By necessity, most of LGBTQ+ history has taken place in the shadows. There are centuries of people who never wrote anything down, who destroyed their own records, who recorded mentions carefully enough that casual readers could not discern them. June 28 will mark 55 years since the Stonewall riots, a series of protests in New York City widely recognized as the starting point of the modern gay rights movement in the United States, centuries after European colonists began enforcing Puritan family structures in North America. Despite devastating challenges that continue to this day, the decades since Stonewall have seen much wider acceptance and awareness of queer stories and history. We can track that shift in archives across the country, including the stacks of the Newberry.

Early twentieth century mentions of queerness in the Newberry collections describe sexuality in clinical terms. Douglas C. McMurtrie, whose archives primarily focus on his work as a designer and printing historian, also wrote papers on “sexual inversion.” This archaic term described people who suffered from the “disease” of homosexuality. In 1912, he published “Sexual Inversion in Women” in The Lancet Clinic. When describing a woman who dressed in “most masculine suits, straight tailor hats and heavy shoes,” he notes that “she is heaped with contempt and scorn by the normal and feminine women who see her. She seems, however, to rather glory in this attention and adverse criticism.”

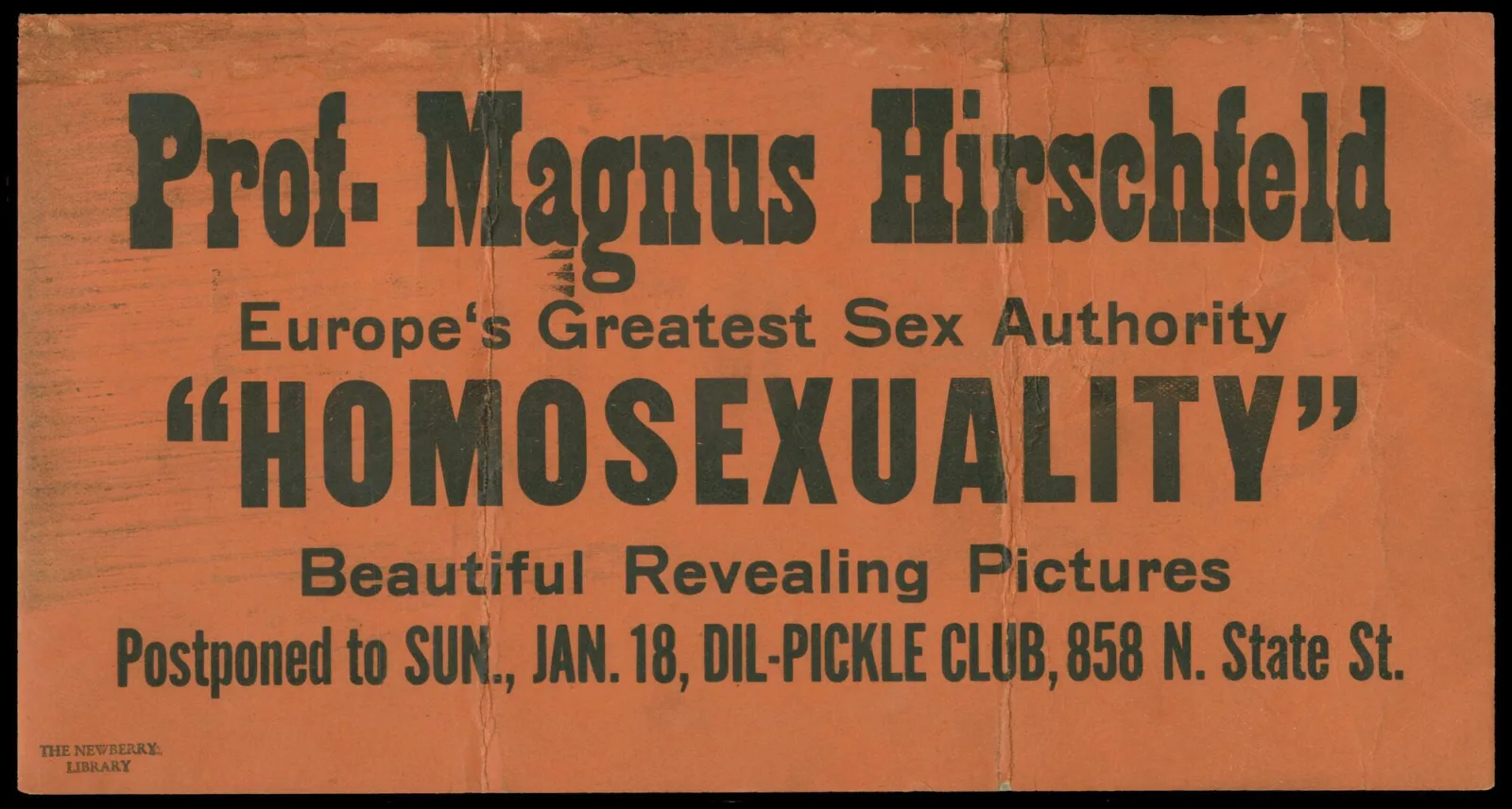

The Dill Pickle Club is also sprinkled with hidden gems of LGBTQ+ history. The bohemian club, located only steps away from the Newberry, was popular in the early twentieth century amongst radical activists, authors, and eccentrics. It was accepting of gay people at a time when this was exceedingly rare, even hosting iconic German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld. The physician and activist was repeatedly targeted by Nazis for being Jewish and an outspoken advocate for sexual minorities.

Collection items from later in the twentieth century show signs of mainstream progress. Valerie Taylor was an author and activist best known for her lesbian pulp novels in the 1950s-60s. Her books were unusual for giving her lesbian characters happy endings, rather than punishing them for their “transgressions” or returning them to straight relationships at the end. Newberry readers looking for personal insights into Taylor can find them in the letters she wrote to Jack Conroy.

A Midwest author prominent in Chicago leftist circles, Conroy struck up a friendship with Taylor. Taylor, writing under the name Velma Tate, corresponded with him for many years. Her letters frequently center around publishing, labor organizing, and Vietnam War protests, all of which are discussed with her trademark wit. While she frequently alludes to the pulp novels she writes, she is not explicit about her sexuality in the letters. She refers to her romantic partner, the lawyer Pearl Hart, as a “dear friend.”

Hart is, in fact, an icon of Chicago queer history. She’s one of the namesakes of Gerber/Hart Library and Archives, which is an invaluable resource in Chicago as a dedicated LGBTQ+ library and archive. The Newberry has an informal relationship with Gerber/Hart and occasionally speaks to them about LGBTQ+ acquisitions. These days, queer history isn’t just glimpsed in larger collections or found in dedicated repositories–it’s a priority across a wide range of archives.

“LGBTQ+ history is very hot in the book collecting world,” according to Matthew Rutherford, Curator of Genealogy and Local History. He, like many curators at the Newberry and other libraries across the country, are trying to bring this history out of the shadows and into archives where they can be preserved and made accessible for future generations. The DEI subcommittee of the Collection Development Steering Committee recently identified LGBTQ+ family histories and communities as one of their key collecting foci.

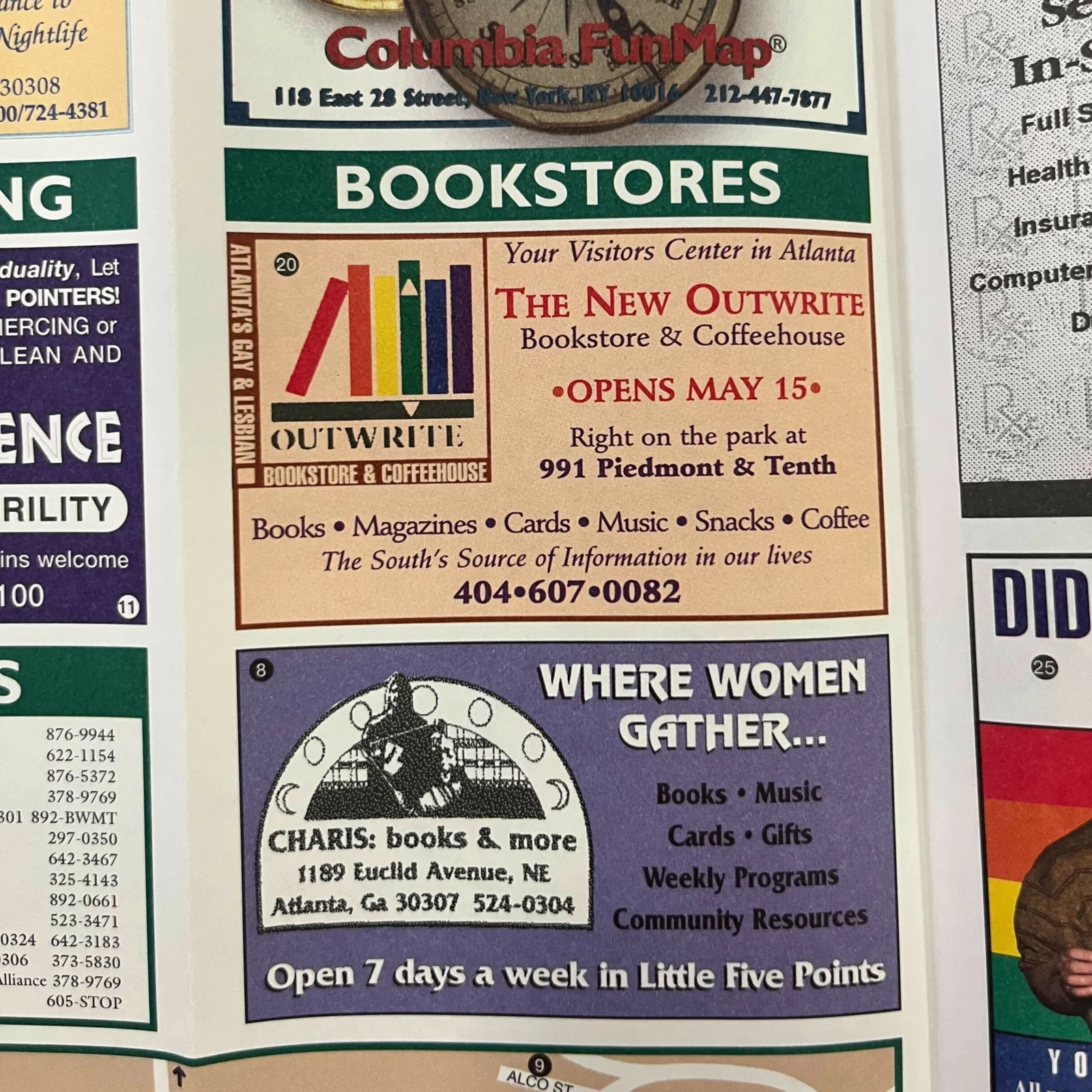

Some recent examples are the FunMaps and Damron travel guides, acquired by David Weimer, Robert A. Holland Curator of Maps. These resources provide maps and short descriptions of queer-friendly locations in different cities. While both companies are still publishing today, the recent Newberry acquisitions are primarily from the 1990s. The actual locations on the maps are interesting enough markers of cities over time, but the ads make them especially compelling. The images from gay clubs and bookstores–most of which have since closed–create a time capsule of LGBTQ+ community.

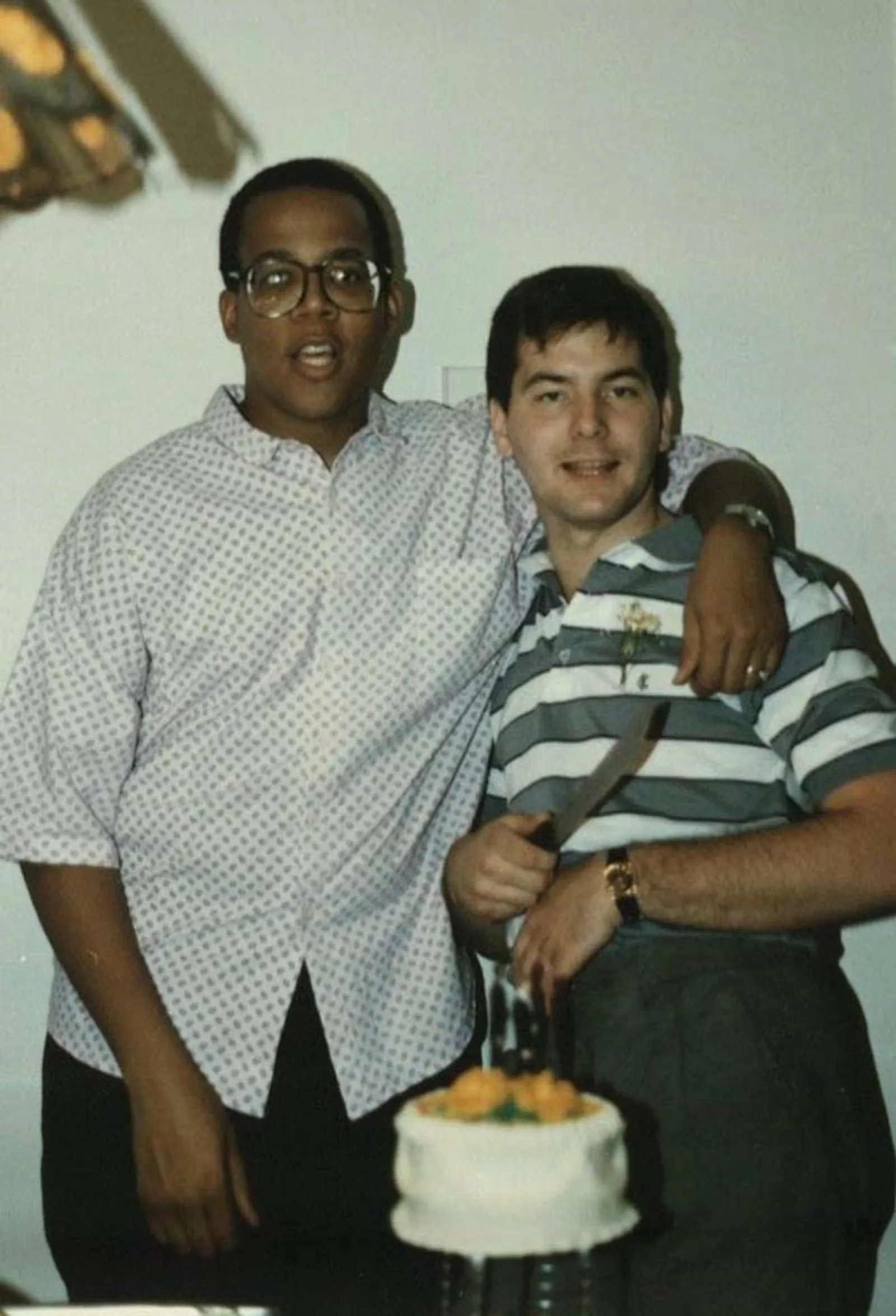

One of the most exciting recent acquisitions is the Kenneth Martin and John Dooley scrapbook. This scrapbook and photo album documents the lives of Kenneth Martin, a gay African American high school teacher, theater director, and AIDS activist, and his husband John Dooley, a gay white man. You can read more about the Newberry's acquisition of the Martin and Dooley scrapbook here.

The scrapbook is a rich text of gay domestic life in 1980s Chicago. Amidst fighting alongside their community for every scrap of healthcare and political progress, Martin and Dooley built a life together. We are lucky they chose to chronicle that life so that forty years later, we can learn about them: not because they were extraordinary, but because it is desperately important to understand ordinary people throughout history.

We don’t know the name of the woman in McCurtrie’s paper who wore “masculine suits” and felt pride in the “contempt and scorn” showered upon her. We don’t know the names of all the LGBTQ+ people who passed through the Dill Pickle Club, searching for a sense of belonging and understanding. But we still find them in the archives, in the articles and ephemera that point to their lives over a century ago. We find Valerie Taylor alluding to her relationship to Pearl Hart in the 1960s; we find Kenneth Martin and John Dooley living proudly in the 1980s. Who knows what we may find next?

If you know of a piece of LGBTQ+ history that could find a home at the Newberry, please reach out to a curator.

About the Author

Quinn Sluzenski is the Digital Initiatives Assistant at the Newberry and a volunteer at Gerber/Hart Library and Archives.