Chicago is, and always has been, an Indigenous place. As Potawatomi, Odawa, Ojibwe, Peoria, Kaskaskia, Myaamia, Wea, Thakiwaki, and Meskwaki homelands, along with several other nations whose homelands intersect with present-day northeast Illinois, the Chicago area has long been a historic crossroads for many Indigenous peoples and continues to be home to an extensive urban Native community.

Recognizing this long history of Chicago as an Indigenous space, members of the Newberry Library, Carleton College, the Chicago American Indian Community Collaborative (CAICC), and the Chicago Native community have embarked on a multi-year project known as Indigenous Chicago. Supported by a generous grants from The Mellon Foundation, the Whiting Foundation, the Terra Foundation, the Driehaus Foundation, and the Research for Indigenous Social Action and Equity (RISE) Center at the University of Michigan, the project aims to explore the city’s Native histories in a public history context, all while centering Indigenous voices, laying bare stories of settler-colonial harm, and gesturing toward Indigenous futures.

Since 2020, the Indigenous Chicago team has been hosting listening sessions to ensure that Native community members are involved in the brainstorming, development, and execution of the project. In 2024, there will be an exhibition at the Newberry, a website with an interactive mapping component, curricular materials for K-12 students, new oral histories, scholarly and public programming, and more.

“Native peoples and communities are the best representatives of their own histories and cultures, and our partners will lead the way as we identify new opportunities to deepen our relationships with Indigenous nations, support Native-led research, and remove structural barriers to collections held at the Newberry,” said Rose Miron, Director of the Newberry’s D’Arcy McNickle Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies.

Meredith McCoy (Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa descent) has been working with Miron and the rest of the Indigenous Chicago team to plan the curricular materials that will be used to help K-12 teachers teach Native history to their students. McCoy is an Assistant Professor of American Studies and History at Carleton College. Her research focuses on how Indigenous people have long repurposed tools of settler colonial violence to promote their rights and preserve their cultures. As a Frances C. Allen Fellow at the Newberry in 2018, McCoy utilized archival materials related to the federal government's program to relocate Native people from reservations to American cities in the mid-20th century. From there, McCoy’s involvement with the Indigenous Chicago project began.

The Newberry Magazine recently interviewed Meredith McCoy about her work and involvement with the Indigenous Chicago project. The interview has been edited for clarity.

Can you tell us a little bit more about yourself, your background, and the work that you do now?

Meredith McCoy: I’m a professor of Indigenous Studies at Carleton College, where my official title is Assistant Professor of American Studies and History.

My research is mostly about histories of federal policies for Native students, the histories of education, and how Native families and communities and students have repurposed policies that were intended for their assimilation or destruction into tools that can actually be used towards Indigenous life. My work thinks about how we as Native people often find ourselves in these constraints of settler systems, but despite that, we've always navigated those spaces strategically and planned for a future that we will be in.

I'm also a former middle school teacher—I’m a teacher at heart. I see another part of my work as translating research that’s happening in history spaces into examples that are accessible to K-12 teachers.

Maybe the best part of my job is the work that I get to do with students at Carleton. I teach courses about the ethics of research partnerships with Native people, about histories of Indigenous activism, histories of education for Native students, as well as a course that allows students to get into the Carleton archives and learn about the history of Carleton as an Indigenous space.

The Indigenous Chicago project that I work on with Rose, Analú Lopez (Guachichil/Xi'úi, Ayer Indigenous Studies Librarian), Sarah Jimenez (M’Chigeeng First Nation, D’Arcy McNickle Program Coordinator), and Blaire Morseau (Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Nation, consultant for the McNickle Center) fits into my work as part of my second book project. In 2018, I was still a grad student, and I was a fellow at the Newberry on a fellowship for Native women. With the support of Analú and the Newberry’s Ayer Collection, I researched relocation [of Native people to American cities under a program run by the federal government] and what that was like for my tribal community. My dad is a citizen of the Turtle Mountain band of Chippewa Indians in North Dakota. That research grew into this longer partnership and my participation in the Indigenous Chicago Project.

The Indigenous Chicago project involves so many people and groups, including Carleton College, the Newberry Library, Chicago American Indian Community Collaborative (CAICC), and members of the Chicago Native community. Can you tell us more about the collaborative nature of this project? Why is this important?

Really, Rose, Analú, Sarah, Blaire, and I didn’t decide that we wanted to pursue the project. Rather, we decided that we wanted to ask the community if they wanted us to pursue it. For us as folks who do work in Indigenous Studies spaces, it felt like a really important ethical choice given the long history of researchers deciding what they’re going to do for Native communities and not asking them.

Before we even started this project, we held a big community meal. Indigenous communities gather over food. We got everybody together, worked with an Indigenous caterer from this area, fed everybody, and just talked about the possibilities for this project. The very first question we posed was, “would a project that traces the long history of Chicago as an Indigenous space—one that might have components of school materials, museum exhibits, digital mapping, oral histories—be of utility to the Chicago Native community?” All we were looking for in that first meeting was a “yes” or “no.”

What we heard from the community was “yes.” From there, we asked folks who had been at that meeting and other community members if they could recommend anyone that they thought should be on the advisory board to make sure we go about this in a good way.

We ended up with a list of about 30 people who agreed to be on the advisory board. We eventually had a hybrid (in-person and virtual) convening with our advisory board members, and in that meeting, we profiled the different possible components and subcommittees within the larger project, like curricular resources, oral histories, and more. We're now at a place where each of the subcommittees is meeting on their schedule based on their specific needs and what we're trying to create.

It was important to us that our advisory board members be compensated in a way that felt ethical and honorable, so we’ve been able to apply for several external grants to support this work.

It was important to us as we built out the advisory board that we reached out to folks who identify Chicago as their home, whether they’re part of the urban intertribal community that Chicago is known for now, or whether they're from Native nations whose homelands are what we now understand as Chicago. We’ve been in communication with and have representatives of multiple Native communities who claim Chicago as their space.

Why is it important to expand the public's understanding of Chicago's Indigenous past and present?

87% of school curricula only talk about Native people prior to the year 1900. Until this past year, Illinois was one of the states whose standards had no mention of Native people at all. The state has recently undergone some standards revisions, but that’s very recent. There’s a significant problem nationwide with Indigenous erasure.

Stephanie Fryberg is a Tulalip researcher, and she said that invisibility is the modern form of racism against Native people. When we were having conversations with the Chicago Native community, that issue of people feeling like they're not seen came up, like they're not reflected. Part of what we're trying to do with the Indigenous Chicago project is increase the visibility of the Chicago Native community in a way that is reflective of how they see themselves.

Of course, that has implications for all kinds of things. We know the kinds of racism that results from the invisibility of Native people, when they’re not seen as modern thriving people. It has implications for what programs and communities get funded. There are lots of things that this is going to have implications for, and we think it's really critical that as the issue of Native visibility becomes a national issue, it also gains traction in Chicago.

Also, Chicago is a location where you've got a Native mascot issue. Increasing people's understanding of Native people as not caricatures is important in a local context, too.

Part of this educational effort involves an aspect of truth telling around the roles that the U.S. and institutions have played in perpetuating settler colonial violence. How do you plan to do this or enact this truth-telling aspect in your involvement with the project?

I think curriculum is a powerful vehicle for telling the truth. Young children are infinitely more capable of handling nuance and difficult content than we usually give them credit for. Young people also have such a clear sense of justice for what is and is not fair. When we're thinking about telling these hard histories in a way that is accessible to young people, we can think about things like reading levels, writing levels, and the kind of vocabulary that we use, but we also need to trust that they can handle the content.

As we're developing these curricular resources, we’re looking to the Chicago Native community to identify the topics and the resources that they would like us to focus on and teachers to be talking about. We also know that part of that involves supporting teachers and building their sense of confidence in approaching this content in their classrooms. So, truth-telling is both speaking directly to the kids through the materials and speaking to the teachers.

What we want to do is make sure that teachers feel confident, supported, and clear in their own understanding of the material, so that they can deliver this content with their students in a way that feels like they're able to support them. This work is never done in isolation. We’re always in a community of parents, students, teachers, school administrators, faculty—all working together to make sure this is done in a good way. That’s when education is at its best.

The other constituency that I mentioned is families. Part of this project is helping families understand why truth-telling is important and valuable for their kids, and it does our children a disservice when we don't allow them to know the full truth of the place that they live.

How do you think this project will change the relationship that we have with the city of Chicago? How will learning about this history, seeing this history in a new way, and seeing Chicago as an Indigenous place change our relationship with the city?

There are going to be so many ways for people who are in Chicago (and beyond, since there’ll be digital components as well) to engage with this project. It’s incredible to me how shocked many people are when they learn that Native people are still here.

Once people do know that we're here, they then need to start thinking about some really important issues. They need to start thinking about tribal sovereignty and how they, in their daily lives and the structures around them, might see where tribal sovereignty is being exercised. It's important for people to see that our governments in our Native nations and our organizing structures in our urban spaces are actively promoting Indigenous autonomy—whether that’s through food sovereignty, reclaiming lands, or creating educational spaces that are culturally sustaining for our youth. It's important that people see us as contemporary and capable. Also, Indigenous models of governance and education are good for everyone.

Thinking about how this project might shift the general public's understanding of Native people, I hope they understand that what we are articulating and fighting for is a future for all our communities. What is good for us is good for everyone.

“ It's important for people to see that our governments in our Native nations and our organizing structures in our urban spaces are actively promoting Indigenous autonomy—whether that’s through food sovereignty, reclaiming lands, or creating educational spaces that are culturally sustaining for our youth.”

Meredith McCoy

You mentioned earlier that you were a Newberry fellow from 2018-2019. Are there any connections from that fellowship that you’re making in your work today?

The fellowship I had was the Frances C. Allen Fellowship. The Newberry has such a remarkable reputation when it comes to Native studies. When I was late in grad school and thinking about what came next, I kept getting this advice from mentors: you need to see how your work might be enriched by spending some time in the Newberry.

When it came to independent libraries and national repositories, I wanted to look at records from my nation, Turtle Mountain. That was the initial connection point for me. Once I got into the archives and the relocation files specifically, one of the things that I noticed was that you absolutely do see evidence of federal coercion, you see evidence of the bureaucratic violence of convincing people to relocate and then not adequately supporting them. I also noticed how many times schools were mentioned in those kinds of government records, which reinforced for me this idea that relocation was not just about economics—it was also about parents trying to figure out what to do to support their children against a history of economic deprivation in our reservation communities.

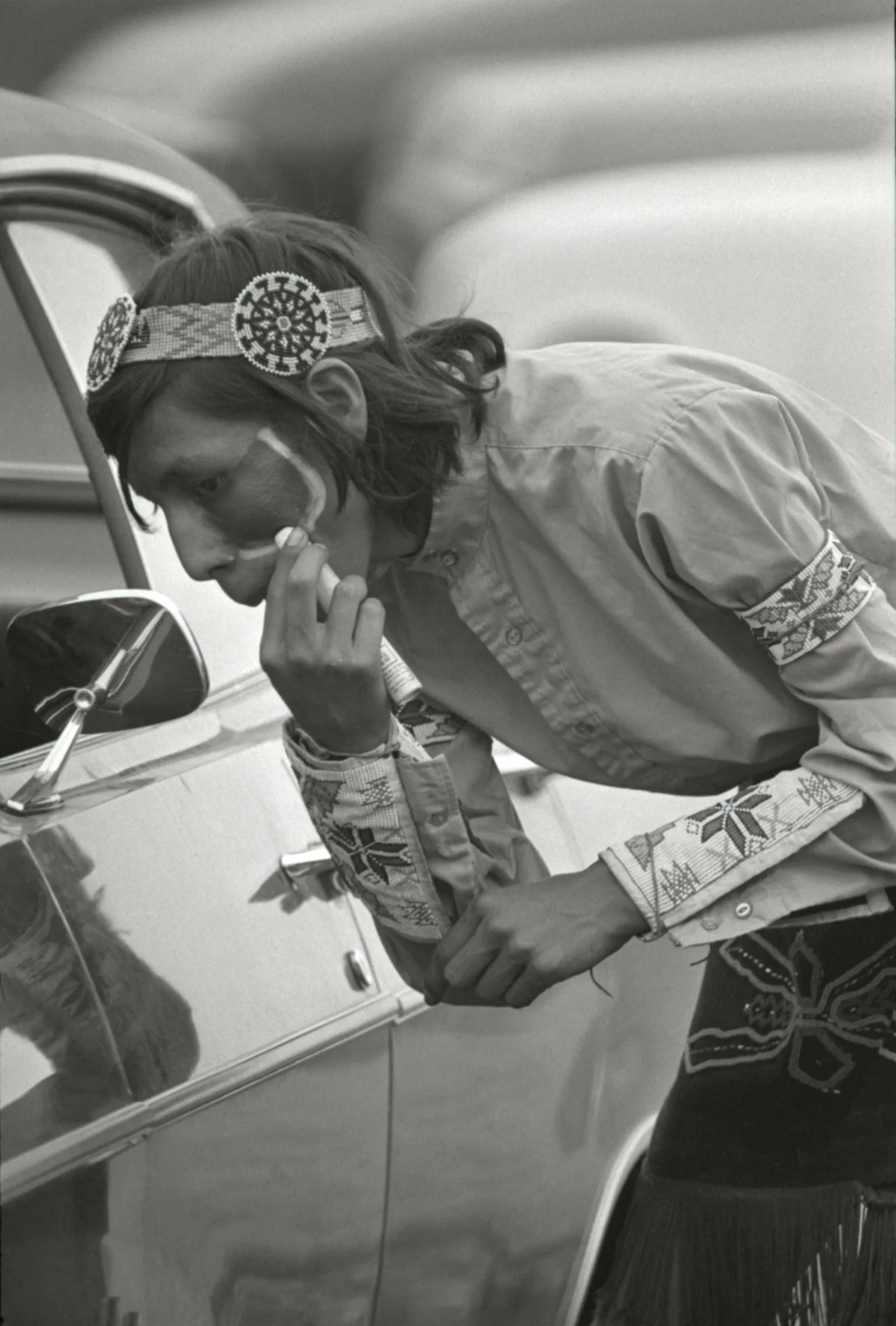

In these materials, you also see examples of Native joy that pop out of these places where you don't necessarily expect to find them. We've been highlighting some of these materials through the Newberry 101s [monthly “lunch and learn” virtual sessions that feature an item from the Ayer collection related to the Indigenous Chicago project]. Some of the things we've been looking at are very colonial, like settler-made maps for example, but we've also got things like Powwow flyers from the 1970s, or relocation scrapbooks.

These scrapbooks in particular are sources that we have to read carefully, since these are often posed photographs that were taken for the purposes of convincing other Native people to relocate.

As Native historians and historians of Native studies, we’re doing this work of “reading between the lines” to find those moments of Native strategy and Native joy in the archive. One of the things that I hope comes out of the Indigenous Chicago project is the fact that “we are still here” does not just mean “we are still alive.” It means we are still a community, we are still joyful people, and we have always used laughter to sustain ourselves and to make sense of and cope with colonial violence. I’m hoping that thread of joy comes through in the work that we’re doing, and that when people see us through this project, they get a sense of the history and a sense of our creative resilience.

How do you stay motivated in this work?

It's all about community, all the time. As one of the researchers on the team, that sense of who I’m accountable to is a really strong motivating and sustaining factor. If I don't do this well, there are ramifications for the community. It’s going to fall on the community just as much as it will on me. I do feel a sense of energy and sustenance by knowing who I'm responsible to in this work. I also feel that we get our energy by being around each other and in community—we feed each other both literally and metaphorically.

Also, going off what I just mentioned about joy—the idea that laughter is medicine resonates so palpably with me. When you get a whole bunch of us together, it doesn't take long before we're all giggling. I was just at an education convening in Kansas, and Comanche scholar Cornel Pewewardy was there. He said to us, “When you’re doing this kind of work, you need to think about where your medicine is coming from, where your power is coming from. Where is your medicine and power coming from to do this work?” For me, that’s my community.