“On the 1920 Campaign Trail” is a series of blog posts documenting the 1920 election season. Paul Durica, the Newberry’s former Director of Exhibitions and curator of Decision 1920: A Return to “Normalcy,” will spend the next few months reporting and commenting on the campaigns of Warren G. Harding (Republican), James M. Cox (Democrat), and Eugene V. Debs (Socialist).

Paul will track the ups and downs building up to the election, as the candidates appeal to voters during a time that parallels our own: barely removed from a global pandemic and riven by unrest around racial and economic inequities.

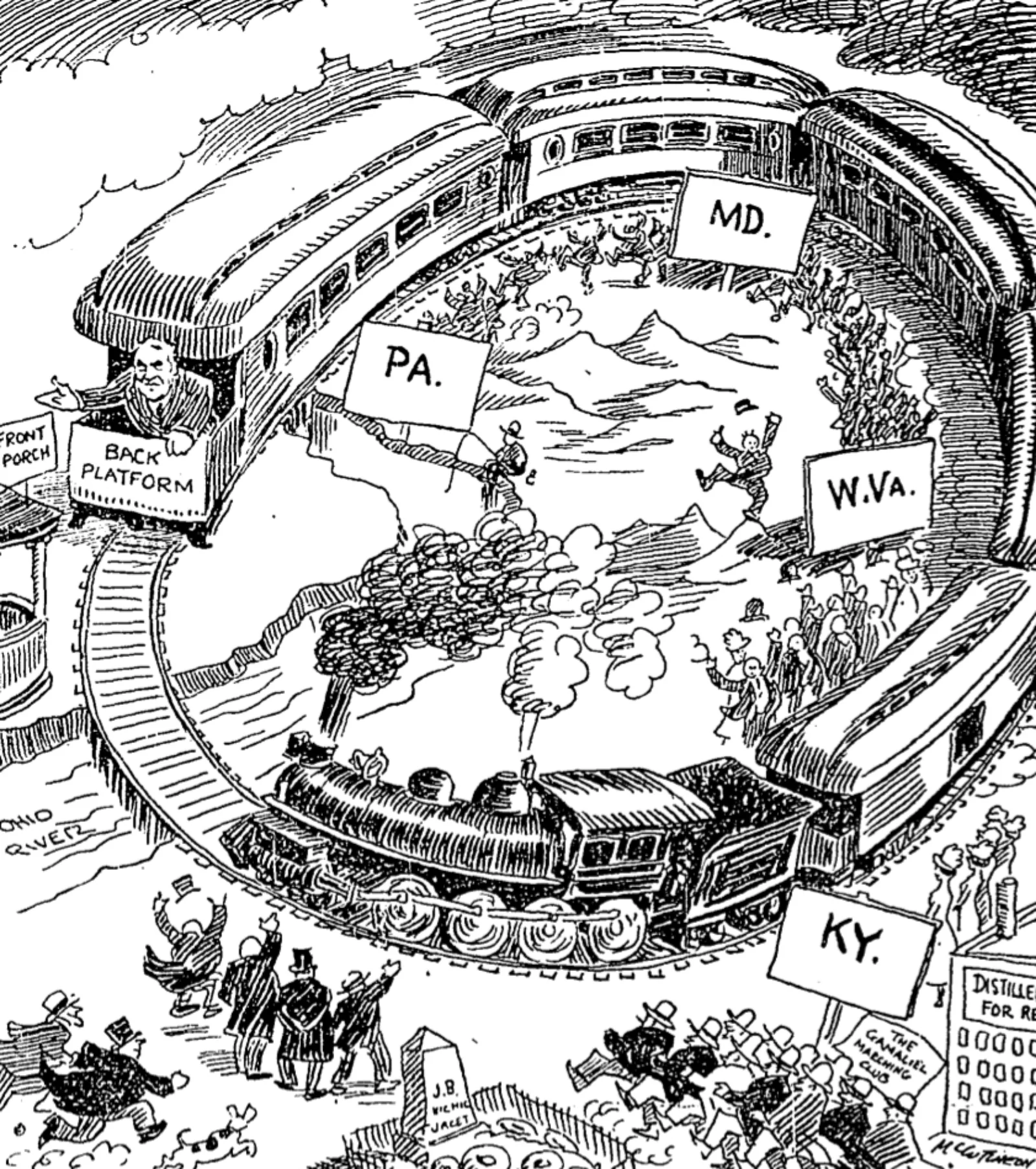

With election day quickly approaching, the candidates for both major parties took to the rails. For the Republican candidate, Senator Warren G. Harding, the trip marked a detour from a campaign that had been waged on the front porch of his house in Marion, Ohio.

On the eve of his departure, Harding welcomed close to three thousand traveling salesmen to his home to hear a speech book-ended by performances by a jazz band and glee club, both from Columbus, as well as several local acts. Speaking two days later at the Fifth Regiment Armory in Baltimore, Maryland, Harding advanced his case against the “one man rule” practiced by President Woodrow Wilson during the Great War and the treaty negotiations that followed. Before a cheering crowd of 18,000, Harding ascribed the “one great failure…of America’s leadership was due to the most part to the fact that one man attempted to speak not only for the United States but for the rest of the world.”

While Harding headed out, Ohio Governor James M. Cox headed back from his speaking tour through the western states to his campaign headquarters in Dayton. He predicted that he would carry at least eight of the states he’d recently visited in the election but refused to name them. Despite expressed optimism, Cox had been dogged near the end of the journey by questions about his position on national prohibition and reports that he had used his office to help the sons from two prominent families avoid service in the Great War.

The Cox campaign in a literal sense went off the rails just outside Peoria, Arizona, when the train upon which he was traveling jumped the tracks. While the Governor, seated in his private car, the Federal, was unhurt, the same could not be said of some of the other passengers and the crew. Ignoring pleas to stay away from the overturned locomotive at the front, Cox assisted the injured and ensured they were whisked away by automobile to hospitals in nearby Phoenix. An apologetic engineer assured the Governor that there was nothing political about the accident. “Oh, I know where you railroad men stand,” said Cox as he shook the man’s hand.

About the Author

Paul Durica is the former Director of Exhibitions at the Newberry.