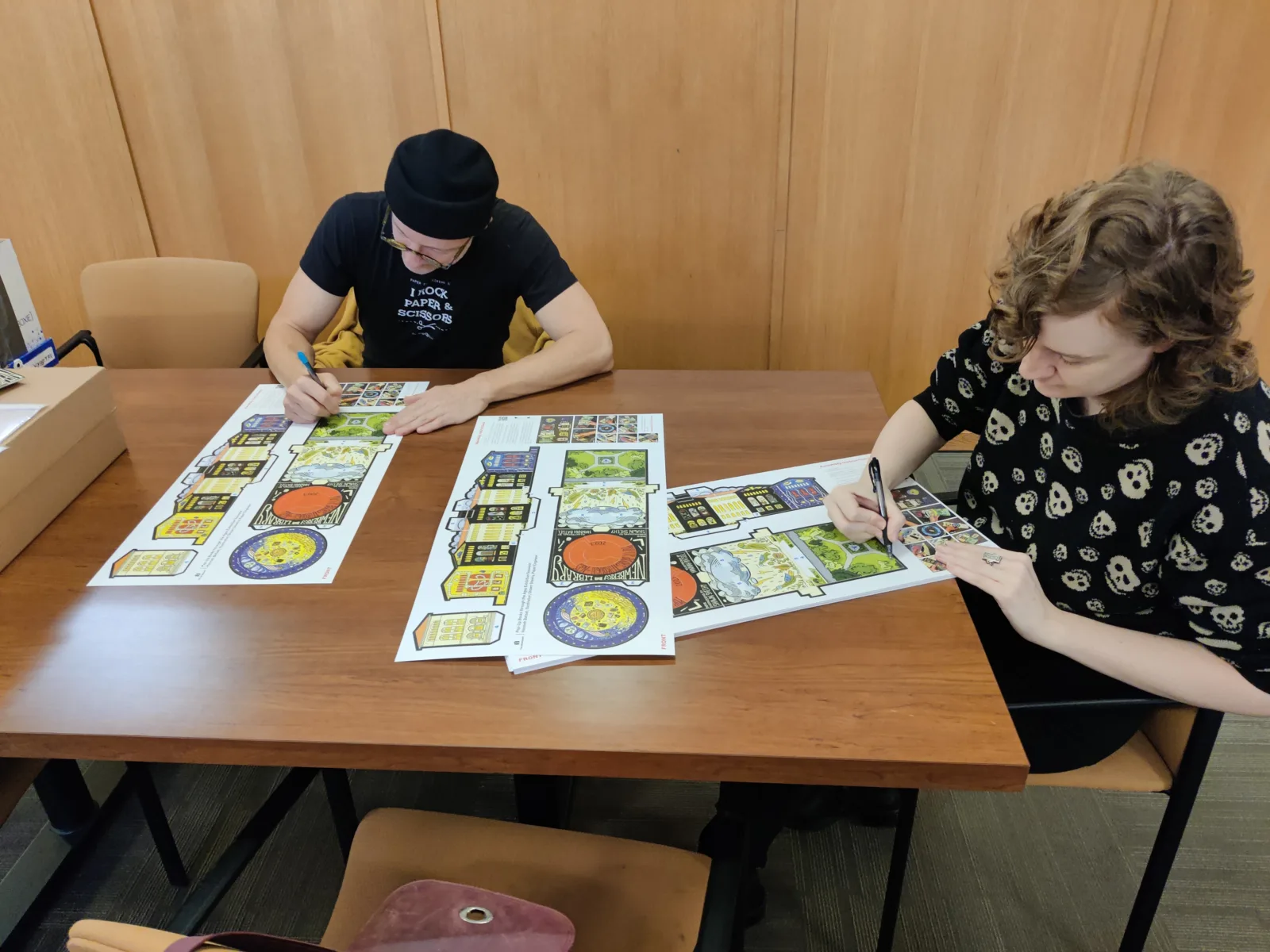

This past semester, the pop-up Newberry--a paper rendition of the iconic building--made an unexpected trip. They left Chicago and traveled across the country to a Connecticut prison, where I was teaching an undergraduate course on the history of the Scientific Revolution (c. 1500-1700) to a group of incarcerated women enrolled in college degrees through the Yale Prison Education Initiative and its partnership with the University of New Haven. One of the goals of this course was to move beyond studying famous figures like Isaac Newton and Galileo in order to explore the complex and diverse network of scientific practitioners who were active during this period. Historians like Pamela Smith and Pamela Long have beautifully shown that artisans were studying nature and running experiments, placing them among those “doing science” in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe.

But artisans were also involved in another key aspect of the Scientific Revolution: They were making books. Some of these books boast movable parts, like Peter Apian’s Astronomicum Caesareum (1540), which was recently featured in the Newberry’s exhibition Pop-Up Books through the Ages. The movable components of books like Apian’s could be used to perform complicated, mathematical calculations. But in order for these paper instruments to function, they had to be properly assembled. This was no easy task, particularly in the case of movable books like Johann Remmelin’s Catoptrum microcosmicum (1619), which contains over 100 moving parts. Publishing Remmelin’s text would have required a significant investment of artisanal labor.

I wanted my students to appreciate artisans’ role in the spread of science, and movable books provide an exciting entry point into thinking about their meticulous and time-consuming efforts. However, it is difficult to really communicate the work involved in publishing a movable book from images alone. I was eager to see what kind of lessons we would learn if we attempted a part of this process ourselves.

I was not disappointed. The "pop-up Newberry" allowed my students to simulate the kind of delicate assembly needed to produce books during the Scientific Revolution. This also led us to better understand why artisans worked the way they did. For example, as my students were incarcerated, we did not have any access to electronics. As a result, we were not able to benefit from the Newberry’s instructional video that starred disembodied hands deftly demonstrating how to build the pop-up library. Instead, we had to rely on written instructions. This was very challenging, even for a pop-up that was quite simplified when compared to those found in Apian or Remmelin. But our struggle to construct our miniature libraries also prompted further reflection in our class discussion.

We were experiencing firsthand why sixteenth- and seventeenth-century artisans were educated through apprenticeship rather than the university study that we usually associate with science. They needed to be trained by doing rather than reading. Reading was simply not sufficient for this type of work! Building our own pop-ups gave us a new understanding of this history. The Newberry brought the concrete realities of the world of the artisan into our unconventional classroom.

Visit the Newberry Bookshop online to purchase your own "pop-up Newberry."About the Author

Alicia Petersen is a PhD Candidate in the History of Science and Medicine Program at Yale University, and an instructor in the Yale Prison Education Initiative.

To learn more about the Yale Prison Education Initiative, visit www.yaleprisoneducationinitiative.org