Renaissance self-medicating was a tricky business without antibiotics or vaccines. As with our pandemic, the biggest threats to humanity included exposure to airborne contagion (then vaguely understood as a noxious miasma, or bad air) and inconsistent medical advice.

The Black Death subsided around 1351 in Europe, but fear of contagion never really did; the plague resurfaced in Europe throughout the next few hundred years.

Apothecaries were the pharmacists of the Renaissance, privately doling out potions and ointments. But they soon had competition, as others began developing remedies for the plague––whether as herbal infusions or fragrant potpourri inhaled through a knotted cloth (or, by the seventeenth century, through the curved beaks of plague-doctor masks).

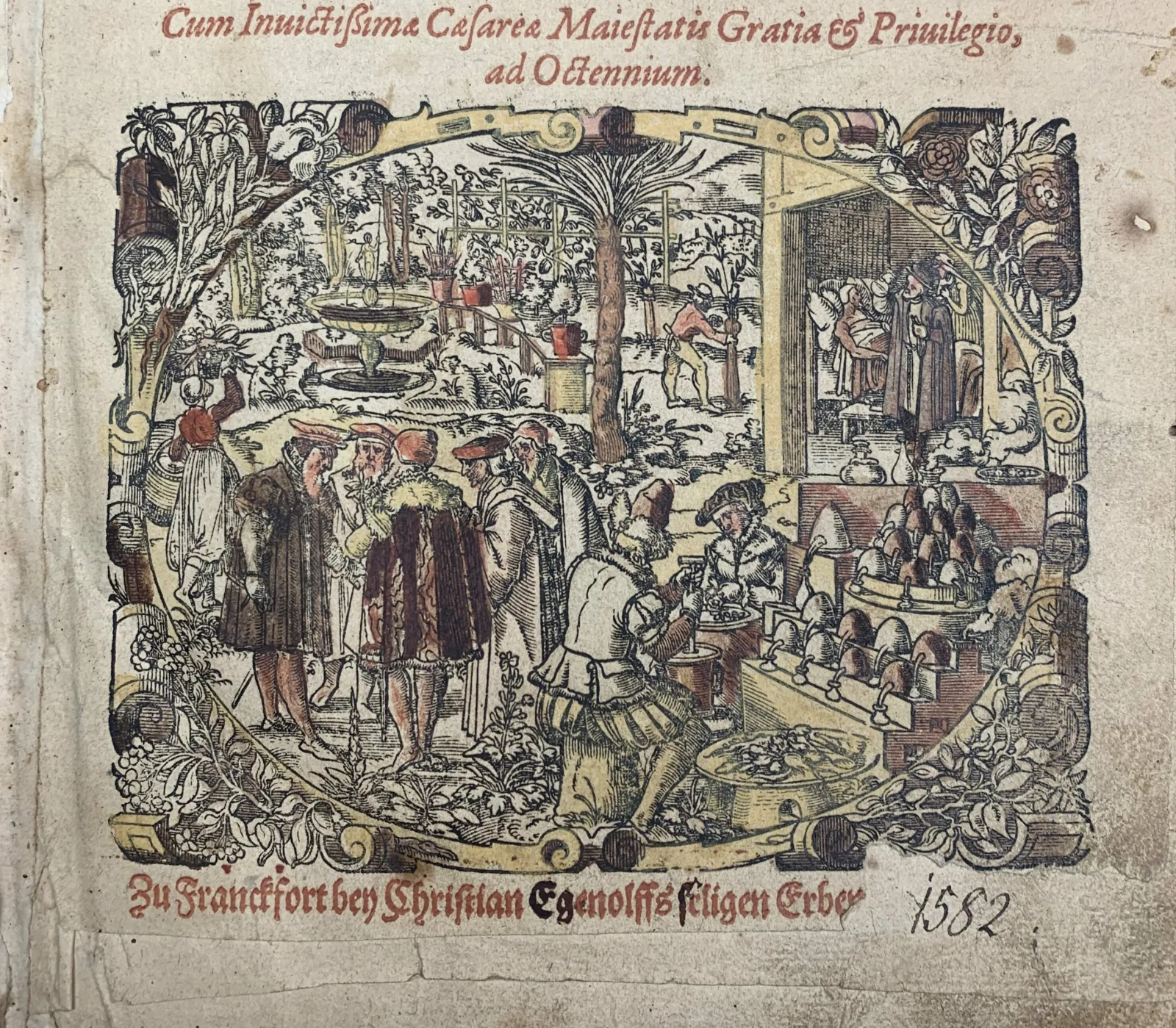

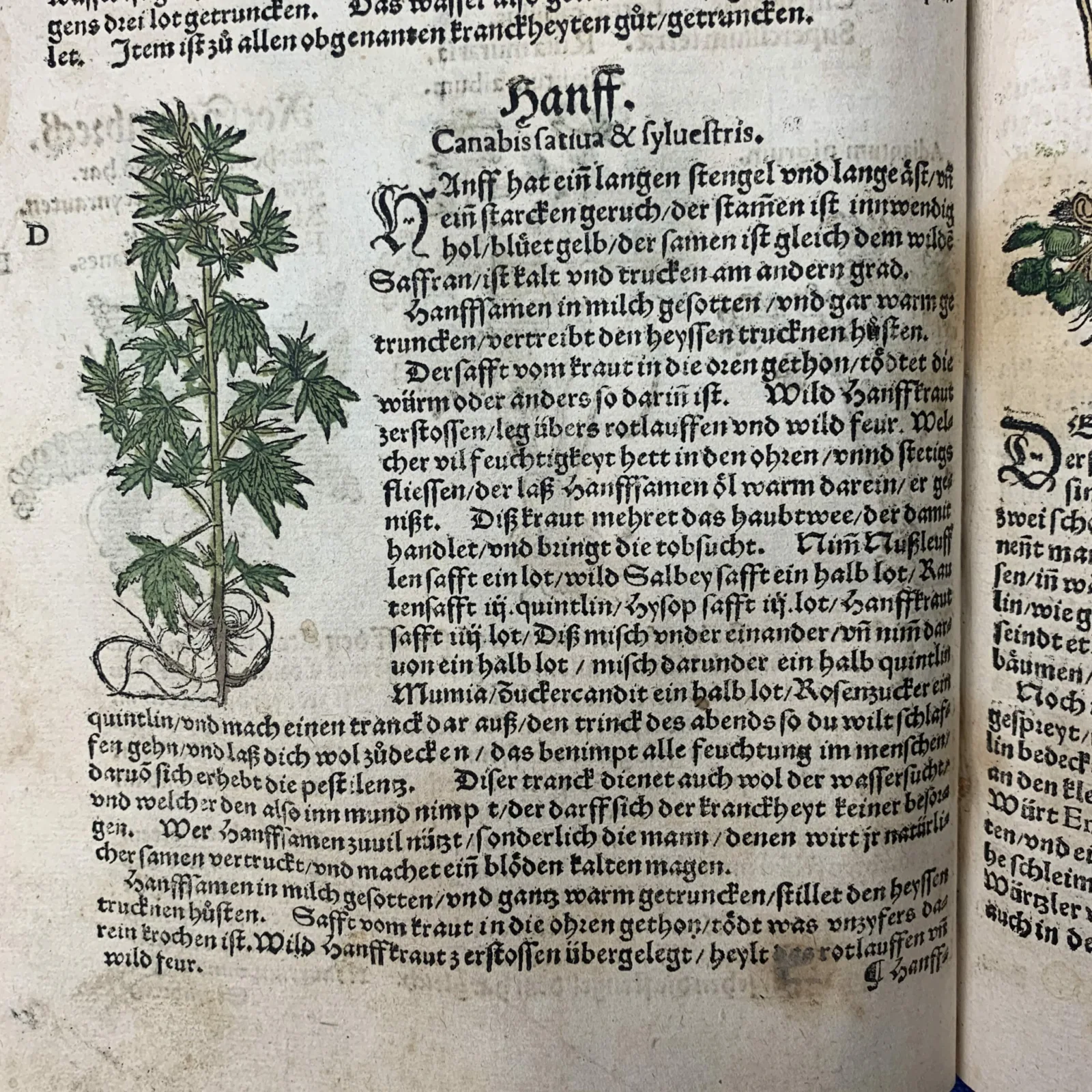

During the printed-book boom of the sixteenth century, herbals brimming with hand-colored plant woodcuts claimed to offer instructions for natural cures and preventative measures anyone could follow to protect themselves from the pestilence or plague. That is, anyone affluent enough to read and to gather the exotic ingredients.

The Newberry holds the 1546 and 1598 editions of the bestselling Kreuterbuch by German author, doctor, and botanist Adam Lonicer (1528-1586). Advantageously married to the daughter of his prolific publisher, Christian Egenolph, Lonicer was a German author, doctor, and botanist. His book on the myriad ways to distill plants into medicines long outlived him; by the expanded 1598 edition, its index reveals over thirty plants and other substances then assumed to have anti-plague power.

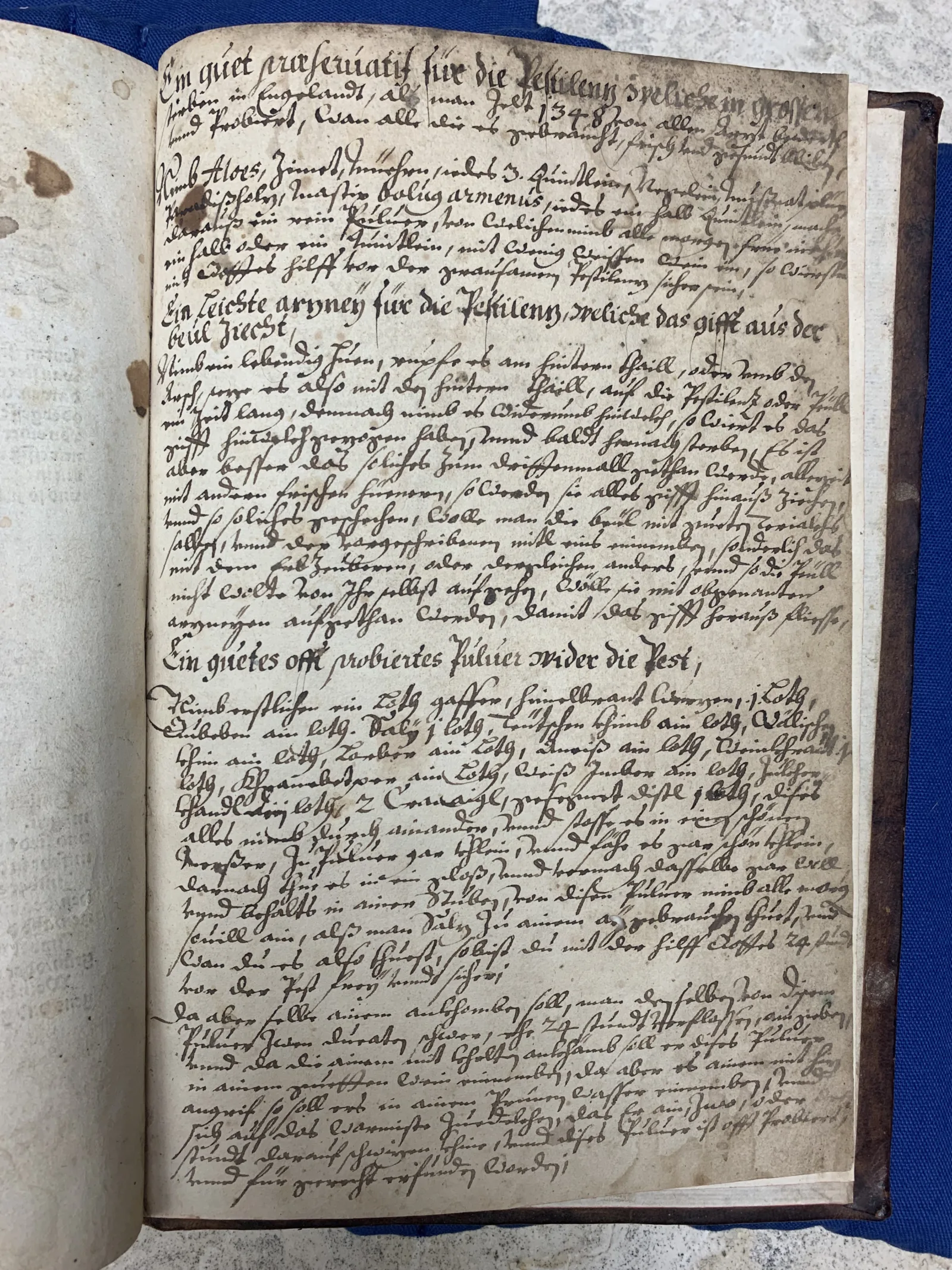

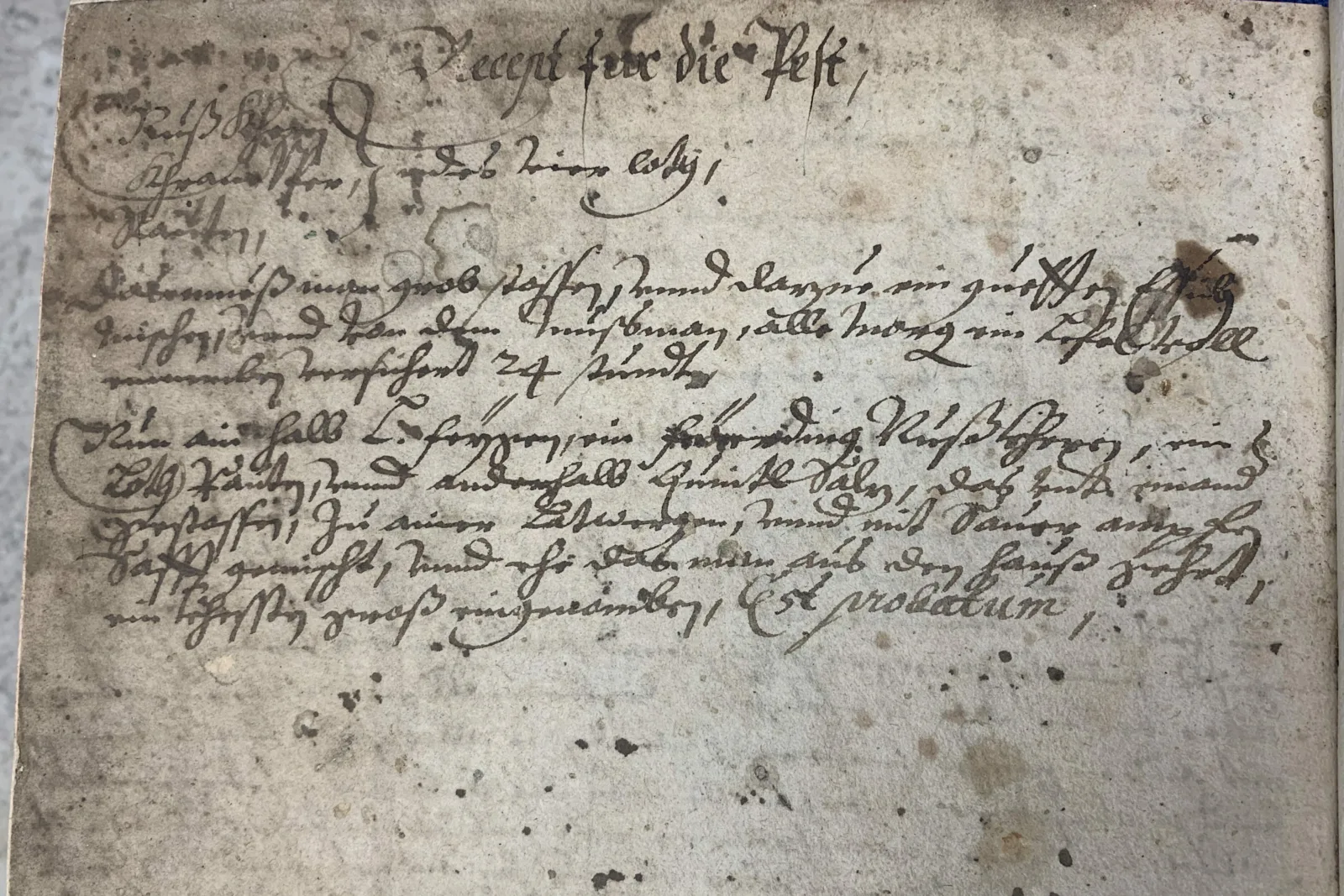

In addition, the 1546 edition includes four recipes hand-written in German and Latin at the back (unusually, they appear not to be verbatim copies of the text inside). Surprisingly modern in their similarity to today’s “one weird trick” clickbait, they suggest their compiler asked around for easy, tried-and-tested solutions. Whoever wrote the recipes clearly wanted to be prepared for the worst, to the best of their knowledge and ability.

Their notes are quite difficult to read, but the bold headlines stand out:

A good preservative for the Pestilence [used in England? Since 1348?]

An easy medication for the Pestilence, which draws the poison out of the boils.

A good, often attempted powder against the Plague.

Throughout the manuscript recipes, and in the book proper, the ingredients and measurements are exacting. They usually prescribe multiples of a loth (half ounce) or quint (eighth ounce), of, for instance, aloe or Armenian red clay, per draught.

In contrast to the harsh cleaning solutions of modernity, a few recipes seem plausibly therapeutic, and perhaps downright delicious: figs soaked in hyssop oil; powdered thistles in wine; pulverized lilies––and even the somewhat dubious mistletoe in warm beer.

An ostentatiously expensive-sounding concoction requires one ounce of distilled honey syrup mixed with aloes, red myrrh, saffron, and twenty barley grains, all rubbed together with a sheet of pure gold leaf.

Other ingredients are simply baffling: infusions of sulphur, and the milk (or blood) of goats, oxen, pigs, and badgers?! The most surprising recipe in the book however, boasts a now locally available main ingredient: Cannabis (Hanff/Hemp). Adding its juice to sage and hyssop extracts, sugar, and mumia (powdered human remains), among other substances, produces a relaxing night-time beverage that reportedly, once again, combats the plague.

Who annotated the Newberry book? An apothecary or amateur botanist? Did the owner actually make (and survive imbibing) any of these concoctions? Their final addition, a “Recipe for the Plague,” ends in the Latin phrase “Est probatum.” This means “it is proven,” so perhaps they really did.

About the Author

Suzanne Karr Schmidt is the George Amos Poole III Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at the Newberry Library.