The Newberry is one of Chicago’s most beautifully proportioned buildings—at least from certain vantage points.

The main structure (known as the “Cobb Building” after its architect) is a perfectly symmetrical arrangement, its central pavilion separated from two end pavilions on either side with recessed areas. The façade blends Renaissance and Romanesque styles, balancing rough-hewn stones at the building’s base with cleanly chiseled granite walls, groups of tall colonnettes, and arched windows at the upper levels.

The same cladding ornaments the sides of the building, yet at both the northeast and northwest corners, its symmetry is suddenly broken: the arches are only half-complete, while stone projections extend beyond the building’s walls. To the observer below, it seems almost as if the façade was abandoned mid-construction.

In fact, these “broken arches” were part of the original design of the Newberry building. They now serve as a vestige of a fascinating dispute that occurred at the library’s founding.

The Newberry was established in 1887, but a few years would pass before a permanent site for the library was agreed upon by trustees. During this time, there emerged a contentious debate over the architecture of the library that would be constructed on the site. The debate pitted the Newberry’s first librarian, Dr. William Frederick Poole, against the architect selected by trustees to design the building, Henry Ives Cobb.

At the time, many existing libraries were built on the “cathedral” model: a central, nave-like space served as the main reading room and was surrounded on all sides by towering book stacks, accessible at every level from attached balconies.

Poole had devoted much thought to library architecture and had a decidedly negative view of the cathedral model. It was inefficient, wasting large amounts of space and requiring librarians to travel great distances to retrieve requests. It was dangerous, allowing temperatures at upper stories to rise to levels harmful to books (especially leather bindings). What’s more, the single large reading room wasn’t conducive to serious study.

In its place, Poole proposed a rival design. Instead of a single reading room with walls of books rising around readers in successive tiers, Poole envisioned a number of smaller reading rooms, each devoted to a single subject and overseen by a single specialist librarian with ready access to (and knowledge of) the sub-collection held in his or her room. This “departmental” model would avoid the inefficiencies, dangers, and distractions of the cathedral model, while also encouraging intellectual exchange by gathering together in smaller spaces readers with similar interests.

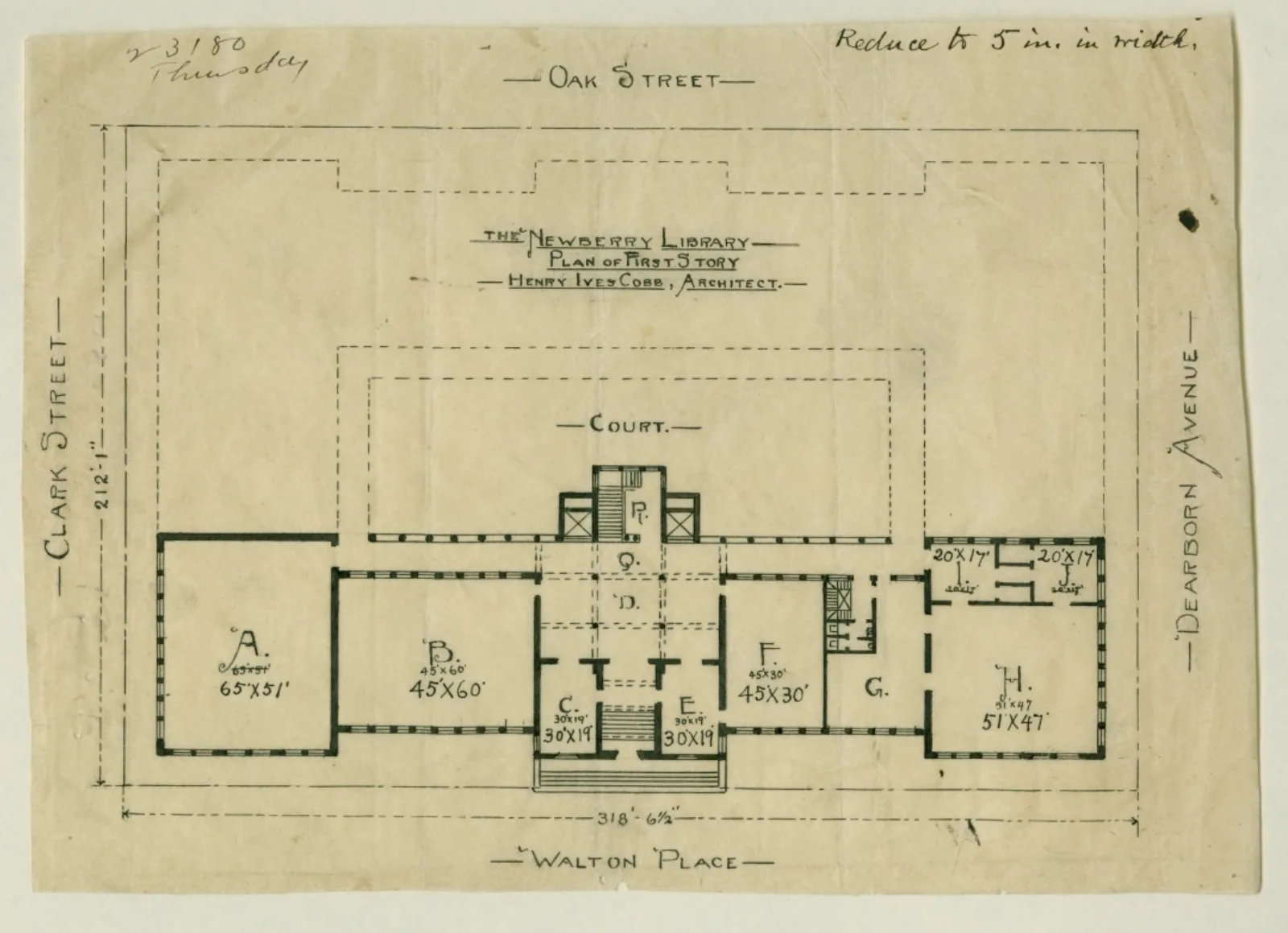

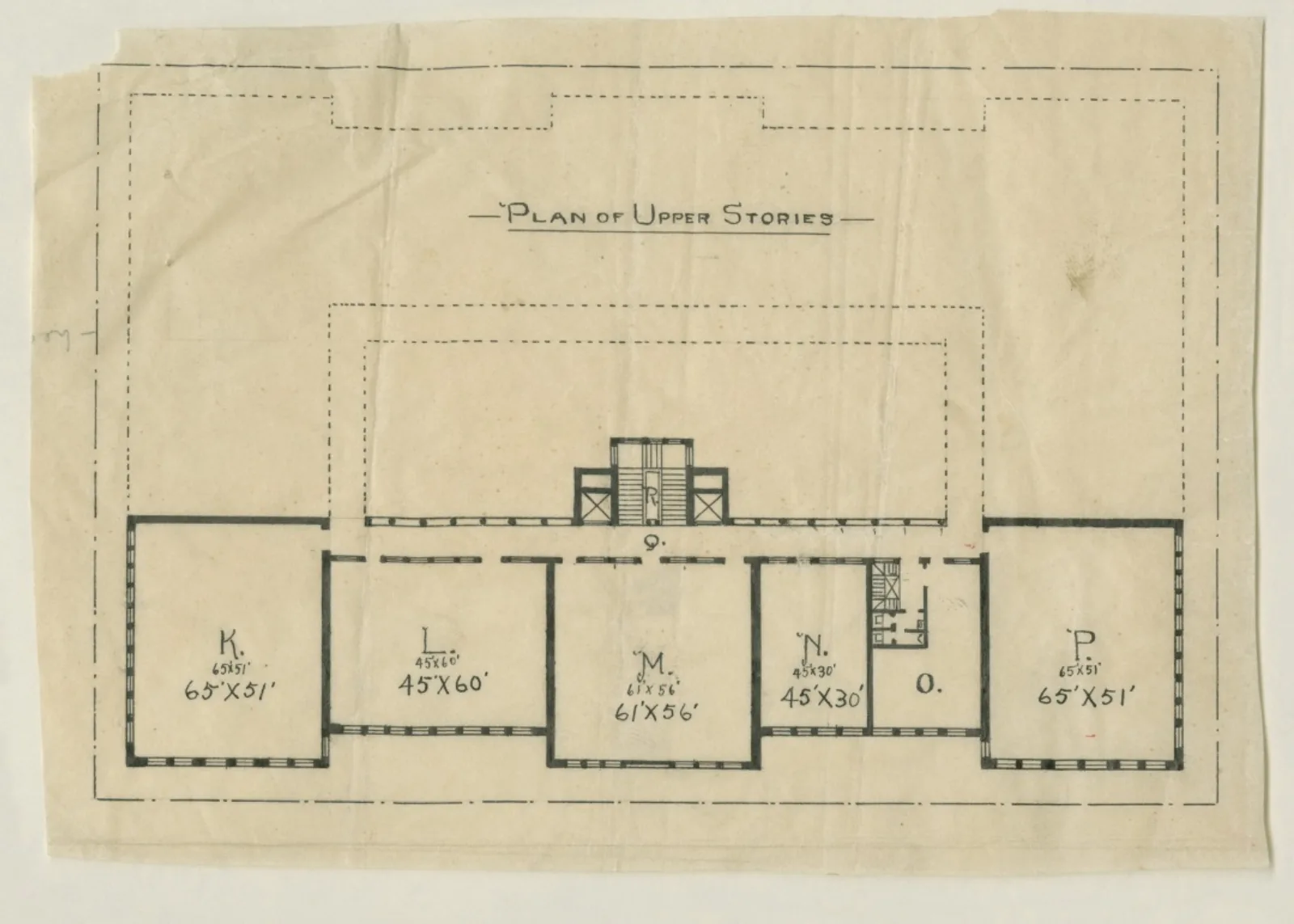

However, Poole was unable to put his ideas into practice without the right building. When he was named head librarian of the still-to-be-constructed Newberry, he realized that he would finally have the opportunity to realize his vision. He devoted himself at once to influencing the architectural plans for the library, proposing to trustees a four-story square building with a central court yard and 10 subject reading rooms to a floor.

To win over trustees worried about financing, he suggested that only the front section of the building need be constructed at first. The wings, he argued, could be added later, once the library’s subject holdings were large enough to require them.

Yet Poole’s plan was opposed by the young architect who had been hired to design the building, Henry Ives Cobb. Like Poole, Cobb rejected the cathedral model. However, in drafting his blueprint for the Newberry building, Cobb turned instead to a third design which was then gaining influence: the “stacks” model. Familiar to our users today, this model utilized a large reading room, like the cathedral plan, but separated books in a centralized stack—rather than a diffusion of book stacks across the library.

Like Poole’s department model, the stacks system avoided some of the practical problems of the cathedral design. However, the respective visions of Poole and Cobb clashed entirely when it came to the reading room. In his first plans submitted to trustees, Cobb embraced the stacks principle while making concessions to Poole, proposing an H-shaped building with a two-story general reading room, 10 subject reading rooms, and a stacks area consigned to a different wing, from which librarians could retrieve items requested by visitors.

But Poole would have none of it. Firing off a series of sharply worded letters to the trustees, Poole attacked Cobb’s plan, while Cobb defended his ideas in letters of his own. Soon, the dispute went public: an anonymous letter appeared in the Chicago Tribune voicing support for Poole’s proposal.

Whether due to public pressure, further internal maneuvering by Poole, or financial considerations, trustee support began to coalesce around the librarian’s approach. By January 1890, Poole felt confident that he had won the battle, writing in another letter to an acquaintance that “Mr. Cobb, the architect, has surrendered, and I am likely to have my ideas carried out.”

He was right—at least initially. Apparently concluding that opposition would be pointless, Cobb seems ultimately to have acceded to Poole’s wishes, drawing up a plan for the library that reflected Poole’s vision of a quadrangular building with a central courtyard and numerous reading rooms.

Thus, when workers finally broke ground a few months later, it was Poole’s building that began to take shape. Once the massive frontal wing was constructed, ornate cladding was applied to the front and two sides of the structure, but not to the back—for, it was expected, this wall would look out onto the courtyard once the library’s three additional wings were erected.

Likewise, the cladding broke off abruptly in the northeastern and northwestern corners, where the new wings were to be attached. In The Ideal Library of the Continent, Richard Brown (Vice President of the Newberry from 1972-1994) suggests that these strange projections would have been understood differently by both Poole and Cobb.

“For Poole, confident that future generations would follow his grand design, the projections pointed the way forward. For Cobb, disappointed not to have a completed building and responsible for an odd structure, richly ornamented granite on three sides with a plain brick and heavily windowed back, the message was probably more by way of apologia. He wished the public not to understand the building as completed” (59).

Yet though Poole’s vision won out in the short term, it was Cobb who would claim victory in the long run. As any passer-by can see, Poole’s additional wings were never erected. Ultimately, the library’s collections were not to be held in individual subject reading rooms. Instead, when after decades the Newberry’s holdings had grown to a size that necessitated expansion, it was a massive, climate-controlled stacks building that was added to the Cobb building.

About the Author

Matthew Clarke is Communications Coordinator at the Newberry.