Among the many gems of the Newbery collection is a rare Missal (a liturgical book containing the text for the Mass) that was published in 1584 in Venice by the famous Giunta Press.

Drops of wax that have fallen onto the pages transport one from the Newberry’s quiet reading rooms to the animated spectacle of a sixteenth-century Catholic church. The Newberry Missal, placed on the altar under the flickering candle lights, would have provided the prayers and chants for the celebration of the Eucharist.

.webp)

This book had one more surprise for me. When flipping through the pages, I came across Pantalone and his servant Zanni: the two stock characters of the Italian comedy, better known as the commedia dell’arte (a term coined during the mid-18th century). How is it that such “irreverent” figures appear in a religious text as solemn as this Missal?

The Commedia dell’Arte

The commedia dell’arte emerged in the Veneto region of Italy around the mid-sixteenth century, at the crossroads between courtly and popular culture. Its early professional actors were organized in itinerant troupes, which held paid performances in both public and private contexts. Their improvised scenarios revolved around a series of stock plots borrowed from erudite comedy.

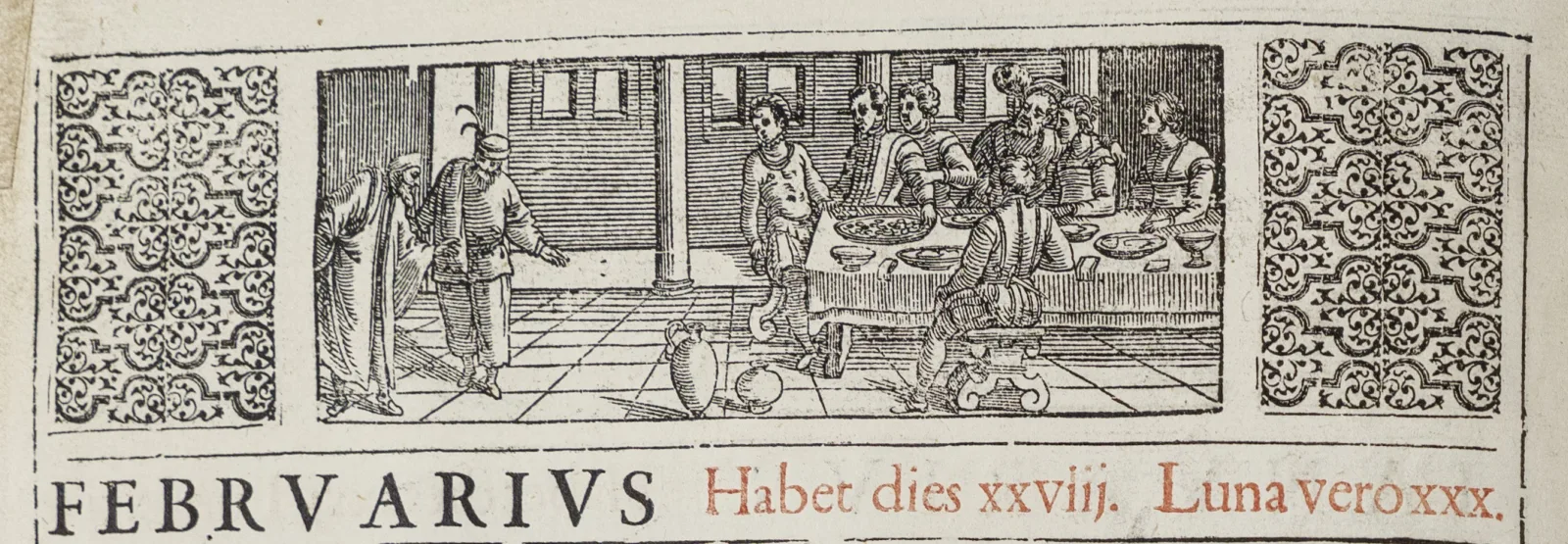

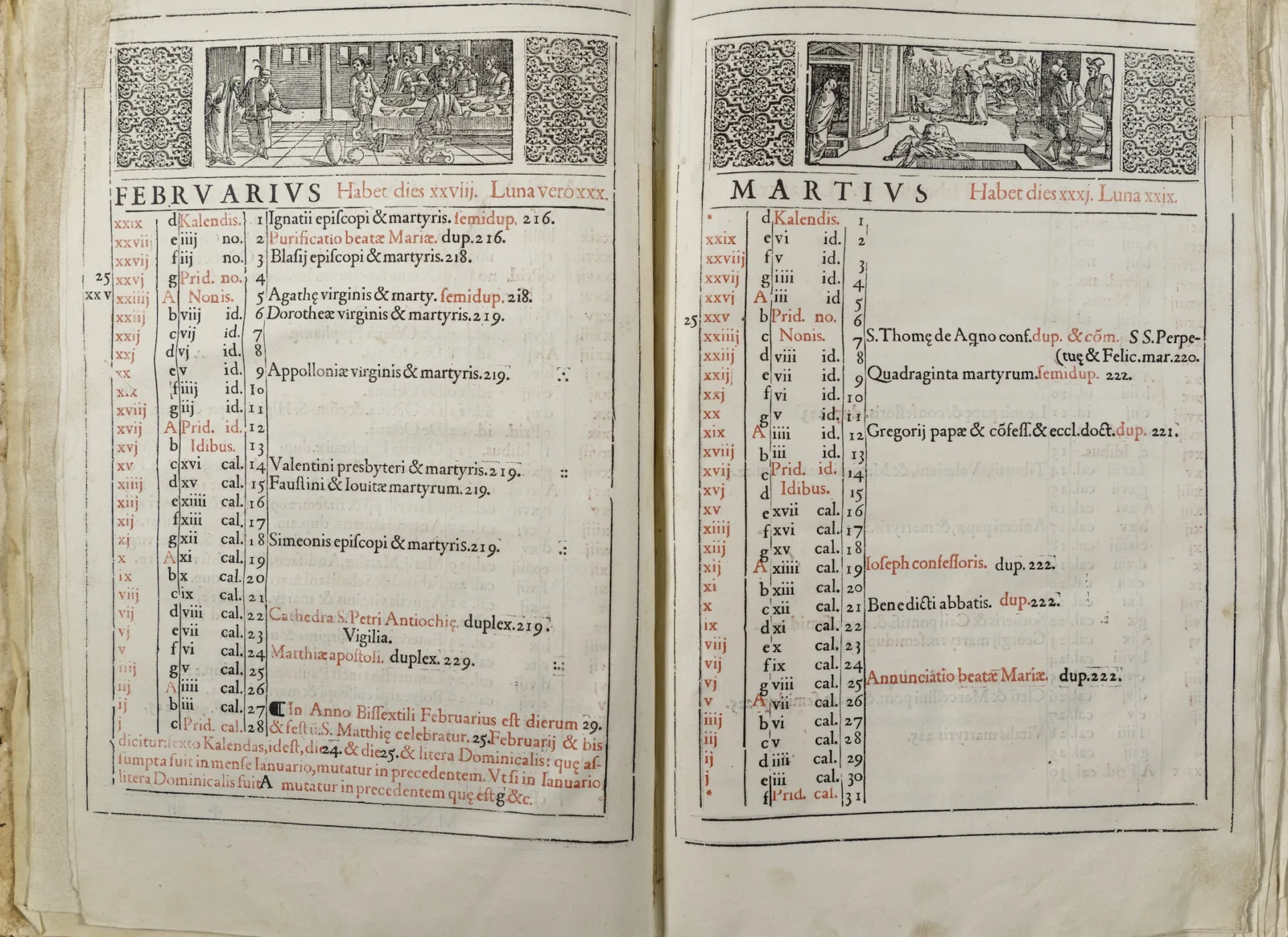

In the calendar section of the Newberry Missal, one finds a woodcut illustration of the two oldest characters of the commedia dell’arte during a banquet display. Pantalone, an avaricious old merchant from Venice, greets his audience in his characteristic pose: leaning forward with one hand behind and one in front. He wears a typical long cloak and woolen bonnet, and a mask covering half of his face, with a hooked nose and a white-pointed beard. Accompanying him is his servant Zanni, seen with his loose, ankle-length trousers and a long-sleeved jacket of light-colored linen held with a belt. He has a black beard and wears a brimmed hat with two long feathers.

Liturgical books like this one commonly opened with calendars that listed the saint days and feasts to be celebrated throughout the year. Following a long manuscript tradition, it was not uncommon to illustrate them with agricultural labors or occupations characteristic of each month. For example, in a Book of Hours (a book of prayers meant to be recited in private at regular intervals throughout the day) from around 1420, February is associated with the pruning of trees.

In the Newberry Missal, the woodcut of the comic group illustrates another February activity. By depicting a theatrical performance, the Newberry Missal referred to the civic calendar of Carnival celebrations taking place in February. The Carnival season was a period of liberation before the rigor of Lent, and it provided an ideal occasion for commedia dell’arte performances.

While market-square theater productions particularly raised moral concerns for both the Church and public authorities, the February illustration in the Newberry Missal presented a rather accepted form of theatre, one that related to the tradition of noble celebrations. It is interesting to notice that the Missal conceals an indispensable element of Pantalone’s usual costume, namely the phallic padded codpiece, a comic display of an old man’s virility. The latter was deemed perhaps too audacious for a book destined to sit on the altar of a church.

The Passage from Carnival to Lent

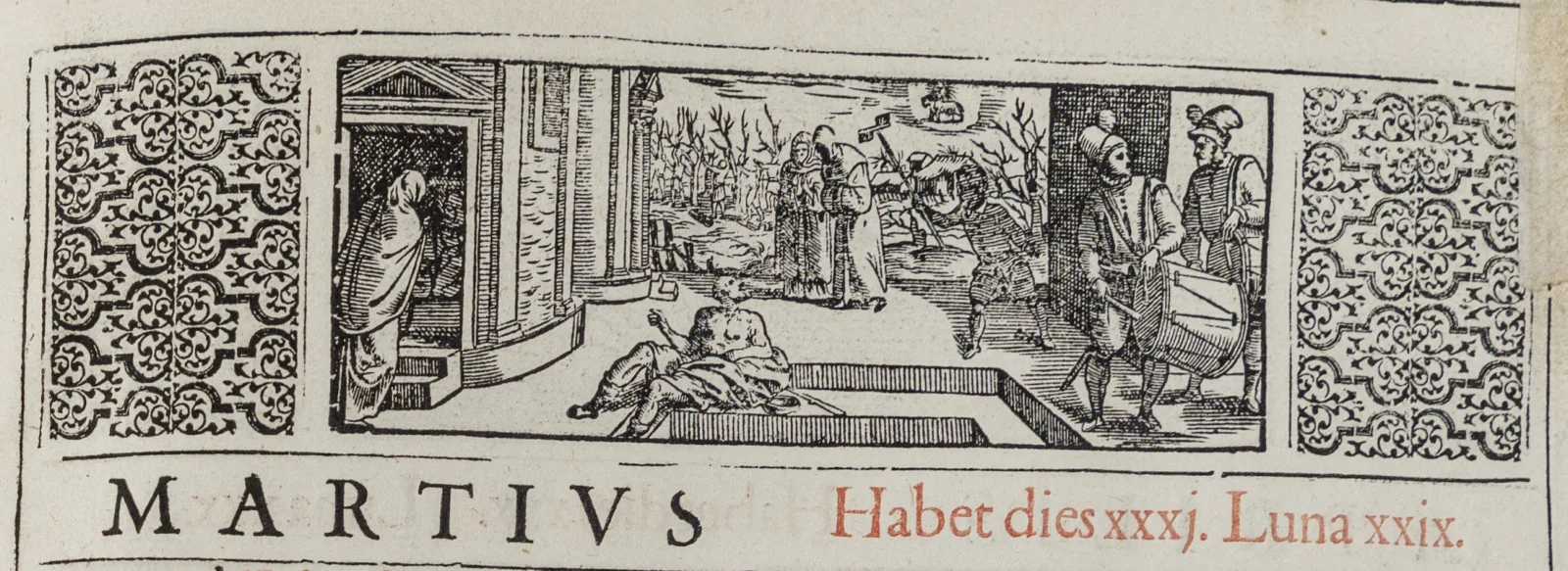

To understand why the rather unusual Carnival celebration was included in the February section of the Newberry Missal, we must look at the occupation represented in the following month of March, as well as to the overall context in which the Newberry Missal was created.

The March illustration in the Newberry Missal marks a radical change in the behavior of Early Modern Italians due to the start of the Lenten season on “Ash Wednesday,” forty days prior to Easter. The vignette shows pious men and women going to church. A beggar in the middle of the composition reminded Christians of the act of almsgiving (the charitable practice of giving food or money to those in need) expected during this time.

Thus, each year, the passage from Carnival to Lent proclaimed the triumph of spiritual and moral conduct. The calendrical imagery of the Newberry Missal mirrored efforts to reduce the excess of Carnival, emphasize the Eucharist, and encourage a strict observation of Lent. At the same time, it defended a division of the year according to both religious and civic rhythms, particularly in the face of contemporary Protestant attacks on feast and fast.

The stock characters of the Italian comedy, Pantalone and Zanni, were therefore brought to the service of the Church, to reflect on central religious ideas characterizing the end of the sixteenth century. In doing so, the Newberry Missal showcases an early and unique visual document for the history of Early Modern theatre.

To find out more about the commedia dell’arte within the broader development of calendrical imagery in sixteenth-century Italy, see Anca-Delia Moldovan, “From Carnival to Pious City: Scenes of Urban Life in the Bassano Series of the Months,” Renaissance and Reformation/Renaissance et Reforme, 44.2 (2021): 113−46.

About the Author

Anca-Delia Moldovan was a Monticello College Foundation and Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellow at the Newberry Library from 2021-2022.