This year, The Pattis Family Foundation Chicago Book Award, established in 2021 by the Pattis Family Foundation in partnership with the Newberry, has been awarded to Thomas Leslie for his publication Chicago Skyscrapers 1934-1986: How Technology, Politics, Finance, & Race Reshaped the City. In addition to awarding Leslie, the juried panel also recognizes John William Nelson as the shortlist award recipient for authoring Muddy Ground: Native Peoples, Chicago’s Portage, and the Transformation of the Continent. These texts are being awarded for telling stories that advance public understanding of Chicago, its history, and its people, while also resonating with the Newberry’s collections. With the Newberry being a repository of material related to Chicago and its history, there are many opportunities to find items in our collections that reflect the stories and themes presented in Chicago Skyscrapers and Muddy Ground.

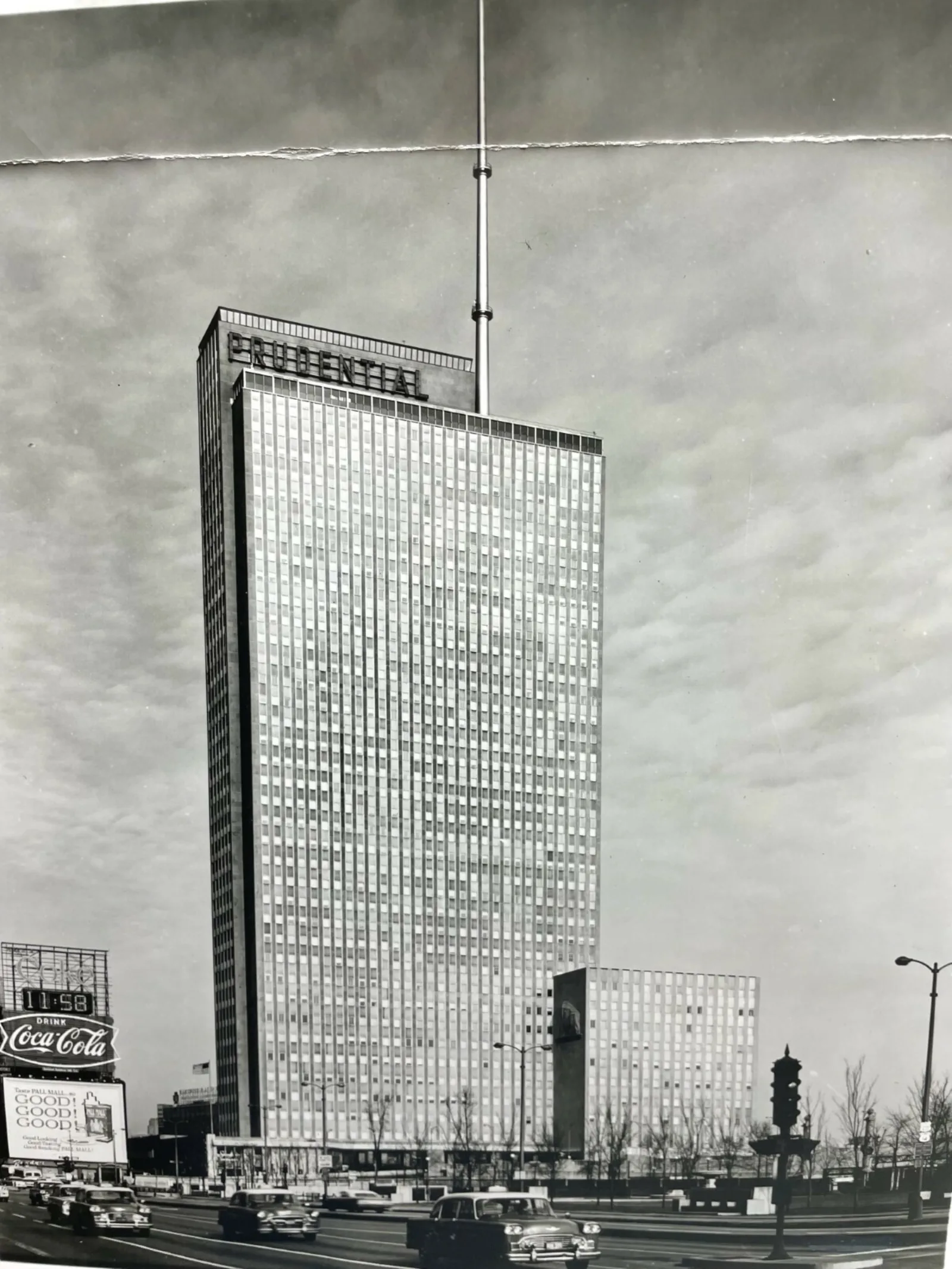

Both books focus on Chicago as a physical space, relying on visual aids such as maps and photographs that depict various aspects of the Chicago landscape. Chicago Skyscrapers includes numerous photographs of Chicago’s skyline to show the city’s built environment from the mid-twentieth century to the present. You can find material like this in our Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad Company Records, which feature plenty of midcentury photographs of the Chicago skyline in its advertising albums. The image included below was taken from this collection and is also featured as part of our current exhibition, Chicago Style: Mike Royko and Windy City Journalism, open until September 28.

In this same collection, the Prudential building (built in 1955) is highlighted, which is a key topic of interest in Chicago Skyscrapers. Leslie notes that the Prudential building marked a transition into the skyscraper era with it being the first skyscraper built in Chicago since the Great Depression. At the time, it was the largest building in Chicago and marked an investment in the loop as a burgeoning center of commercial development. As Leslie writes, “The Prudential thus stood as a transitional building; at the beginning of the loop’s massive revitalization and the application of technologies that would frame, clad, and condition the era’s tall buildings but also at the end of the city’s prewar moderne style (89).”

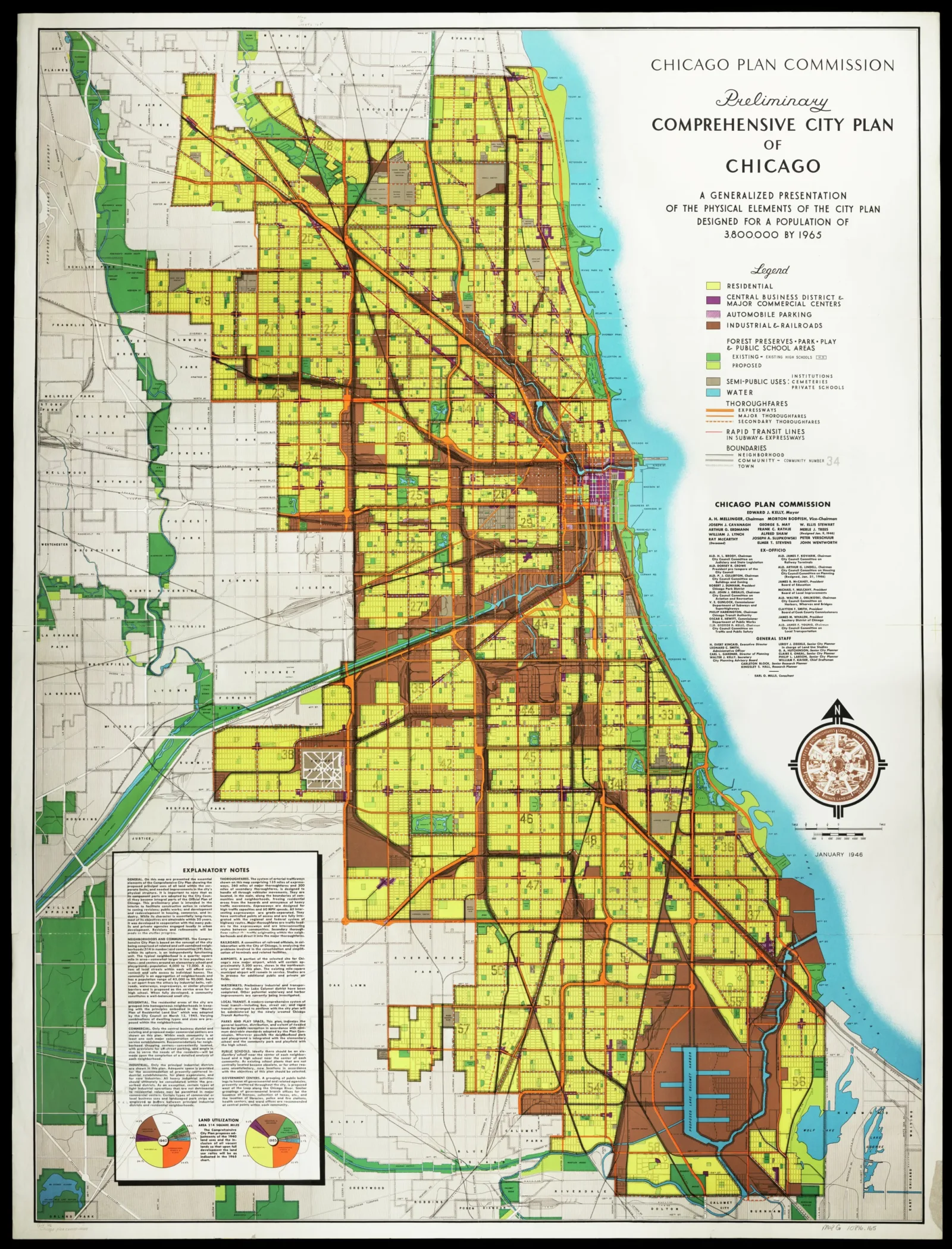

The Newberry’s collection also includes maps that show planned progressions of Chicago’s urban development in the 20th century, which is a major theme of Chicago Skyscrapers. The following map from the Chicago Plan Commission in 1946 is entitled the Preliminary Comprehensive City Plan of Chicago, which is self-described as “a generalized presentation of the physical elements of the city plan designed for a population of 3,800,000 by 1965.”

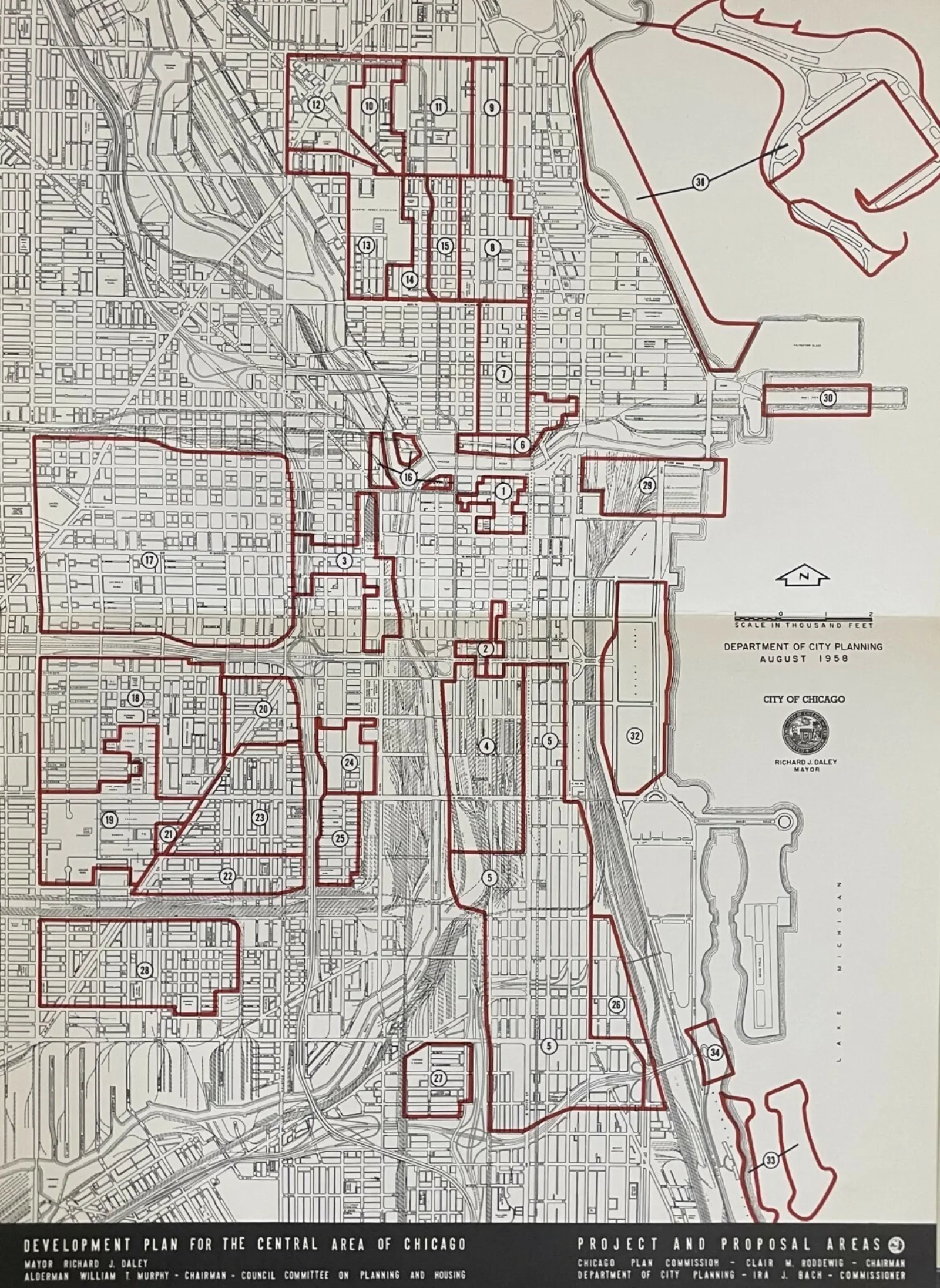

Leslie references the Chicago Plan Commission multiple times in Chicago Skyscrapers when discussing Mayor Richard Daley’s administration and the conception of the Department of City Planning’s Central Area Plan in 1958. The Central Area Plan exemplified the Daley administration’s ambitions towards “rebuilding the loop as a tax base, a political rampart, and a symbol of a new city..., building on the city’s reputation for commercial construction.” Leslie notes that this localized plan to alter the loop came at the expense of surrounding areas, as the plan saw, “outlying neighborhoods as either threats to or resources for downtown’s redevelopment. (136).”

Chicago Skyscrapers offers a comprehensive look behind the curtain of the modern era of skyscrapers, showing that while the grandiose nature of the cityscape depicts many innovative transformations of the 20th century, it also exemplifies the city’s greatest divisions. Leslie writes, “Building at large scale is never neutral; it concentrates resources and populations, alters the surrounding economic geography, and draws further attention toward itself and away from other areas (280).”

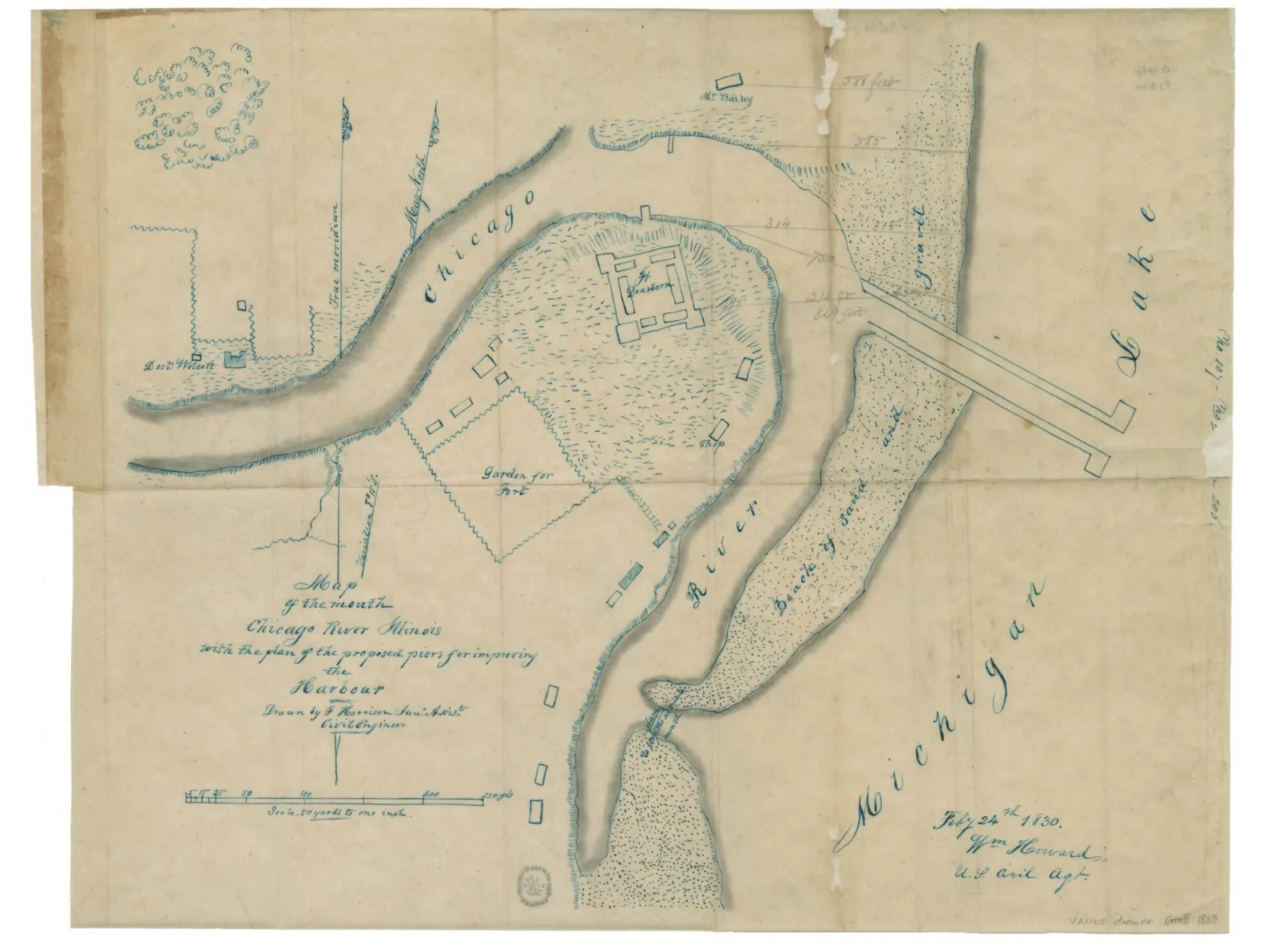

For Muddy Ground, author John William Nelson conducted much of his research here at the Newberry. He pulls from the library’s robust maps collection to provide depictions of portage in Chicago and the greater American interior, one of which is shown below.

With these maps, Nelson shows how a comprehensive understanding of the Midwest's portage translated to opportunities for gaining power. This lust for power reflected an ambition for imperial expansion and increased industrialization to transform Chicago into a landscape that could be controlled. Where, before, the interconnected waterways of the area allowed for cross cultural encounters and, in some cases, neutral passages, the overhaul of the land allowed the U.S to fulfill its conquest of Chicago. Near the end of the book, Nelson references George Robertson’s illustration, Chicago, Ill (1853), writing that the image represents “a triumph over natural geography and an enduring proof of American greatness in the interior (182).”

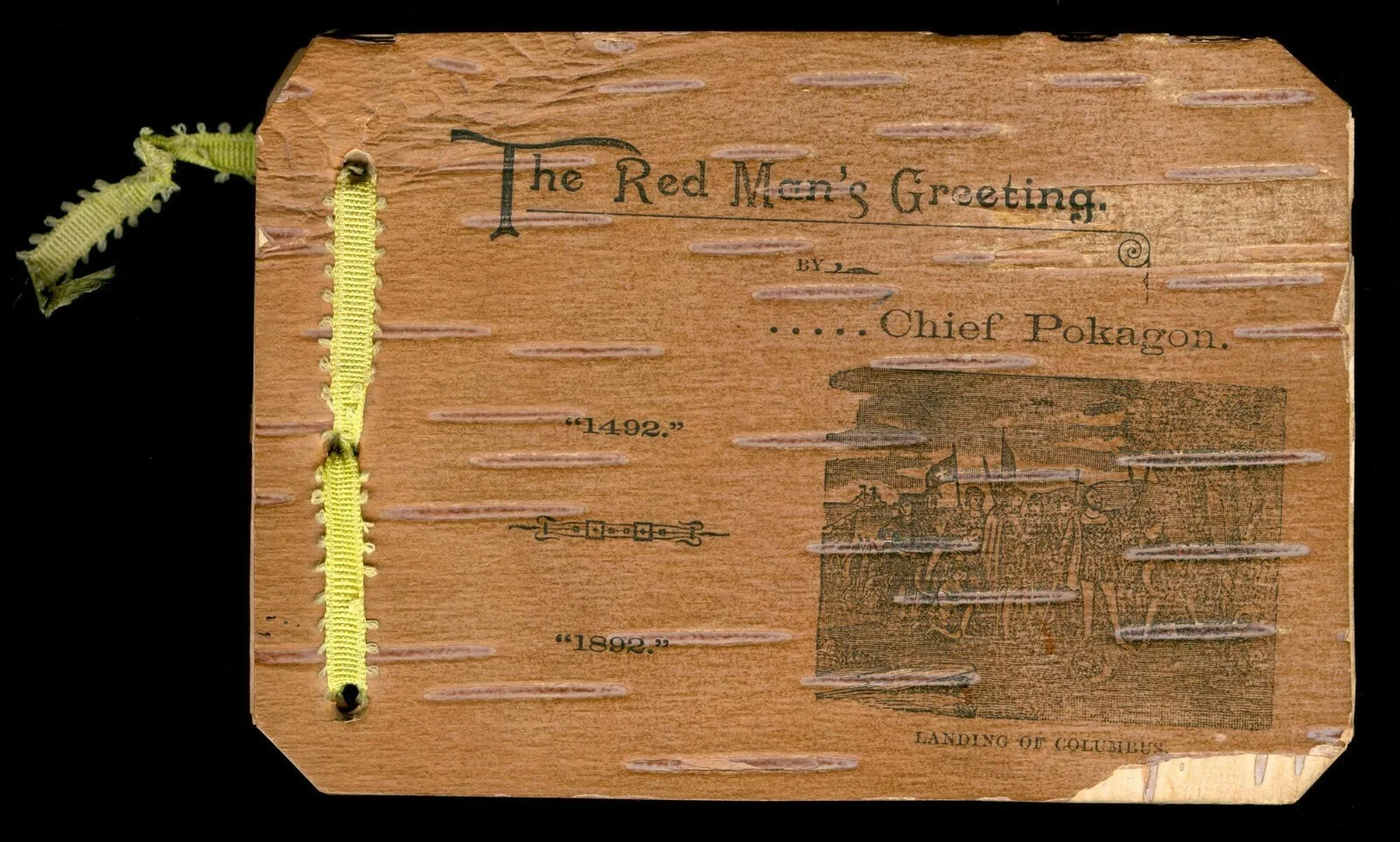

Many of these maps are the product of settler colonial ambitions, and often erase the presence of Indigenous communities. Despite this, Nelson is attentive to the Indigenous history that is inextricably tied to the events he mentions. In Muddy Ground’s epilogue, Nelson refers to Anishinaabe leader Simon Pokagon and his birchbark pamphlet The Red Man’s Greeting, which Pokagon authored in response to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. In The Red Man’s Greeting, Pokagon both laments the urbanization of Chicago’s landscape while also centralizing Native peoples in this history of alteration. As Nelson writes, Pokagon “would not let Americans celebrate their continent’s past without acknowledging the Indigenous experience inherent in that story (191).”

Both The Red Man’s Greeting and the William Howard map will be featured in our upcoming exhibition, Indigenous Chicago, opening September 12th.

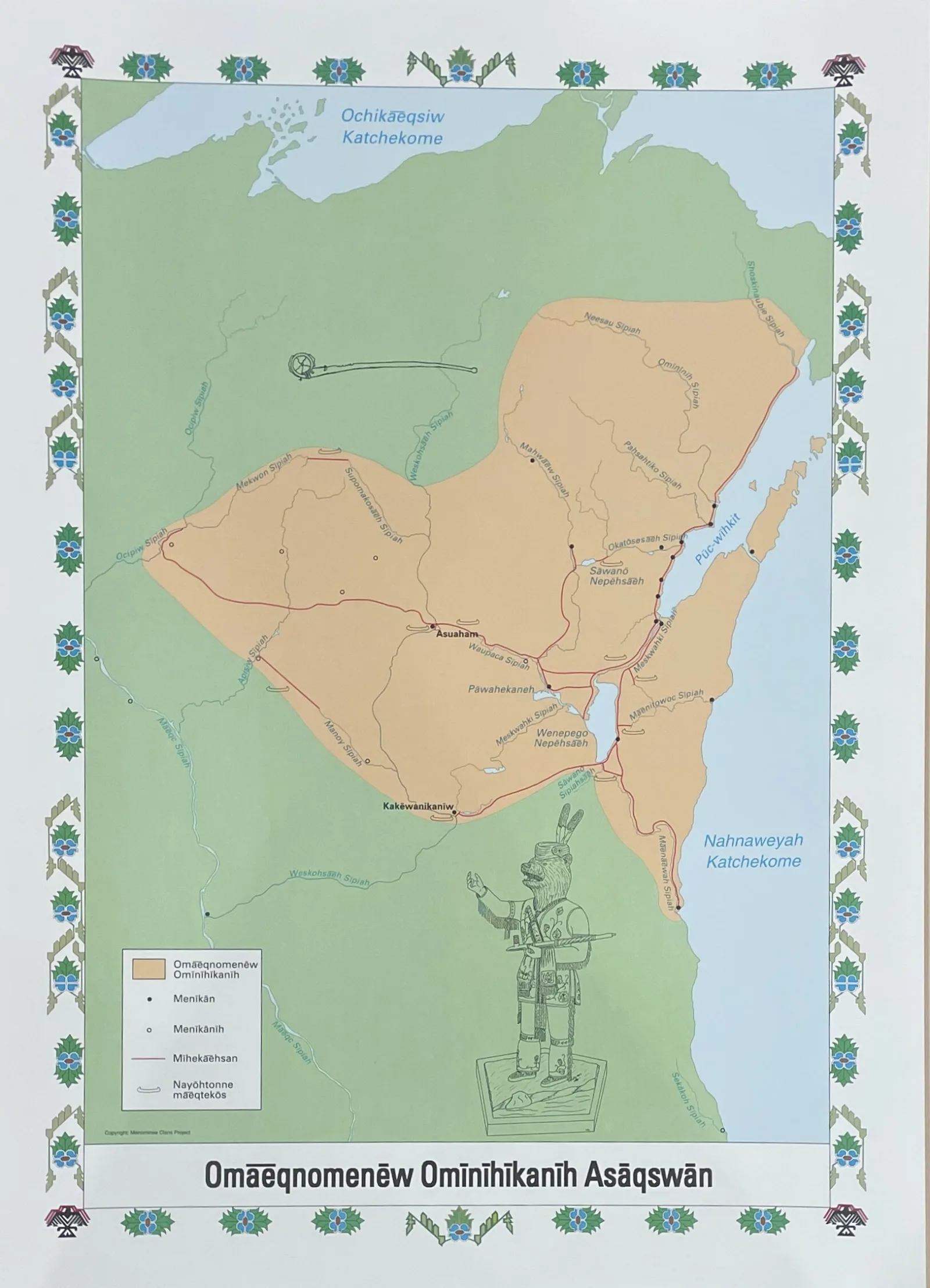

Beyond the items that Nelson researched for his book, there are other items at the Newberry that are indicative of Indigenous communities’ drive to centralize themselves to the lands they have settled upon since time immemorial. The Newberry holds Menominee language maps created by the Menominee Clans Story, which provide the Menominee names of lakes, portages, settlements, and other landmarks. Though these areas extend outside of Chicago to northern Illinois and Wisconsin, they are nonetheless tied to the stories and themes Nelson presents in his work, especially since the Menominee people utilized the portage routes spanning the Great Lakes regions.

All these items from the Newberry’s collection reflect the narratives presented this year’s Pattis Awardees. Through their respective books, Thomas Leslie and John William Nelson consider how issues of control and power altered Chicago’s physical and political landscape, thereby transforming vast populations and their ways of life. Both texts clearly mark the intrinsic ties between people and place, noting that changes to the land caused changes to the population that still reverberate today. The Newberry’s partnership with the Pattis Family in creating the book award was done out of the hope to showcase literature that transforms general perceptions about Chicago and its history, and the library’s collection provides an opportunity to delve into these themes even further.

Nico Marabella is the Administrative Coordinator for Public Engagement at the Newberry.