During the 2023-2024 academic year, a group of Newberry fellows and scholars-in-residence from different fields and disciplines in early modern Iberian studies developed a common interest in a methodological approach called “the rhizome,” which embraces the vast array of complicated connections between ideas, objects, and actions in the past, just like the complex root systems of subterranean plants that originally carried that name. The so-called Newberry Rhizome Group explored this interest through informal conversations, research in the reading rooms, and at CRS programming throughout the year. This post is Part Two of a series in which these scholars share the fruit of these explorations. To see Part One, click here; for Part Three, click here.

This collection of contributions was designed and edited by Fabien Montcher (The Saint Louis University Center for Iberian Historical Studies - CIHS) and Maria Vittoria Spissu (Marie Skłodowska-Curie Global Fellow - University of Bologna/The Newberry Library) in the Spring and Summer of 2024.

Claire Gilbert, Department of History, Saint Louis University

Lexicography as Rhizome

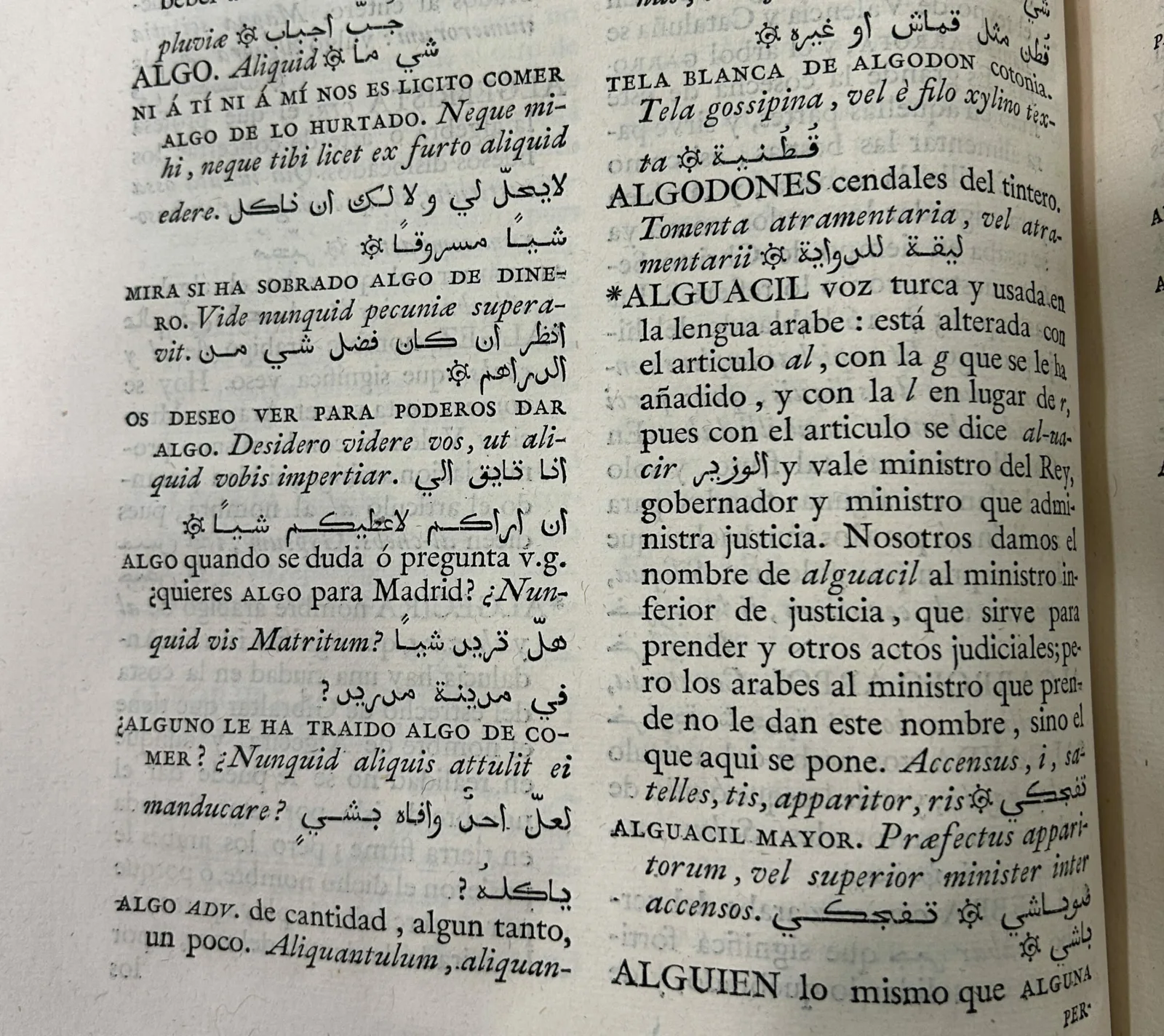

The 1787 Diccionario Español-Latino-Arábigo of Francisco Cañes (1730–1795) represents a signal undertaking in the history of Iberian Arabic linguistics. Published in Madrid in 3 folio volumes, the Diccionario used typographic and chalcographic innovations while invoking a longer tradition of Renaissance linguistics.

Alongside grammars and explicitly ideological discourses–like dedications and other paratexts–lexicography created opportunities to express linguistic normativity. Nevertheless, their rhizomatic nature allows dictionaries to subvert linguistic normativity imposed by ordering (e.g., alphabetic), definitions, and examples. In the Cañes dictionary, intertextuality and cross-referencing create the possibilities for rhizomatic reading. The user follows the path dictated by their own interests.

Rhizomatic subversion, however, does not obviate ideological expressions represented in lexicography. In entries like ALMADRABA (tuna fishery) or ALGUACIL (government official), Cañes reflects on different languages and usage communities in conjunction with politics, gleaned from his experiences in the Ottoman Empire or working with Andalusi texts. Indeed, ideology emerges as its own rhizome; manifesting in predictable and unpredictable ways, without a central node or single genus.

A rhizomatic approach to lexicography reveals the entanglement of linguistic traditions and non-linguistic aspects of knowledge and communication (e.g. social relations encoded in paratexts, technological innovations encoded in the physical aspect of books).

Lexicography–like grammar–was a genre meant to help distinguish one language from another and thus buttress political claims and cultural distinctions. The resistance inherent in the rhizome does not negate the harmful use of missionary and colonial linguistic works in imperial settings where language was both a proxy and a motive for violence.

View the catalog entryMiguel Martínez, Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, University of Chicago

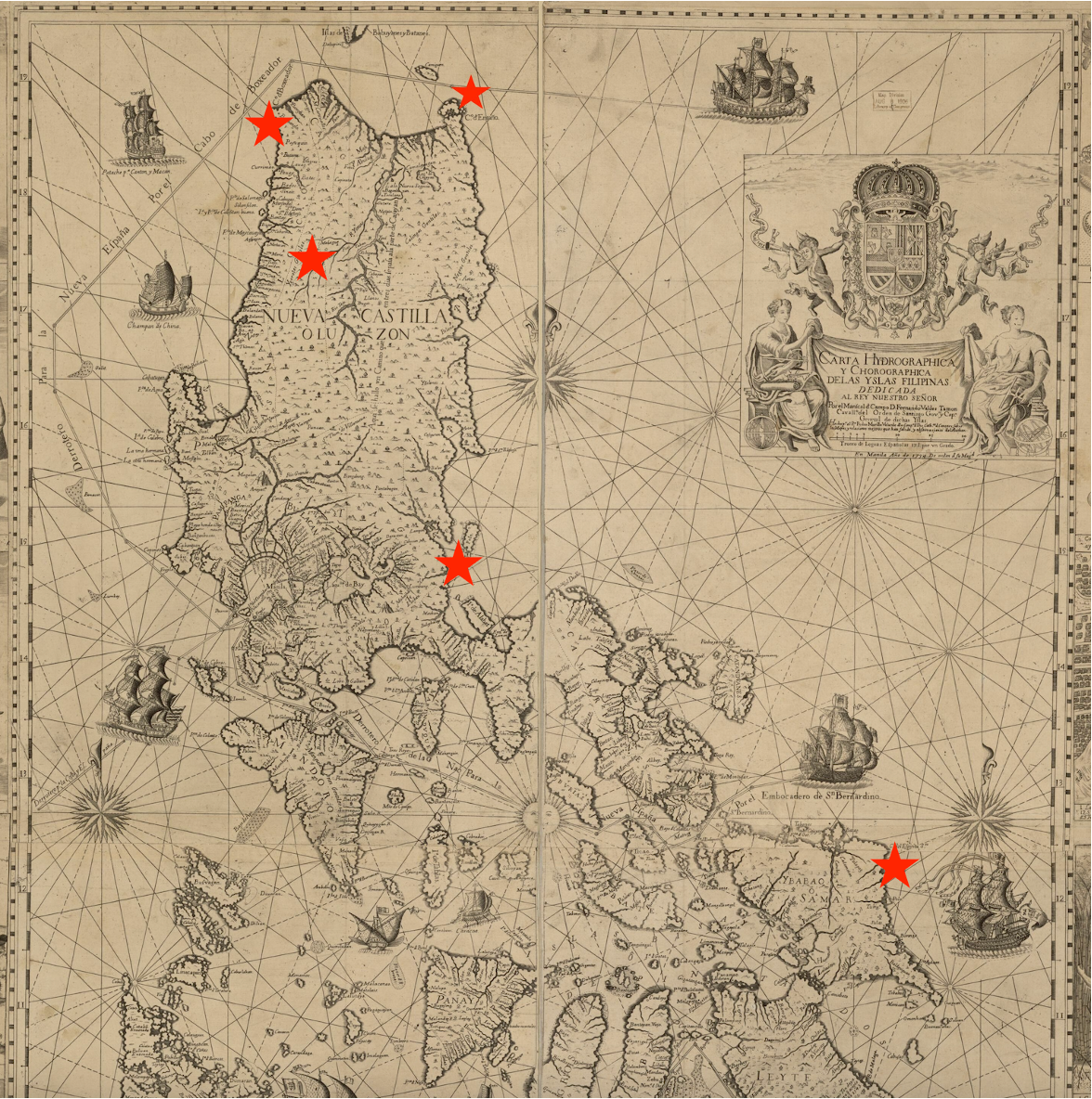

Against Depth. On Shipwreck in the Spanish Pacific

Early modern shipwreck narratives can be found in unexpected places. This rather dry judicial document, which deals with the inheritance and estate of rich merchant and encomendero Esteban Rodríguez de Figueroa, contains a lively story about the shipwreck of the San Antonio de Padua galleon in 1604, off the eastern coast of Luzon, in the Philippines.

In the aftermath of the dramatic sinking, broken crates containing Chinese silk garments, hats, ivory, and wax washed up in remote beaches. The few survivors tried to find their way to distant shores. For months, tidal forces kept pushing to the surface and scattering the galleon’s cargo.

Shipwreck disperses wares, capital, and people. It deterritorializes and reterritorializes, to use Deleuze and Guattari’s language. In this case, it interrupted the linearity and verticality of the Manila galleon, in favor of horizontality. The accountants of the king were incapable of tracing the property washed ashore back to its owners. But the commodities, which are not commodities any longer, found new unexpected owners. As if following Deleuze and Guattari’s “first principle of connection and heterogeneity,” according to which, “any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other,” shipwreck puts in touch the surviving Spanish merchants and aristocrats on their way to Mexico with the sovereign Itneg people of Cordillera, and brings Chinese taffeta to parts of the Philippines that had no part in the transpacific trade. It plants commodities and people in new plots.

Shipwreck causes rerouting and rerooting, so to speak, imposing randomized detours on the circulation material objects of diverse origin and multiplying their uses. If a rhizome is a “subterranean stem,” we could think of the intricate entanglement between subaquatic currents and history.

Fabien Montcher, Department of History, Saint Louis University

Indigenous 'Libertins,' French 'Naturales,' and African 'Dévots,' in 'La Martinique' (c. 1640)

Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizome is best contextualized within a constellation of works that draws the focus to zones of engagement where fluid combinations between hegemonic and alleged “societies without chiefs” happened:

Pierre Clastres, Society Against the State (1974)

Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (1990)

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Politique des multiplicités (2019)

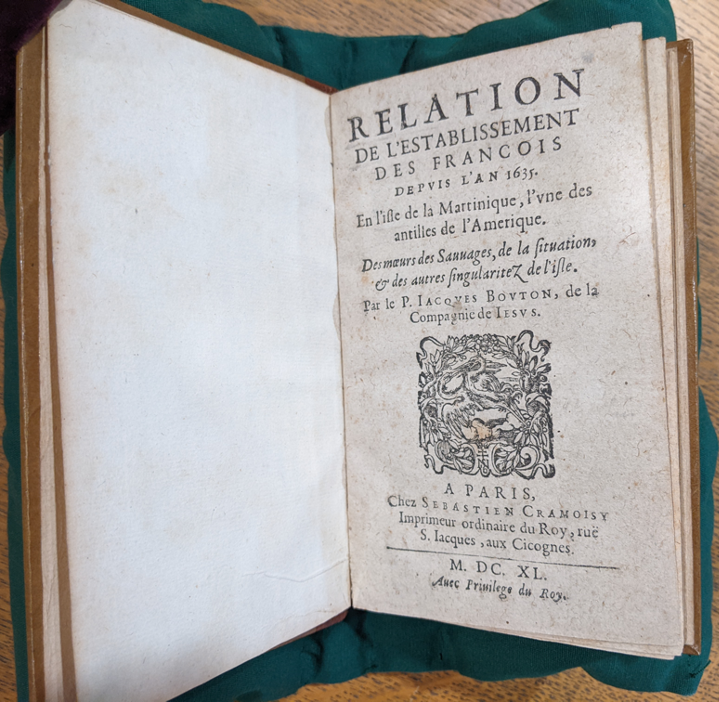

In his 1640 Relation de l’establissement des François en l’isle de la Martinique, the Jesuit Jacques Bouton registers the transformation of La Martinique into an eco-agricultural hub. He presents a sleek picture of the French colonization of the island by erasing references to Iberian conquests and underlining the weak authority of Carib “captains” (chiefs).

Bouton’s lightning but repetitive allusions to ceremonies of gender inversions among Caribs, conversations between fishermen and turtles, and enslaved African “dévots,” all complicate the 1630 arrival of a thousand French colonizers on the island. In his colonial survey, adjectives such as skeptics, weak captains, or dévots coalesce. All these discreet protagonists end up sharing the same “wild fruits, roots, and all sorts of animals”.

How could these political, bodily, and philosophical entanglements inspire the writing a post-global history made of singularities trapped in webs of relation and tied to the violent fabric of pre-modern capitalism? The rhizomatic analysis intensifies the reading of alleged side stories among a multitude of beings, temporalities, and spaces that goes beyond the grand narrative of an age of empires/encounters. It calls for a non-exclusive history of Iberian representational/social landscapes made of improbable entanglements.