The Chicago Pride Parade—held annually on the last Sunday in June—wasn’t always the massive street festival and celebration it is today. The first parades, organized in the early 1970s, drew a few hundred people, and the focus was overtly political. There to document it all was Eunice Hundseth Militante.

A photographer and an activist, Militante was a fixture at women’s marches, demonstrations, and Pride Parades in Chicago throughout the 70s, becoming a sort of unofficial photographer of the gay rights and feminist movements.

Her photographs are part of the Eunice Hundseth Militante Photograph Collection, a large archive of materials associated with Militante just acquired by the Newberry. The collection includes photographs documenting Pride Parades of the 70s, as well as informal photographs of life among women in the lesbian and feminist communities in Chicago.

The first Pride marches were inspired by the Stonewall riots in New York City—a series of protests by the city’s gay community against the storming by police of the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in Greenwich Village, on June 28, 1969. The following year, marches were scheduled to coincide with the anniversary of Stonewall in New York City, San Francisco, LA, and Chicago, where the march began in Bughouse Square, directly across from the Newberry. Organized by Chicago Gay Liberation and attended by around 150 people in total, the Chicago march passed through the Michigan Avenue shopping district before arriving at Daley Plaza, with marchers listening to speeches, dancing, and chanting slogans along the way.

Over the next decade, the Chicago parades grew and grew, attracting participants like Militante.

Born in 1942, Eunice Hundseth arrived in Chicago in 1960, studying art and honing her talent as a photographer before marrying Vincente Militante and taking a job at Evanston Hospital. By the late 60s, however, she had discovered Second Wave Feminism and become a self-described “raging full-blown feminist lesbian,” devoting herself to political action—and documenting her participation with her camera.

Militante’s photos offer a fascinating glimpse of the early days of Pride. In many cases, her photos capture aspects of the event that haven’t changed that much. Her photos of the 1973 Pride Parade, for example, show marchers carrying banners and drums, as well as parents with children.

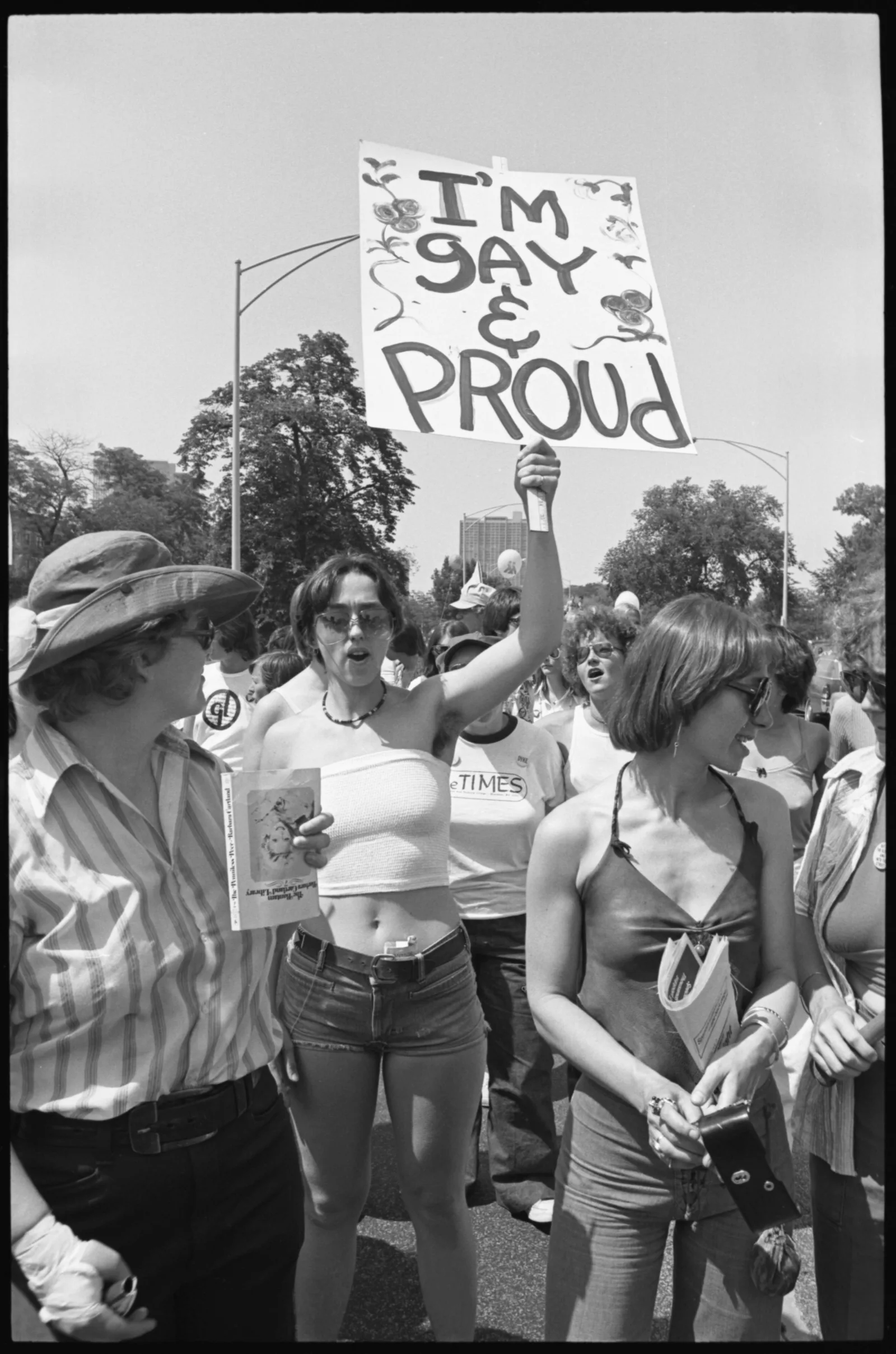

At the same time, many of her photos focus on the activism at the core of the early Pride marches–like a photo of a woman holding a sign reading “I’m gay & proud” from the 1977 Parade.

Militante’s photos also record some largely forgotten events of the decade. In a photo taken at the 1977 Parade, a large white van is covered in orange-shaped signs with slogans like “OJ causes brain damage!”—a reference to the orange juice boycott launched by gay rights activists against anti-gay rights singer Anita Bryant, who served as brand ambassador for Florida Orange Juice throughout the 70s.

.webp)

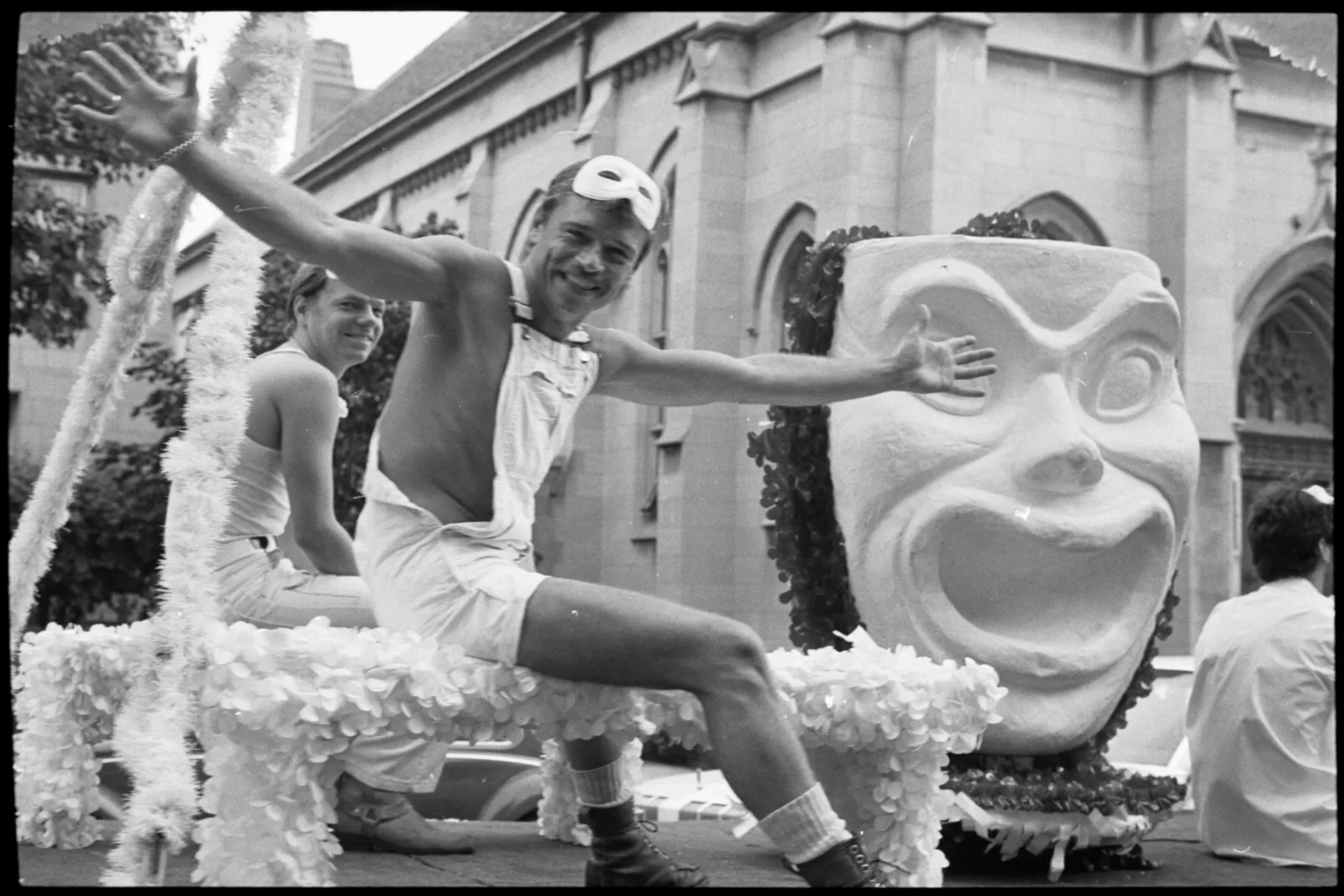

In addition to activists, Militante photographed the floats and costumed figures who would become fixtures at Pride Parades, as seen in images from the 1978 Parade.

She documented more intimate moments as well, including two figures seen in a photo from the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in October 1979.

About the Author

Matthew Clarke is the former Communications Coordinator at the Newberry.