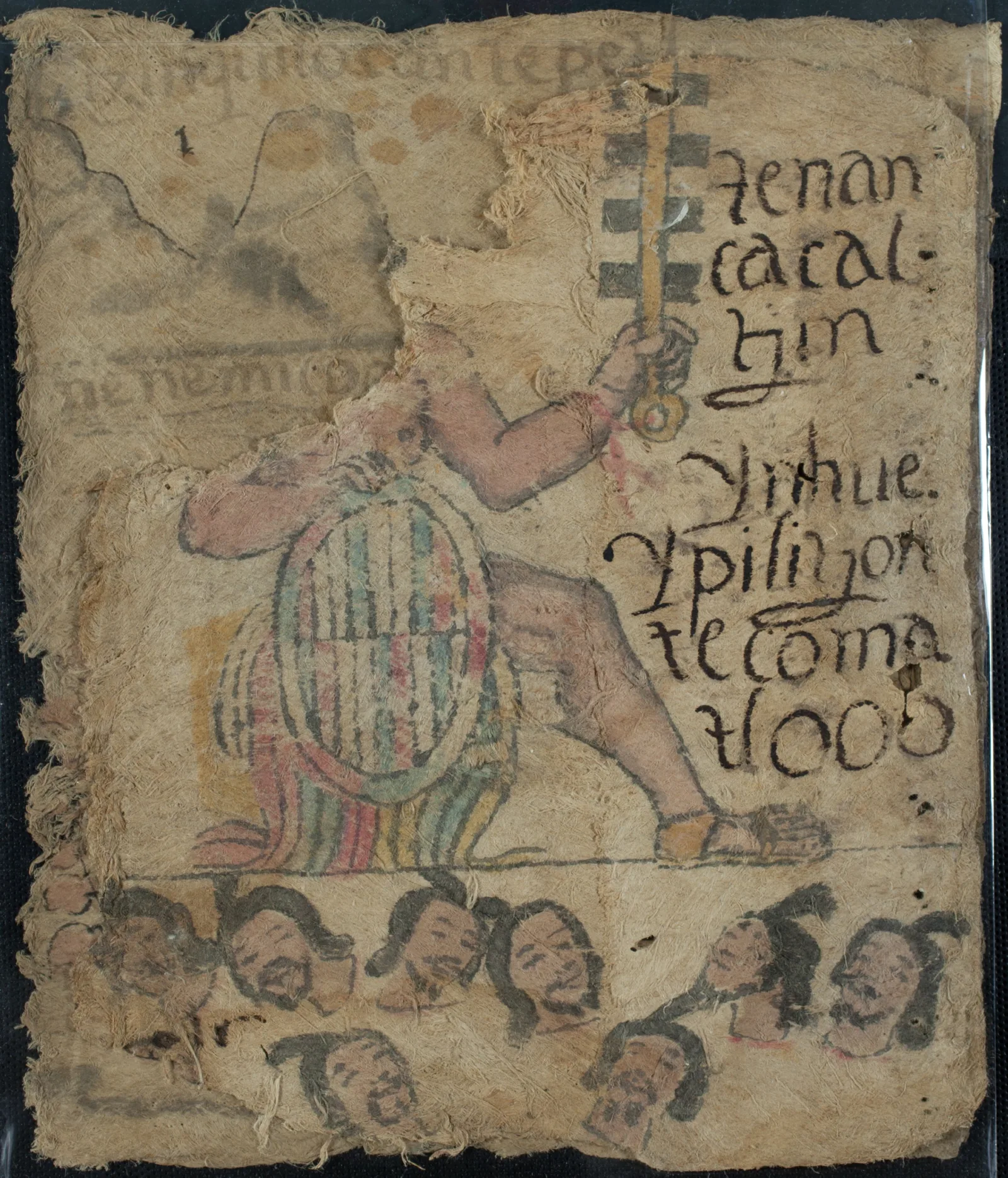

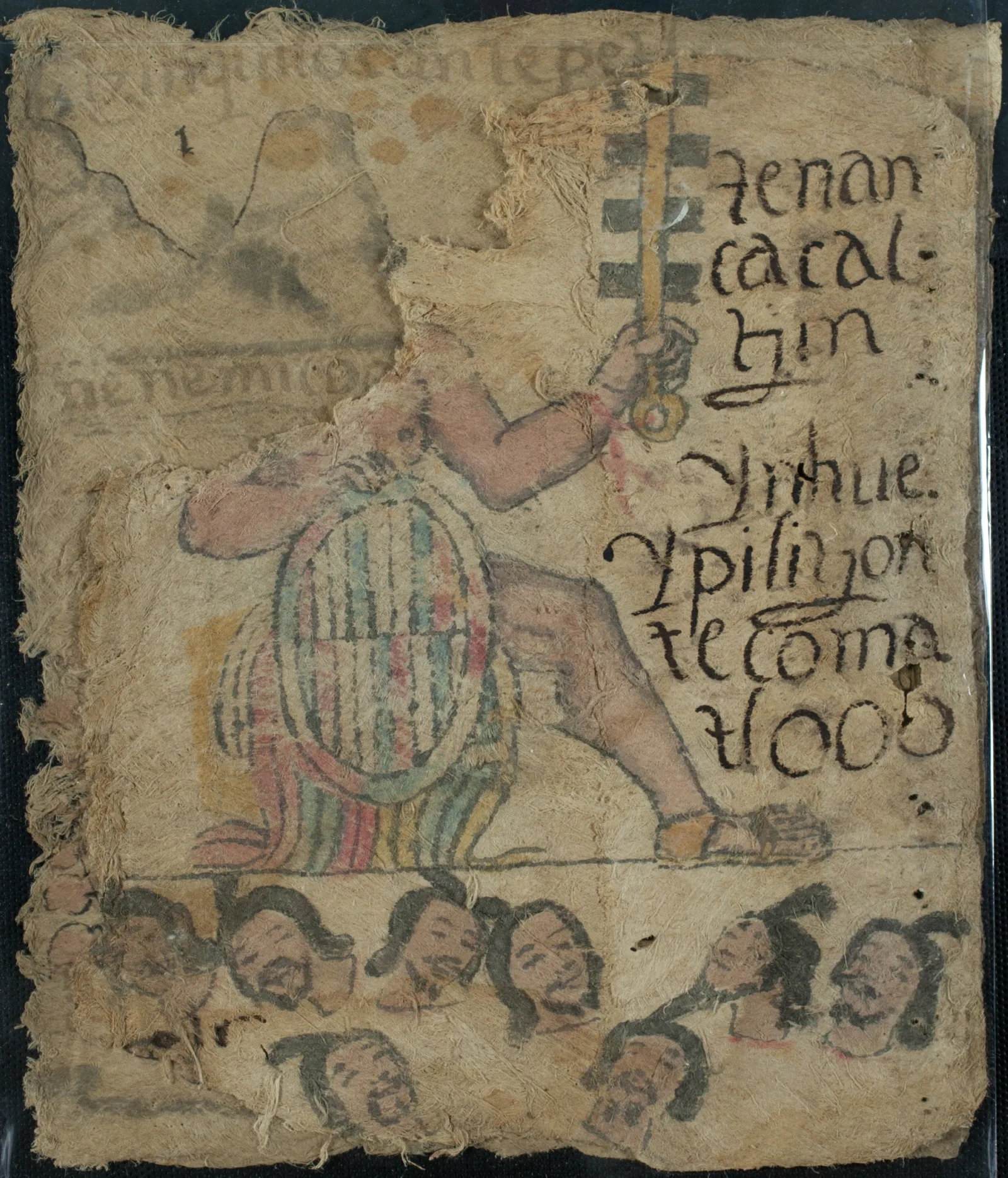

We also see a group of severed heads with closed eyes appear under a great lord called Tenancacaltzin Tzontecomatl, which may refer to warriors or a political head, in the case of the Techialoyan of Zempoala.

The name “Zempoala” translates from Nahuatl to mean the “Place of Twenty Waters.”

Note: The Newberry acquired the items in the library collection in good faith from what were believed to be their proper owners. Yet we also acknowledge the long history of removal of cultural heritage from Latin America, and particularly from Indigenous peoples, to colonizing nations and institutions. Such removals sometimes occurred through pillage, theft, coercion, exploitative purchase, and other inappropriate means. We recognize this historical context and seek to build reciprocal relationships with the communities from which these items and the knowledge they carry came.

Español

A finales del siglo XVII y principios del XVIII, los Pueblos Originarios de México afirmaron sus derechos a la tierra frente a la colonización española. En ese momento, los españoles estaban imponiendo su propio sistema de haciendas, ranchos y otros mecanismos para regular la tenencia de la tierra.

En respuesta a las políticas que amenazan la tierra, el agua y la autonomía de las comunidades indígenas, las comunidades desarrollaron documentos conocidos como Techialoyan. Estos documentos tenían como objetivo respaldar los reclamos de tierras indígenas en México al documentar la fundación y la historia de una ciudad, ilustrando los límites establecidos desde hace mucho tiempo antes de la llegada de los colonos españoles. Los Pueblos Originarios utilizaron los documentos como actas de sucesión para demostrar que la autonomía de sus pueblos deben ser respetada como cabeceras (distritos judiciales) en el sistema español.

En última instancia, los documentos tenían como objetivo salvaguardar y conservar las formas de vida de los Pueblos Originarios.

En total, hay unos cuarenta documentos Techialoyan que datan de los siglos XVII y XVIII. La mayoría utiliza el alfabeto latino, pero evita utilizar papel europeo; en cambio, están hechos de Amatl (papel de corteza de higo), un tipo de sustrato indígena. Un buen ejemplo de un Techialoyan es el manuscrito conocido como el Codex Zempoala, producido en algún momento de la primera mitad del siglo XVIII y alojado en Newberry en la colección de Estudios Indígenas y Nativo Americanos.

El pueblo Nahua de la ciudad de Zempoala en el estado de Hidalgo, México, hizo valer sus derechos a través de este documento, un libro que demuestra su relación de larga data con la tierra. Algunos académicos, como Stephanie Wood, han especulado que el documento, como otros de este tipo, fue diseñado para parecer más antiguo con el fin de validar aún más los reclamos de tierras establecidos desde hace mucho tiempo. Dado que no parece un códice típico, el Codex Zempoala a menudo se conoce como un “libro de tierras de aldea”.

La mayoría de los documentos de Techialoyan utilizan palabras y expresiones comunes en todas partes, a menudo repitiendo frases como Nenehmi coaxohtli (español: camino al pie del bosque; inglés: path at the foot of the forest) y niz o nican (español: aquí; inglés: here ). Imágenes de plantas, arquitectura y personas, tanto Indígenas como europeas, abundan en la iconografía y el lenguaje de estos textos.

También vemos aparecer un grupo de cabezas cortadas con los ojos cerrados bajo un gran señor llamado Tenancacaltzin Tzontecomatl, que puede referirse a guerreros o un jefe político, en el caso del Techialoyan de Zempoala.

El nombre “Zempoala” se traduce del náhuatl como el “Lugar de las Veinte Aguas.”

Newberry adquirió materiales de buena fe de los que se creía que eran sus verdaderos propietarios. Sin embargo, también reconocemos la larga historia de sustracción de patrimionio cultural de América Latina, y en particular de los pueblos Indígenas, por las naciones e instituciones colonizadoras. Estas adquisiciones se produjeron a veces mediante el saqueo, el robo, la coacción, la compra con fines de explotación, y otros medios impropios. Tomando en cuenta este contexto histórico, nos esforzamos por construir relaciones recíprocas con las comunidades de las que proceden estos objetos y los conocimientos relacinados con ellos.

Nahuatl

Okihkwilo Analú López, Amoxtlahpixke Masewaltlamachtilli.

Ka itlamian nin xihtlalpilli XVII wan ka ipewayan XVIII, inon Masewaltlalmeh Mexiko okihtokeh mowaxkatiskeh oksepa intlal tlen okinkwilikeh espanioltintlakah. Ihkwak, non espanioltlakah okinchitaya inkalwehweyin, otlaltsakwayah wan oksekin tlemach tlenon ika kwali mowaxkatiskeh inon tlalmeh.

Kine inon tlenon okichikeh ika inon tlenon okintlalkwilitayah, okinkwilitaya imawa wan non kenin iwalnentiwitseh masewaltlakah, inon masealtepemeh okinchihchikeh amameh non okinkwitikeh Techialoyan. Inin amameh itech owalnestaya keman omochihchi kanin chantih, okimixkopinayah kanin otlamiya intlal kiyon kenime oktaya kwak ayimo witsasih inon espanioltlakah. Inon maswaltepemech okinkwiyah amameh kenime aktatin non kampa walneste inon kenime ihwan iwalnentiwitseh ma kintlakaitilikan kiyon kenime tlayekantlalmeh ipan non kenime opekeh kintokayotiah non espanioltin.

Wan tla amo okintlakaitiliayah inin amameh okinkwiyah ompa kintlaliskeh kenin onemiyah iwehka masewaltepemeh.

Ika imochtin, onkateh kana ompowalli amameh Techialoyan non walewah pan xihtlalpilli XVII wan XVIII. Miyek itech inimeh kinkwih non latinotlahkilolli, maski amo kikwih eoropaamatl; kwe nikan, okinchihchiwayah amameh non ika okinchiwayah ikakawayo igokwawitl. Ika nin tlenon kwali titeititiskeh sente nin Techialoyan inon amatlahkwilolli inon kixmatih kenime Codex Zempoala (nikan ka se kopia), non okichihchikeh ka itlahkotian nin xihtlalpilli XVIII wan axkan paka Newberry itech inon amoxtlasentlalistli itoka colección de Estudios Indígenas y Nativo Americanos.

Inon altepenawa ipan sempowala ipan tlen axkan estado Hidalgo, Mexiko, ika omonawaltikeh nin amameh, kwe itech inin amatl walneste iwehka inwaxka nin tlalmeh. Sekin weyimomachtikeh, kenime Stephanie Wood, kihtowah inin amatl, kenime oksekin kenime inimeh, omochichikeh kwe okinekiyah ma nesikan kachi iwehka wan kine kiyon kwali kihtoskeh ihwan inwaxka nin iwehka tlalmeh. Kwe amo nesi kenime sente iwehka amoxtli, inin Sempowalamoxtli noihke keman kikwitiah kenime “amoxtlalaltepetl”.

Miyek nin amameh Techialoyan kinkwih tlahtolmeh sentetl mowiyan, wan miyekpa kimokpawiyah kenime Nenehmi coaxohtli (ika español: camino al pie del bosque; ika inglés: path at the foot of the forest) wan niz noso nican (ika español: aquí; inglés: here ). Tlaixkopinalximeh, kaltlachimeh wan tlakah, kenime masewaltlakah wan eorotlakah, miyek tlaixkpinalmeh wan tlahtolmeh itech inin amameh. Noihke kwali tikitaskeh walnesi tsontekomalmeh yokinkechtetekeh chikoptikateh itsintlan se weyi tlakatl itoka Tenancacaltzin Tzontecomatl, tele kenime non yaotlakah noso tlayekantlahtowani, kiyon kenime walneste itech inon Techialoyan Zempoala.

Inon tokaitl “Sempowala” tikasohkamatih kenime “kampa onkateh sempowalli atl”.

Nota: Inon Newberry okinko inin amameh ika kwali inyolo kiyon kenime otiknemiliayah akinomeh otikinkowilikeh. Maski, noihke tikmatih iwehka ikinwalkixtitiwitseh akin melawak inwaxkawan ipan mochi inin amerikatlalli, maski kachi ipan inon masewaltlalmeh. Miyek nin kenime ka okinkixtikeh nin amoxmeh san okinwikakeh, okimmichtekeh, otlakahkayakeh, noso otepanoltikeh kwak otekowiliayah wan okseki tlemach amo kwali. Tikitah nochi inin tlenon yopanok wan timochihchikawah timotelanaskeh inwan masealtlalmeh non kampa walewah mochi inin tlenon nikan tikimpiah wan mochi inon tlamatilli tlenon kimpia.

Okitlahtolkwep Victorino Torres Nava

About the Author

Analú López is the Ayer Indigenous Studies Librarian at the Newberry.