Sometimes penmanship aims to make writing more legible or pleasing to the eye. Other times, it strives to push the boundaries of what the hand can create.

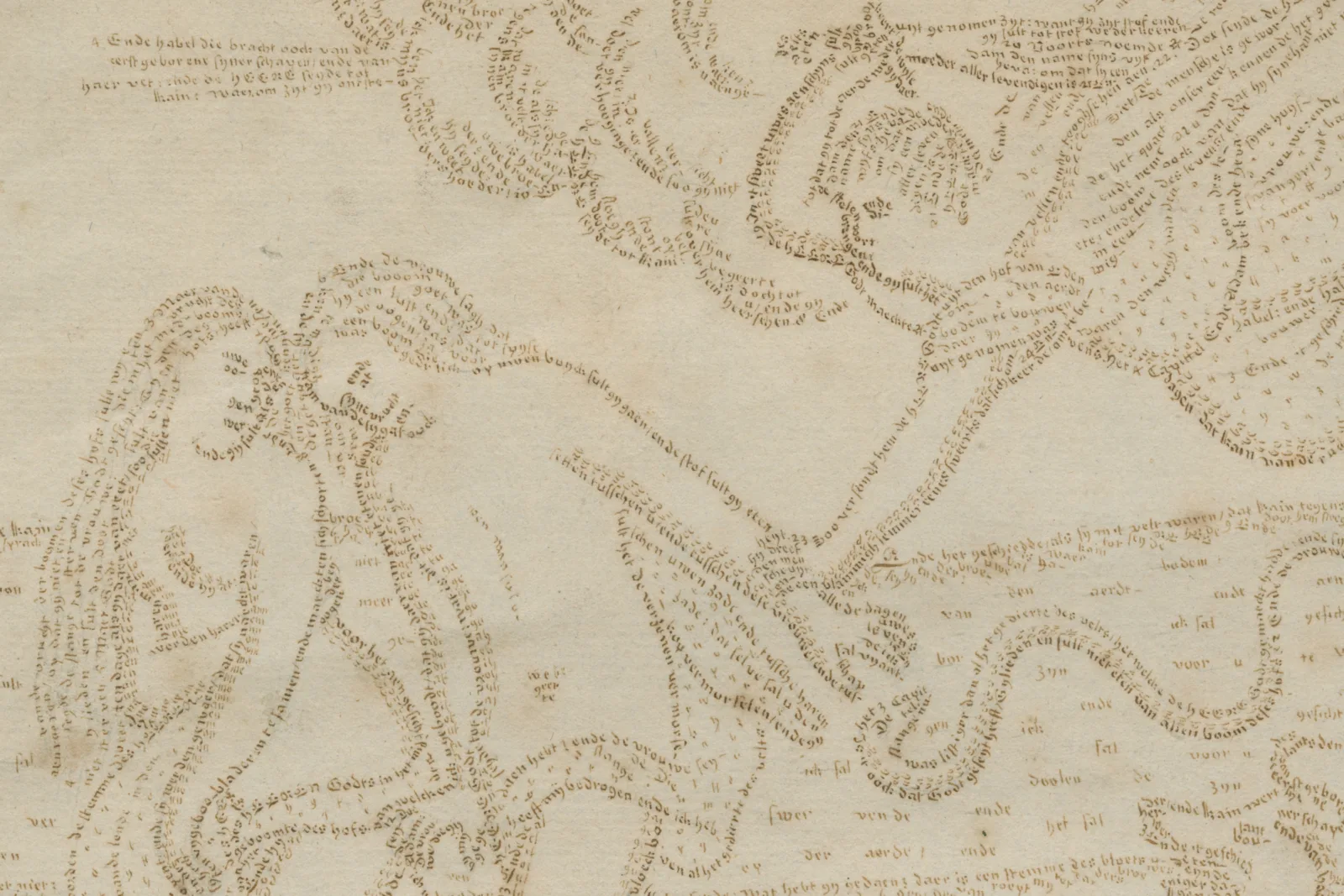

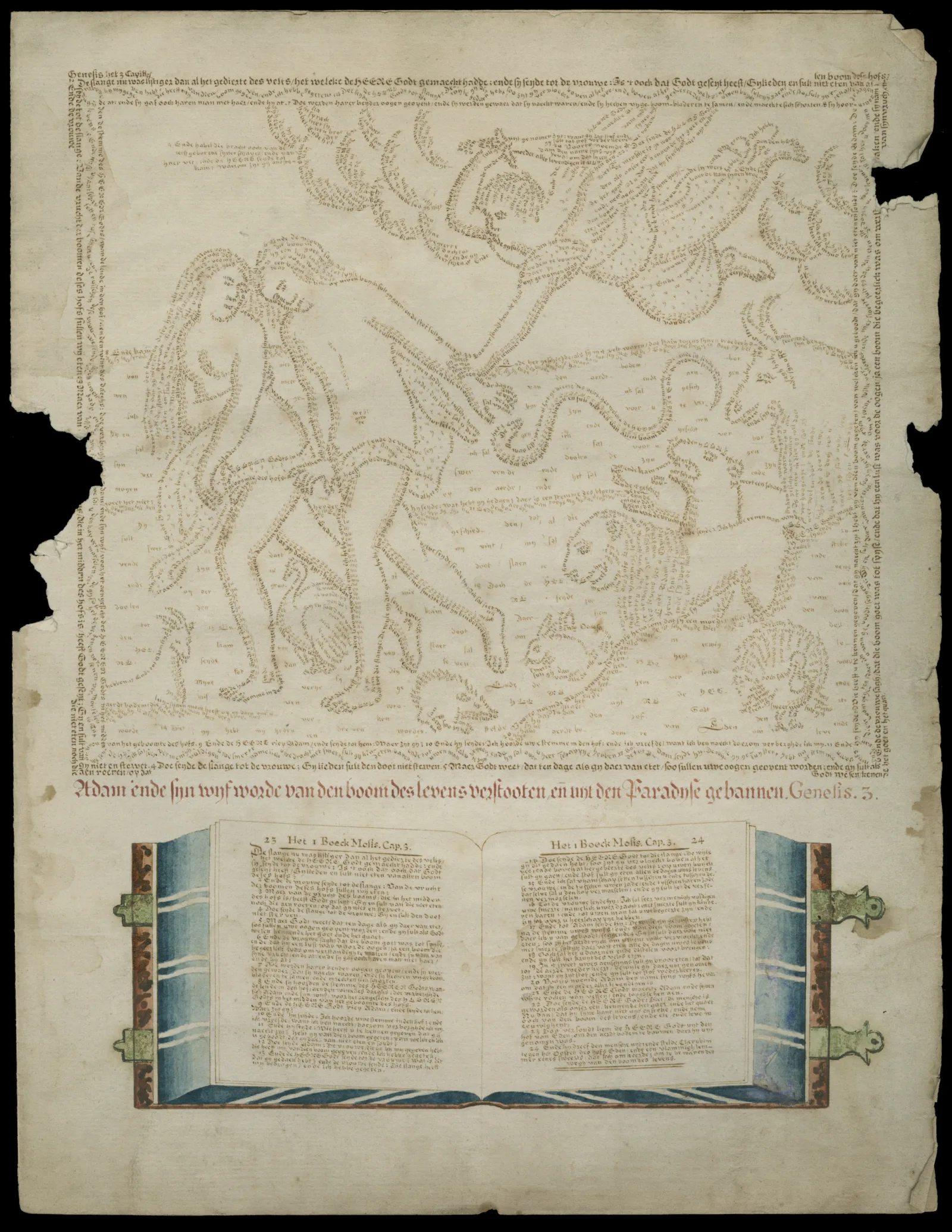

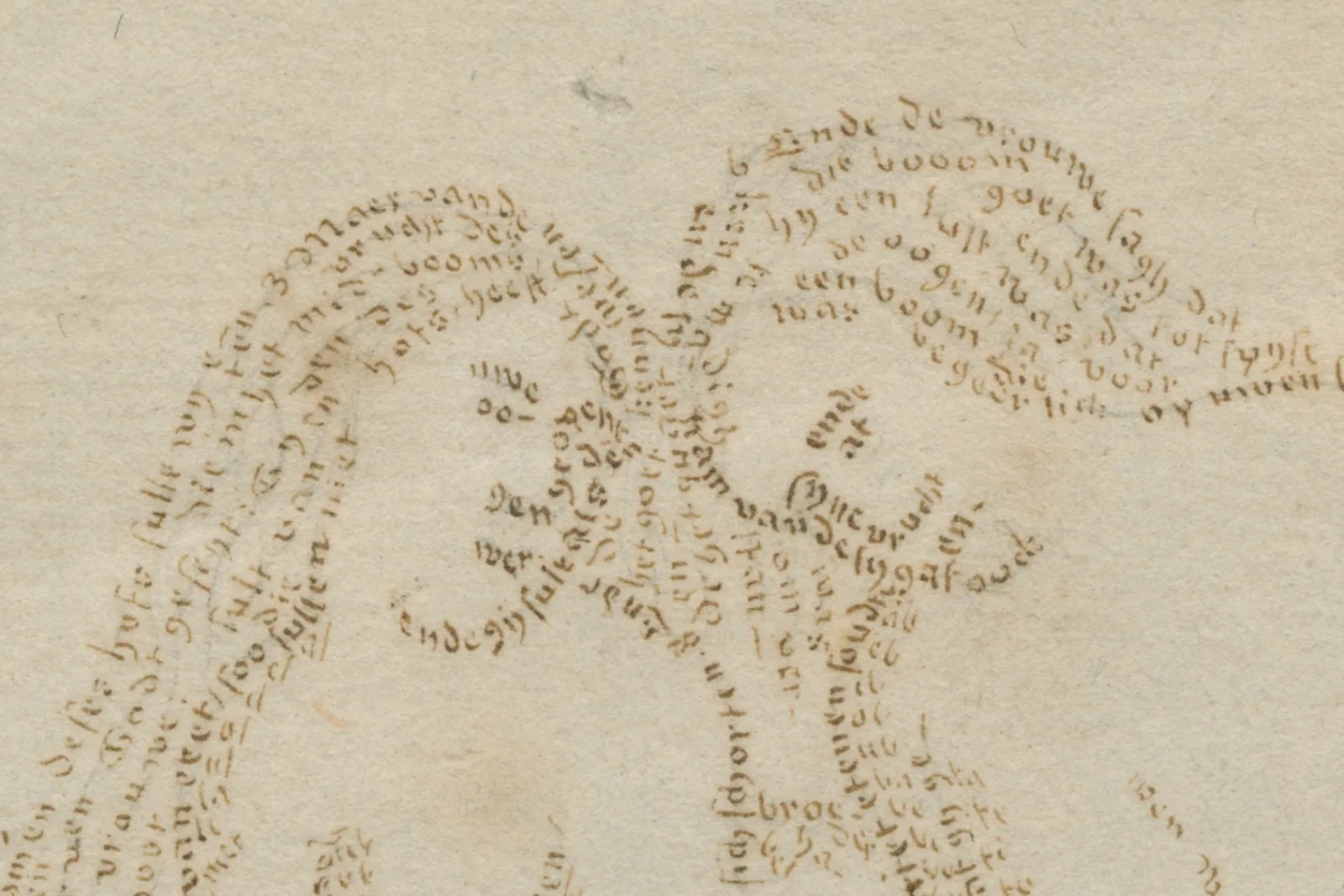

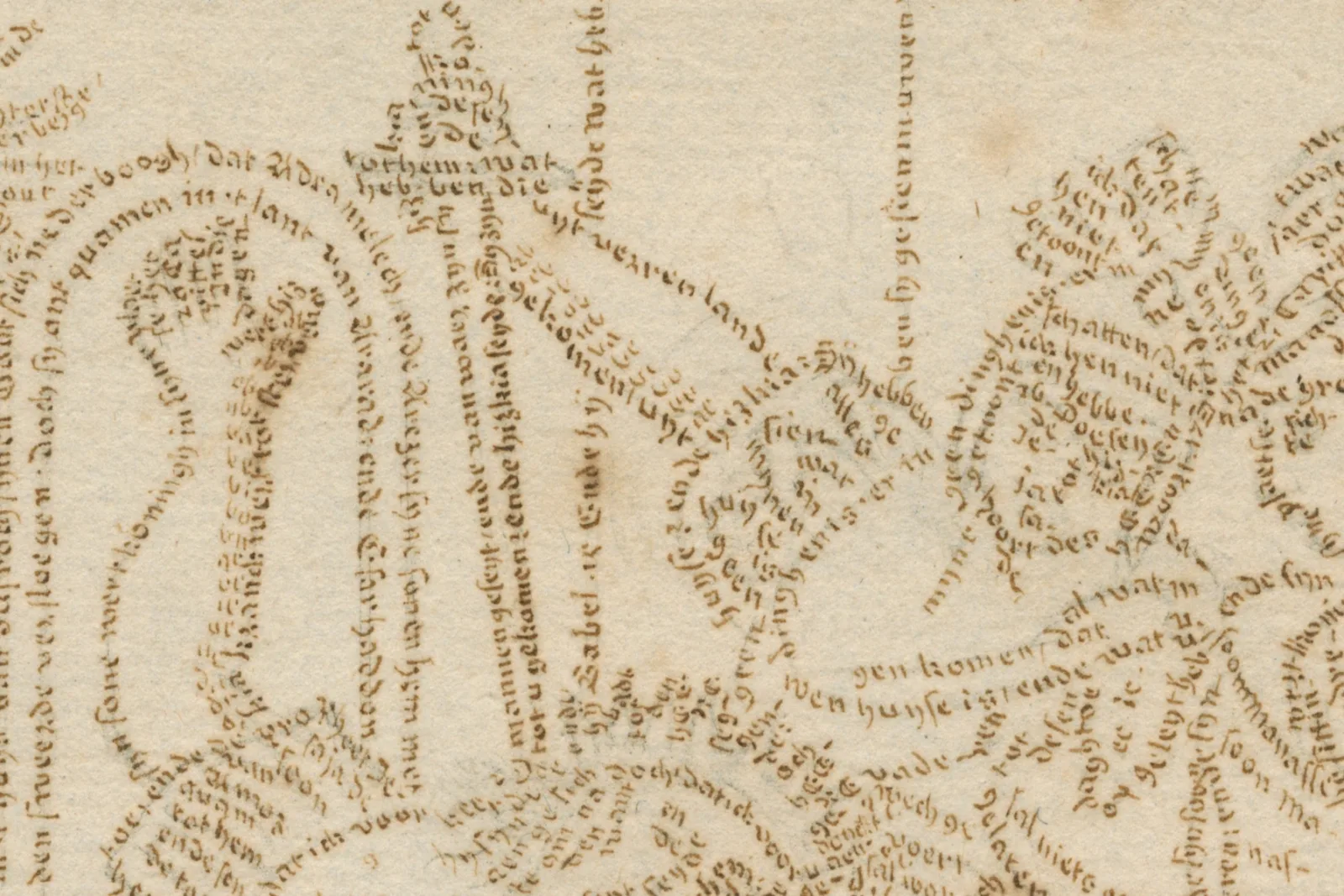

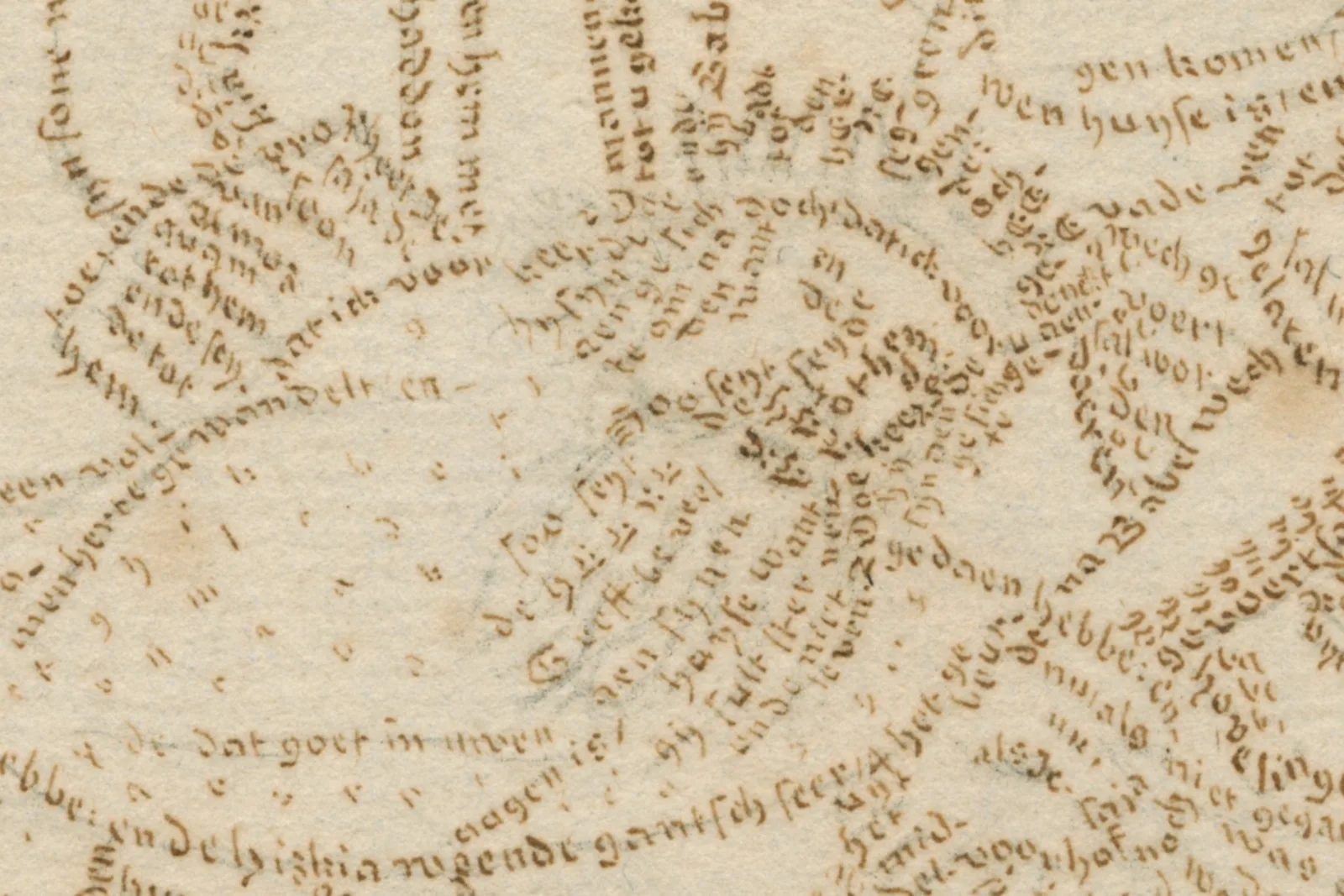

Skillful writing masters have dazzled readers with fancy flourishes, calligraphic animals, and self-portraits. While the Newberry’s current exhibition, A Show of Hands, is filled with beautiful illustrations and examples of virtuoso calligraphy, it is our specimens of micrography that I find the most astounding—and the most difficult to tear myself away from. Micrography, or microcalligraphy, is a type of calligram, an art form in which text creates an image. The image created is meant to visually represent the text.

Micrography dates to the 9th century and was originally used to decorate Hebrew Bibles. Even in the 16th century, as scribal (i.e. professional) manuscript production became less common, micrography remained a popular art form. The invention of lithography in the late 18th century meant that microcalligraphic writing could be easily reproduced in print, and printed sheets featuring biblical portraits or scenes were popular throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Newberry holds printed examples of microcalligraphy rendered in engraving or lithography. We also have a small collection of 19th-century Dutch manuscripts, with each sheet featuring a scene from the Old Testament rendered in the tiniest of handwriting; it was these manuscripts that I wanted to showcase in the exhibition.

All of the sheets are wonderful, and I had a hard time choosing among them. Adam and Eve or Samson and Delilah were early contenders (there’s something about calligraphic hair that I find enormously pleasing). I ended up selecting the sheet depicting Adrammelech and Sharezer killing their father Sennacherib while he worships in the temple of his god Nisroch (2 Kings, 19:37). Admittedly, my decision had much to do with the fact that this sheet was in the best condition, although I also relish the opportunity to point out the tiny calligraphic swords as a reminder that words can indeed hurt.

I chose to put the sheet on the wall instead of in a case because microcalligraphy is difficult to see. But the art is worth the effort and the inevitable squinting. There is a new detail to admire every time I look at this piece: the graceful, curved words that fill the border, the calligraphic knot at the bottom of the page, the expressiveness of the faces, and the tiny, single letters that make up Sennacherib’s beard. It is also great fun to alternate looking closely and then at a distance, and to admire how the text transforms into image and the image into text.

While I am always in awe of beautiful penmanship, microcalligraphy inspires so many questions: What kinds of pens were needed for this kind of work? Did the calligraphers use magnifying lenses? Did they all end up with horrible eyesight?

Even though the printed examples of microcalligraphy are wonderful, these handwritten works of art are truly transformative. They challenge us to rethink what can be created with just a pen and ink. They invite us into a world of creativity and skill and dare us to literally see handwriting in new ways.

About the Author

Jill Gage is the Custodian of the Wing Foundation on the History of Printing. She is also the curator of A Show of Hands: Handwriting in the Age of Print. The exhibition is on view at the Newberry from September 9 - December 30, 2022.