All maps–from the hand-drawn documents created centuries ago to the app in your smartphone–reflect the culture, perspective, and knowledge of the people who formed them. One of the most important concepts that can be tracked through maps is movement. The movement of humans and goods throughout history illuminates the economic, political, and social priorities of society.

The Newberry Library’s Hermon Dunlap Smith Center for the History of Cartography embarked on the mammoth task of analyzing hundreds of American “maps of movement,” creating Mapping Movement in American History and Culture in 2016 with the support of a crucial grant from the Preservation and Access Division of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Unfortunately, the website host ultimately went offline, creating both the necessity–and the opportunity–of rebuilding Mapping Movement (mappingmovement.newberry.org) from the ground up. The new site flows naturally between image and text, maps revealing themselves to the reader as they scroll. There are links to each map for closer study, comparison, and download. The new Mapping Movement breathes fresh life into the meticulously crafted essays with dynamic design.

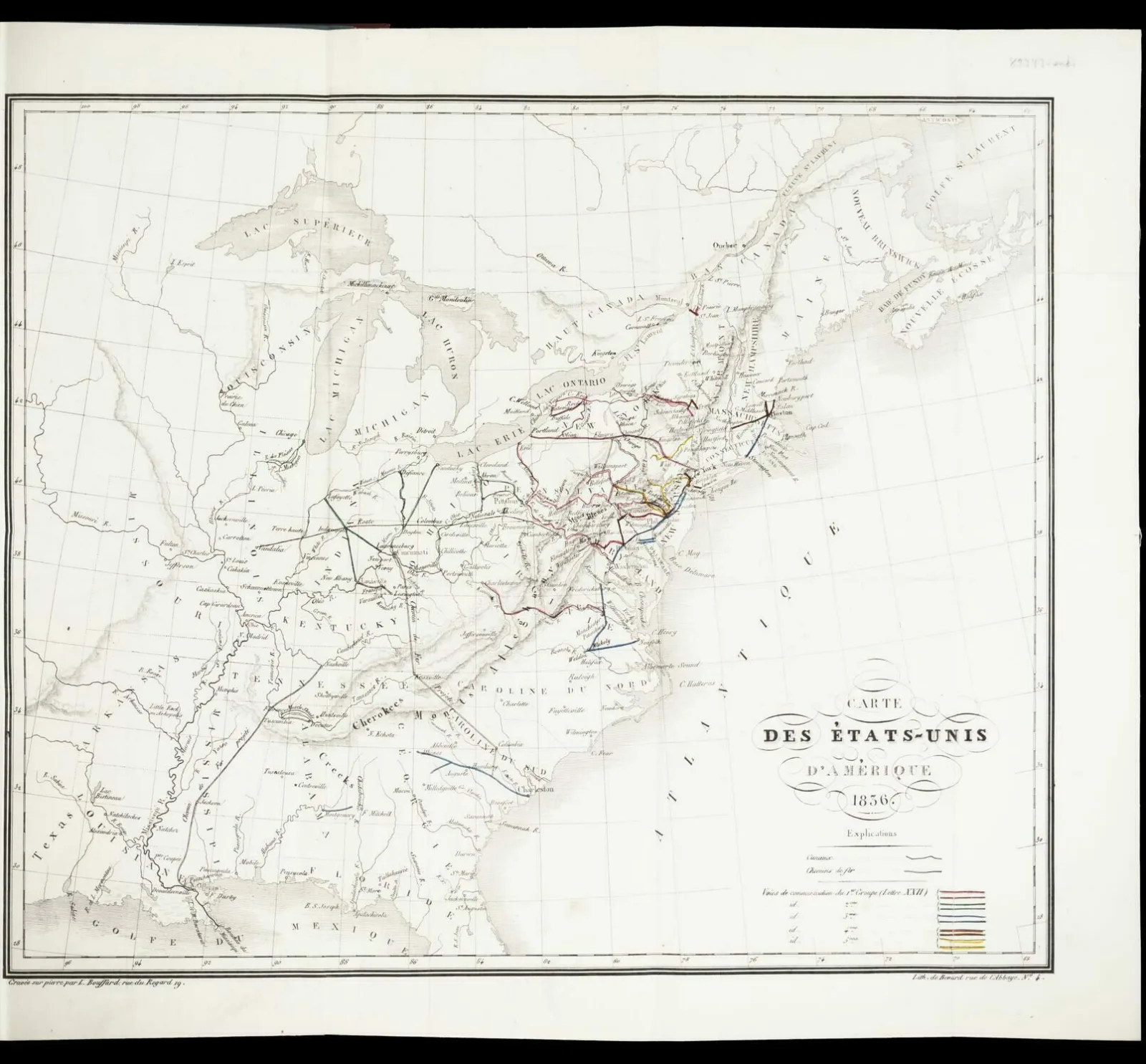

These essays–which span centuries of the Newberry’s map collection–cover fifteen essential areas of map history, from railroads to literature. They not only describe the world as it was, but also depict what people of the past wanted the world to be. For example, the French Ministry of Public Works sent Michel Chevalier to survey a potential national railroad network in the United States. He produced an 1836 map that expanded on the existing lines of the time, envisioning an interconnected future where “distance will be annihilated, and this colossus, ten times greater than France, will preserve its unity without an effort.”

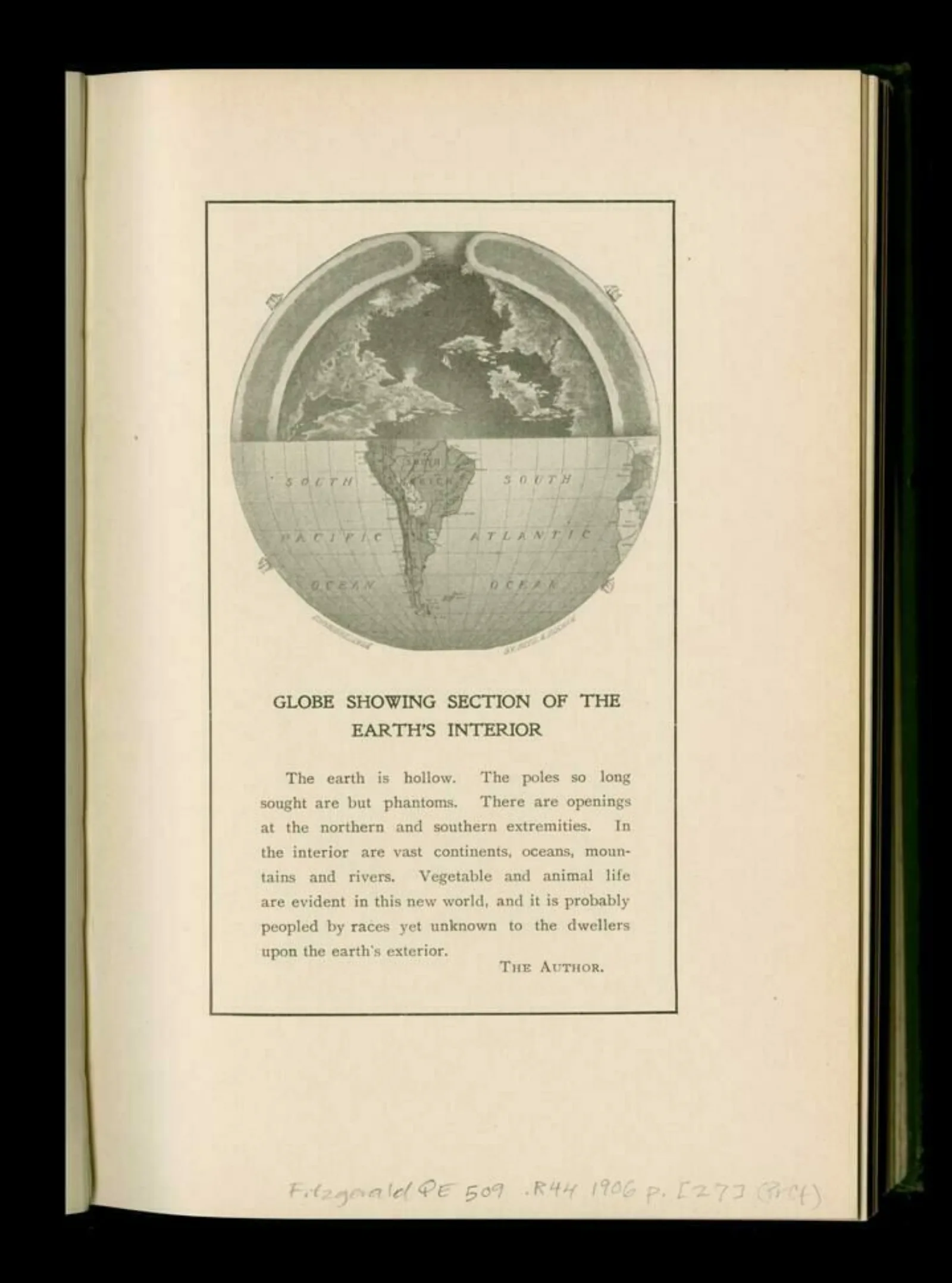

Some maps leave the real world behind entirely. William Reed’s 1906 book The Phantom of the Poles interpreted the observations of recent polar explorers into a vision of a hollow Earth. While further polar expeditions quickly debunked this pseudo-scientific concept, his map continued to inspire science fiction writers.

“With extensively researched articles by leading scholars, a carefully curated set of maps designed for use and re-use, and an interface that highlights the beauty and intrigue of these maps, Mapping Movement is an unparalleled resource for learning about how Europeans and Euro-Americans used maps to navigate (and imagine navigating) the world around them,” remarked David Weimer, the Director of the Smith Center and the Robert A. Holland Curator of Maps. The Newberry is pleased to bring this newly invigorated project back for scholars, classrooms, and all who seek to better understand our history.

Learn more about the website redesignAbout the Author

Quinn Sluzenski is the Digital Initiatives Assistant at the Newberry.