When Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi was sold at auction in 2017 for $450.3 million, it set a new record for the highest known price paid for a painting. The sale set the art world abuzz not only for its extremely high price but also because several aspects of the painting’s authenticity had been – and continue to be – questioned by experts.

- Was the painting actually by Leonardo or a copy by a student?

- Who had owned the work and where had it been since the sixteenth century?

- How much of the original paint and board was left after conservation?

As an art historian, I am deeply interested in these questions, particularly how we assess the value of art. While one person might appreciate the religious value of Salvator Mundi’s depiction of Christ, another might value its historical insight into painting techniques. And increasingly, many collectors buy art as a financial investment, with the hope that it will increase in value over time. This growth in speculative collecting has fueled a massive expansion of the international art market over the last few decades. According to the most recent annual report published by Art Basel & UBS, global art sales totaled an astounding $65 billion in 2023 alone.

Yet the value of a work of art can be quickly undermined if revealed to be faked, forged, or manipulated in an undisclosed way. In 2022, the FBI raided the Orlando Museum of Art and seized twenty-five paintings that were exhibited as works by Jean-Michel Basquiat but later revealed as forgeries made after the artist’s death. Those involved were later charged with conspiracy and wire fraud – in other words, attempting to profit from fake art.

This tension between art, money, and authenticity is the focus of my research as a long-term fellow at the Newberry. My book project, Antiquarian Speculation: Art, Credit, and Collecting between Early Modern Europe and the Ottoman Empire, examines how early modern artists and collectors conceptualized (and often manipulated) the value of art and antiquities from the Eastern Mediterranean. Many sought financial profits, but some also pursued social or intellectual credibility among their peers. What complicates this topic further is that copying the work of another artist was not necessarily an illegal or deceitful practice in the early modern period. Young artists developed skills through imitation, and many professionals copied older artworks as a pedagogical exercise and a form of competition between “the ancients” and “the moderns.” Moreover, the Renaissance precursors to modern copyright regulations, known as privileges, were still being developed and negotiated in the sixteenth century.

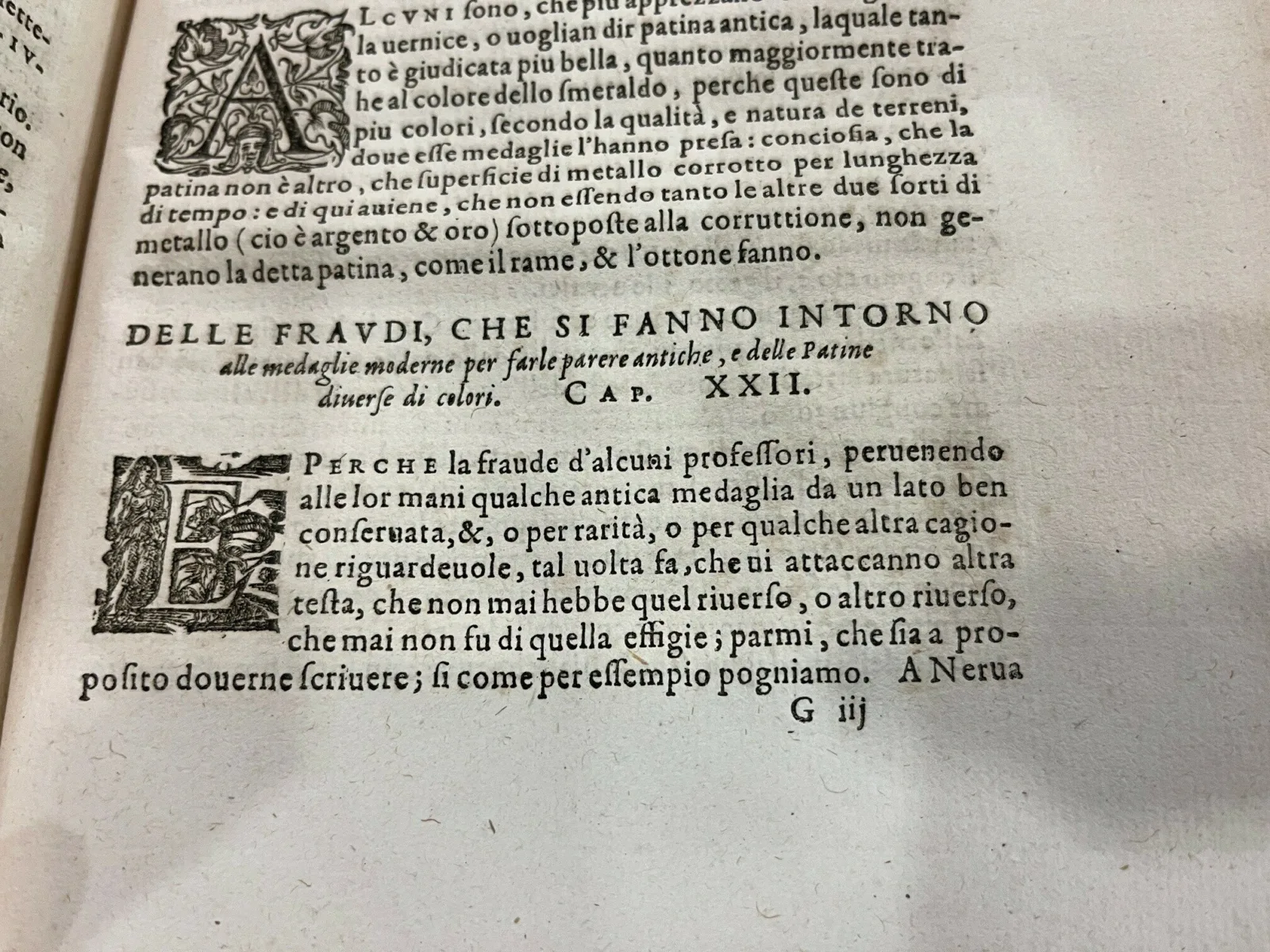

I think it is no coincidence that it is also in the sixteenth century when artist and antiquarian scholar Enea Vico published what many consider the first treatise on art forgery in 1555. Examining this book at the Newberry revealed that Vico used the Italian terms fraude (fraud) and inganno (deceit) to describe the deliberate and deceitful misrepresentation of ancient coins by living artists. However, he also applauded artists who worked nell'imitatione…per dimostrare la eccellenza loro, or “in imitation” of others as a way “to demonstrate their excellence” (67). For Vico, it was therefore the intention of the artist making the copy that mattered most. Artistic imitation as a form of practice and competition was acceptable and even applauded; however, profiting from the sale of manipulated or fake antiquities was condemned.

Yet reconstructing the intentions of early modern artists is often a tricky thing to do. Scholars are still unsure, for example, if the beautiful pseudo-antique coins made by Giovanni da Cavino, were sold as imitations or “authentic” antiquities. As these cases show, Greek and Roman coins were some of the most collected – and most copied – antiquities in the early modern era. Their small size made them easy to move and study, while depictions of emperors, monuments, and state emblems stamped on each side intrigued antiquarians and artists alike. The Newberry’s fantastic collection of early modern numismatic books has been instrumental in identifying examples of fake coins presented as authentic artifacts.

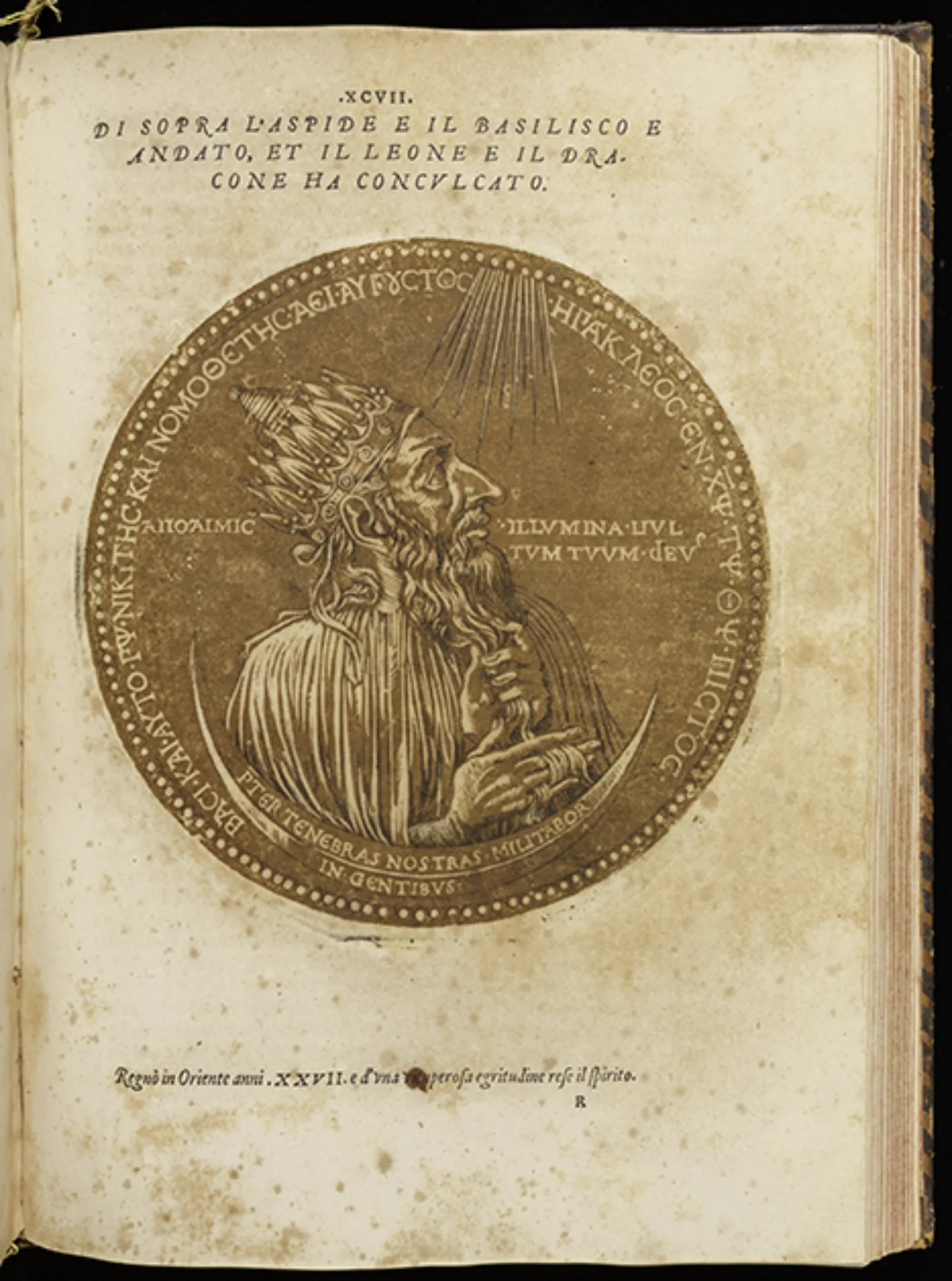

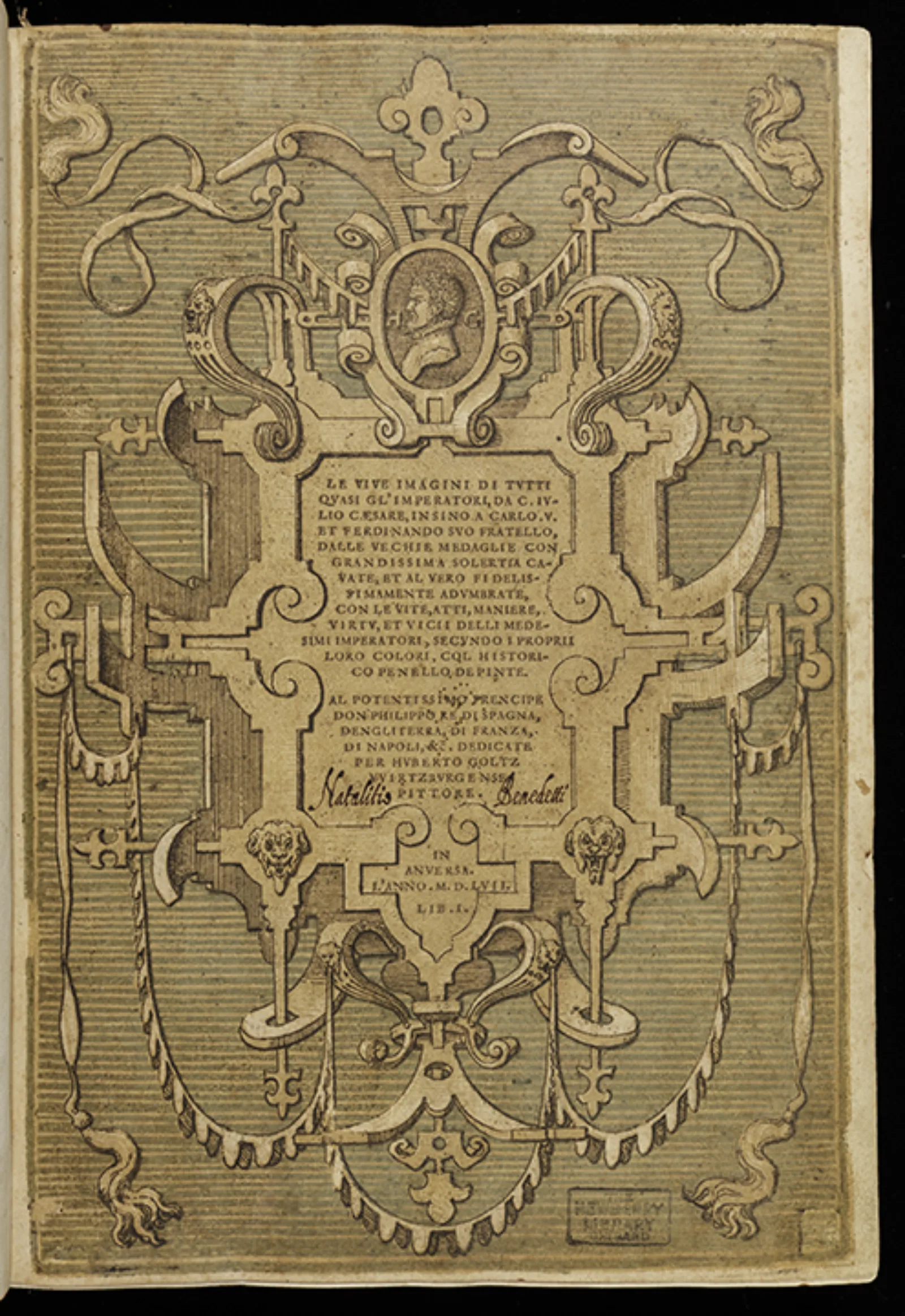

A key find for me was this 1557 numismatic book by artist and antiquarian Hubert Goltzius, who attempted to illustrate all the Roman emperors using coin-based portraits. Goltzius experimented with new printmaking technologies, including chiaroscuro woodcuts, to represent the high relief and patinated surfaces of the coins he studied during his three-year preparatory trip visiting Europe’s most acclaimed coin cabinets. A single coin is printed on each page. They remain visually striking today for their greatly enlarged size (17 cm in diameter), naturalistic color, and intricate detail and lettering.

Goltzius’s book was immediately successful and bought by many collectors who used it as a scholarly reference. Indeed, it was intended to operate, like the coins it so beautifully represented, as a store of present and future value. Yet the great irony of this book, as well as other antiquarian publications from the time, is that it included many objects now known to be early modern imitations or outright fakes. The portrait of Emperor Heraclius shown at the beginning of this post, for one, can be found on no ancient coin. It was instead based on an early fifteenth-century medal likely made on speculation for one of Europe’s richest collectors at the time, Jean duc de Berry. Goltzius himself likely believed the medal to be ancient. Scholars only began to identify these inauthentic interlopers in the seventeenth century, and “nummi goltziani” later became a by-word for fake ancient coins.

It is my hope that this research at the Newberry on “antiquarian speculation” will help us better understand how aesthetic and financial value inform one another. Like today’s artists, gallerists, and collectors, Vico and Goltzius were both participants and investors, in a way, in the sixteenth-century market for antiquities in a period marked by a heightened consciousness of the fine line between imitation and forgery. While restrictions regarding the movement of antiquities have developed substantially since the sixteenth century, the art trade remains one of the least regulated markets in the world. This seems like all the more reason to carefully consider debates about authenticity and value, intention and imitation, both in the early modern period and today.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Katherine Calvin is Assistant Professor of Art History at Kenyon College and a former National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow at the Newberry.