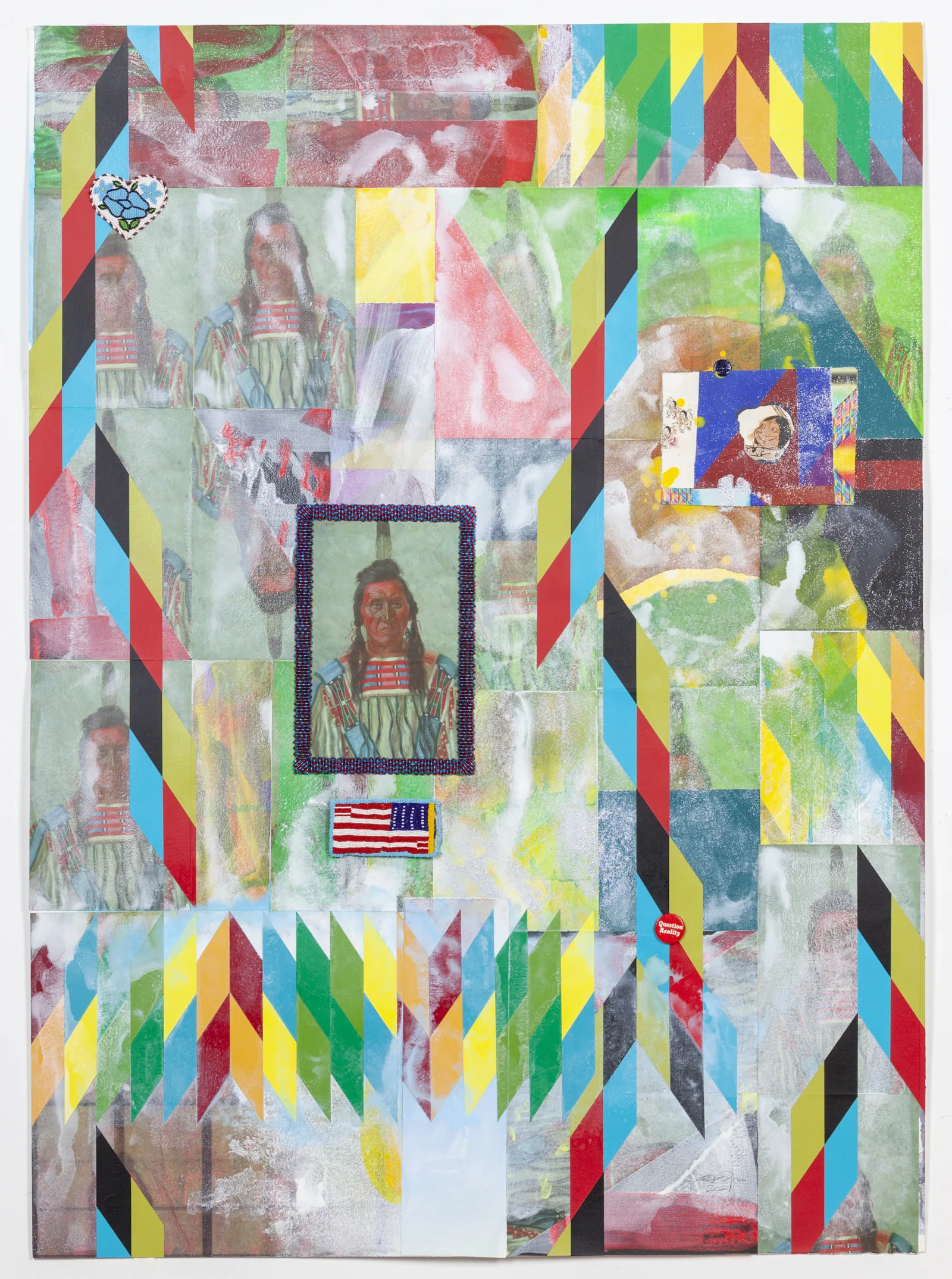

Sweet Bitter Love, presenting artist Jeffrey Gibson’s reflections on representations of Indigenous peoples in cultural institutions, is now on display at the Newberry through September 18.

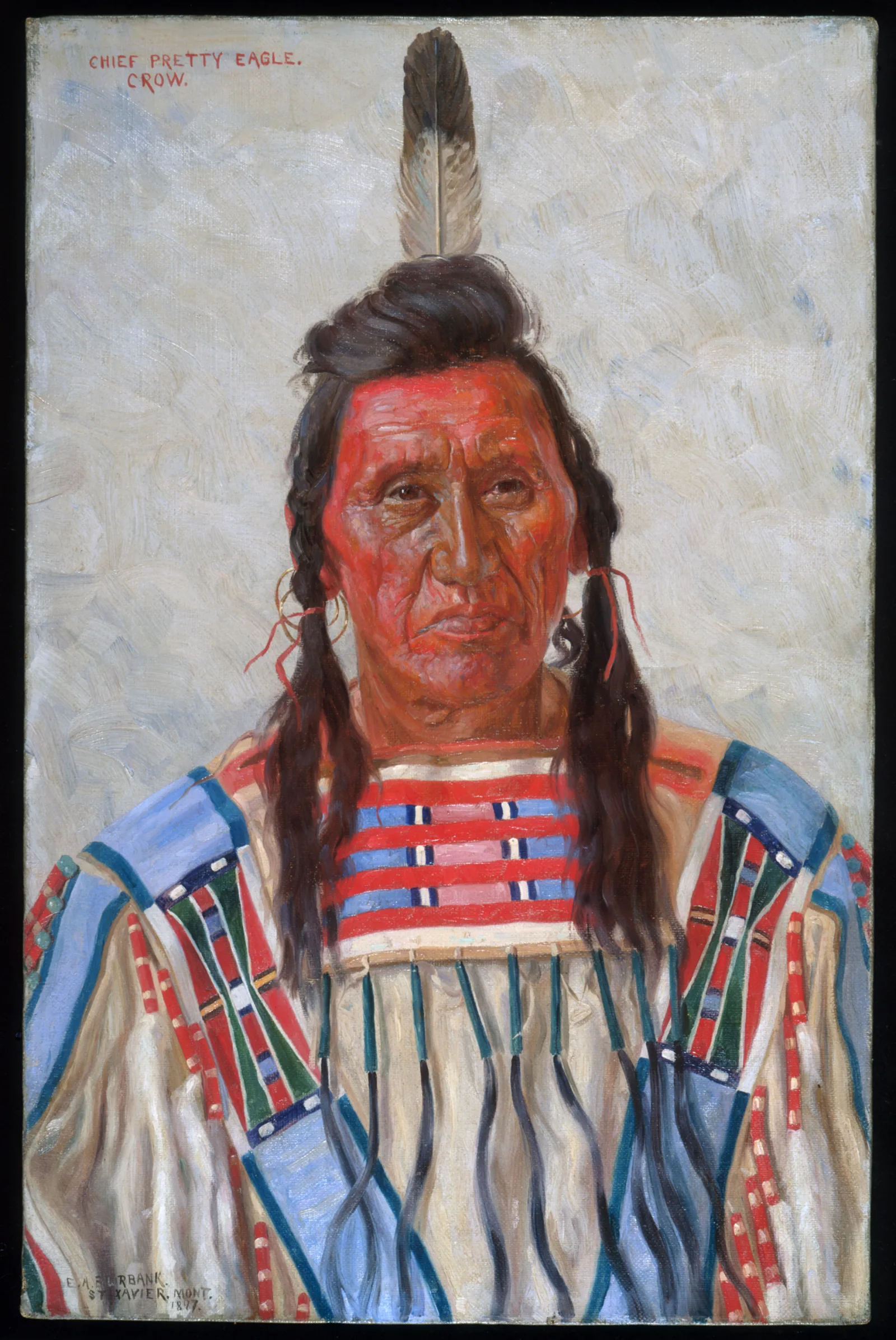

Responding to a series of late-19th and early-20th century portraits by Eldridge Ayer Burbank in the Newberry collection, Gibson (a member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and of Cherokee descent) refutes the stereotypical imagery that has reinforced pernicious myths about Indigenous people for centuries.

The exhibition is part of Toward Common Cause: Art, Social Change, and the MacArthur Fellows Program at 40, which is organized by the Smart Museum of Art in collaboration with exhibition, programmatic, and research partners across Chicago.

Analú López (Guachichil/Xi´úi), Ayer Indigenous Studies Librarian at the Newberry, recently spoke with Gibson about his evolution as an artist, the challenges of presenting the complexity of the past through art, and how his work might surface silenced voices in library and museum collections.

The following text has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Analú López: Tell our readers a little about yourself. How did you initially become interested in art? How have you evolved since then as an artist?

Jeffrey Gibson: I’ve been drawing since I was a little kid. Growing up, we moved around a lot because my dad served in the military and was stationed in Germany and Korea. I always identified as being kind of nomadic, and drawing became a portable activity that I could carry with me. My parents and teachers cheered me on as well. So pretty early on I knew that I wanted to be an artist; I just didn’t know what that meant. It was an aspirational idea.

After initially enrolling at the University of Maryland (where painting was my third major, behind Anthropology and Archaeology), I started going to a community college outside Washington, DC. I wanted to prove I wasn’t directionless, I was just not doing the right thing. I spent as much time in the Art Department as I could. I really indulged in photography, sculpture, and watercolor and oil painting. A professor whom I trusted recommended I then go to the School of the Art Institute [in Chicago]. It was there that I started understanding what it meant to establish a practice.

.webp)

AL: You work across so many different mediums and formats. How do you decide on the form a particular work of art will take when you’re creating?

JG: If you don’t come from an arts background, when you think of art you’re likely to picture painting or sculpture. My paintings from the early 2000s were totally abstract. My inspiration was bead work, basketry, and weaving. In my head, I was applying paint as if I were creating a woven fabric or adorning a textile. It confused people. When I talked about what the work was about, they’d say, “Oh, this looks like abstract expressionism. The story you’re telling is interesting, but I don’t see it in the painting.” It was out of that frustrating experience that I decided to stop referencing certain materials and actually use them in my work.

This also coincided with traveling around the country to visit with traditional Indigenous artists. I realized that someone choosing to make their own clothing—to live traditionally—was a kind of political choice of autonomy. I developed a different appreciation for Indigenous artists’ commitment to craft. I started learning from these people and incorporating what I’d learned into my work. I think of it as commissioning work from them: if someone was a quilt maker, I’d commission a quilt from them; if they were a silversmith, I’d commission a silver engraving.

In retrospect, I see this as the beginning of my focus on merging narratives and my own interests. I like to put different artistic traditions side by side—for example, teepee painting and German geometric abstraction. From there, I start trying to understand their similarities and strike a balance so those similarities can really surface.

AL: At first glance, people might see two contrasting visual styles and assume they have nothing to do with each other. But I love how your work brings out the similarities and shows people connections that they didn’t see initially. This brings me to my next question, which relates to the silences—the marginalized voices and the perspectives of the past—that exist in libraries and museums. Do you think art can surface these silences. And if so, how?

JG: I do think that’s a real possibility. History is overwhelming; it seems coherent, but when you really dive into it, it starts splintering so quickly. I realized at some point my job isn’t to try to control how the narrative rolls out of history. You have to almost let the chaos happen. Two events that happened concurrently may not seem to have any relationship if you look at them side by side. But we have to assume there’s some relativity between them. If I focus on one thread of history, I’m perpetuating a false narrative. Whether it’s my agenda or someone else’s agenda, it’s not the truth. The truth is really messy and it’s really uncontainable.

The challenge of working with archives, I think, is that you’re tempted to search for evidence that supports an argument. As an artist, that’s not my responsibility. My responsibility is to collect everything into a stew.

AL: Native American and Indigenous peoples have often been portrayed in stereotypical ways that reinforce the myth of the “vanishing race.” This is certainly true of E. A. Burbank’s portraits of Indigenous figures. How would you say your work is pushing back on this notion?

JG: The Burbank portraits don’t show the truth of what was happening to Native people in that time period [late 19th and early 20th centuries]. These paintings whitewashed the violence of settler colonialism, and they’ve influenced the way the public thinks about Native people. I’ve had to deal with that in my own lifetime.

Initially, I thought it was my responsibility to honor the people in the portraits. But then I started seeing the portraits as intersections of many narratives. And I am my own intersection. I thought how, with artists, whatever we make is truly a reflection of us. I eventually realized that what I’m making in response to Burbank is about me; it’s not about the individuals in those portraits. That entails accepting a self-centeredness that I think of as human nature.

I’m not so much pushing back on the Burbank portraits as trying to open them up. Hopefully, this may help people understand that everything can be a launching point for us to move from. The threads that are coming through are looking at all the elements that have led to who I am in relationship to this type of portraiture.

AL: What drew you to engage with the Burbank portraits in particular? Why not something else in the Newberry collection?

JG: Well, part of it was that I’m a painter and I’m familiar with this kind of painting—including not only the work of Burbank but of someone like George Catlin, too. These painters have always interested me because I’ve wondered; What would I do with their work? Would I riff off it in some way? As I’ve gotten more mature as an artist, I’ve given in to the fact that I really am process-based—meaning, I don’t know what the finished product is going to be. It’s a process of pushing the work to one point, putting it aside, picking it up again, and continuing until it arrives at a point where I can say, “Okay, this is everything coming together.”

When I started looking into the archives, it was such an overwhelming experience. Each document I picked up had its own story. One image that I kept returning to was trains. The reason trains were important to me was that the budling of the railroads is what defined a lot of relocation and removal acts affecting Indigenous communities. Being from Mississippi and Oklahoma, this history intersected with my own personal history. My great grandfathers spent their lives building something that would tear apart their communities.

Ultimately, I didn’t feel I could make a whole body of work about trains. The Burbank portraits offered the kind of collective subject matter I felt I could approach.

AL: As you might already know, railroads were central to the life and career of Edward E. Ayer [a Newberry benefactor and uncle of E. A. Burbank]. Ayer supplied lumber to the railroads. He used his wealth to build a personal collection related to American Indian history and culture, which would eventually become one of the foundational collections at the Newberry. That’s another interesting narrative that can be pulled from your engagement with Burbank.

JG: Even if the work itself doesn’t bring that out, hopefully conversations, like this one, around my work can send people into other directions.

About the Author

Analú López (Guachichil/Xi´úi) is the Ayer Indigenous Studies Librarian at the Newberry.