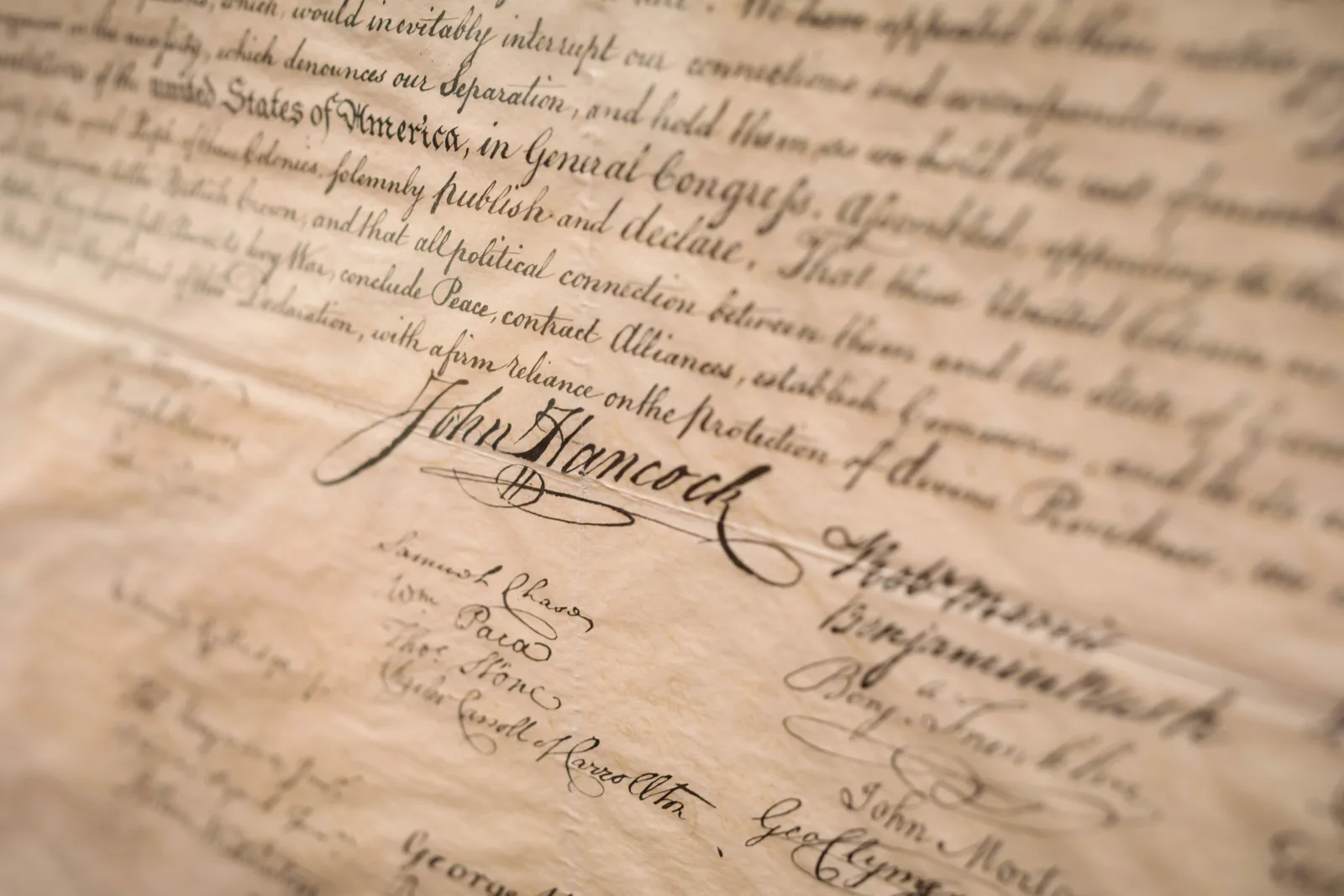

The Declaration of Independence was first printed as a text in newspapers in July 1776. But when most people think of the Declaration, they picture the manuscript version with its 56 signatures at the bottom, the most prominent being that of John Hancock.

The document was carefully copied out on parchment by a congressional scribe. By the early 19th century, however, it was beginning to show wear. Poor handling, storage, and conservation attempts had rendered some parts of the document (especially the signatures) almost illegible.

In 1820, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams commissioned a facsimile of the document from the Washington, DC engraver William J. Stone. While Stone was not the first person to engrave a copy of the Declaration, he was the first to make a full-size facsimile. His engraving is the closest representation of what the Declaration looked like at the time of its signing.

Although chemical processes that transferred ink from an original manuscript to a metal plate were in use in the early 19th century, it is more likely that Stone engraved the plate freehand. In doing so, he also had to engrave the text backwards on the plate, so that it printed out right-reading.

It took Stone three years to complete his work. He printed 200 copies of the Declaration on parchment, which were given to the surviving signers, as well as to current office holders (the copy belonging to Charles Carroll, the last signer to die, sold at auction for $4.42 million in 2021). Ten years later, Stone printed additional copies on thin paper for Peter Force’s nine-volume American Archives, a collection of documents from the American Revolution.

Stone’s engraving is not an exact replica of the Declaration. He made tiny changes throughout the document, perhaps because the original lettering was too eroded for him to see clearly or possibly to distinguish the engraving from the original manuscript. Or maybe he simply wanted to add his own mark to the work.

Today, we only know what the handwriting on the Declaration looked like in its original form thanks to Stone’s skill in engraving. When I look at the Stone engraving, I sometimes forget that it is engraved and marvel at the graceful handwriting and the power of John Hancock’s showy signature. Other times, I am astounded at the skill required of the engraver. How did he produce such fine lines that look as if they flowed from a quill pen? Is it the pen or the burin (a tool used in engraving) that created this document? Or is it both things at once?

The engraved Declaration has helped me to think about the complexities of creating—and reading—handwriting in print.

About the Author

Jill Gage is the Custodian of the Wing Foundation on the History of Printing. She is also the curator of A Show of Hands: Handwriting in the Age of Print. The exhibition is on view at the Newberry from September 9 - December 30, 2022.