Indigenous Chicago is more than just the latest exhibition in the Newberry’s Trienens Galleries: it’s a multifaceted collaboration between the Newberry Library, Chicago’s American Indian communities, and tribal nations with ancestral ties to Chicago. It highlights that Indigenous people have always been and will always be a part of Chicago history and allows visitors much-needed opportunities to reconceptualize Chicago as Indigenous land and space.

The Indigenous Chicago exhibition opened this past September; however, the wider project has been in the works since 2019. Rose Miron, co-curator of Indigenous Chicago and the Newberry’s recently-appointed Vice President for Research and Education, says that “the Indigenous Chicago project started with pretty informal conversations with Native community members about what their current priorities were, how folks were currently using the Newberry, and how the Newberry could support community ambitions.”

From these conversations, it became apparent that a primary community concern was the erasure of Indigenous history in Chicago, as well as the lack of knowledge of the contemporary Indigenous community present in Chicago. Fairly quickly, the Indigenous Chicago project came into view.

In January 2020, the Newberry hosted a community meal in coordination with the Chicago American Indian Community Collaborative, a delegation of organizations that serve the Native community in the city and its surrounding areas. At that meal, says Miron, “we first seriously put the question of a joint project out there. What do people think about this idea? What kind of resources would be useful if we were to create something, and what would you want it to look like? And we got a really resounding yes.”

At that meeting, community members and Newberry staff ultimately conceived of five core project components: an exhibition, an accompanying website with digital mapping, K-12 school curricula, an oral history project, and a series of public programs.

The Indigenous Chicago project is collaborative in its nature; each of its four co-directors come to the project with different expertise and specialties. As an historian, Miron worked on much of the earlier history the project covers, leading much of the research and digital mapping work. Meredith McCoy (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe descent), a former K–12 teacher and currently Assistant Professor in American Studies and History at Carleton College, specializes in 20th century history and Indigenous education; she led work on the project’s curricula initiatives. Analú María López (Huachichil/Xi’úi), the Ayer Librarian and Assistant Curator of American Indian and Indigenous Studies at the Newberry, brought her expertise of the Library’s decades-deep Indigenous collections to bear on many contextual aspects of the project, most especially the exhibition. Blaire Morseau, a member of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi and former Postdoctoral Fellow in the D’Arcy McNickle Center, crucially illuminated the portions of the project focused on more recent regional history.

The team also assembled an advisory group of about 25 people, created through nominations from community members. Care was taken to ensure the advisory group included significant representation from tribal nations. Several Indigenous scholars with relevant specialties also joined the advisory group, among them Doug Kiel (Oneida) and Michael Witgen (Red Cliff Ojibwe), both experts on Indigenous history in the Midwest across different time periods. The advisory group, which was divided into subcommittees overseeing each of the five project components, helped the project remain relevant and impactful: “this project isn’t about just checking off a box,” says Miron. “It’s about coming at these subjects with a lot of care, and being open to receive feedback in order to build something that is both evergreen and lasting.”

Naturally, for a project so manifold and comprehensive, audiences have many ways to find their way in. Much basic information repeats across the five components, which is intentional: the directors know that not everybody will engage with each component. The website, in particular, is designed to create connections across the project and serve as one hub for its every aspect.

The exhibition, of course, is a great way to get up close with dozens of objects relevant to Indigenous history across several centuries, including loans from partner organizations. As with any exhibition, the objects featured only hint at the complete picture attainable through deeper research in the Newberry’s collections.

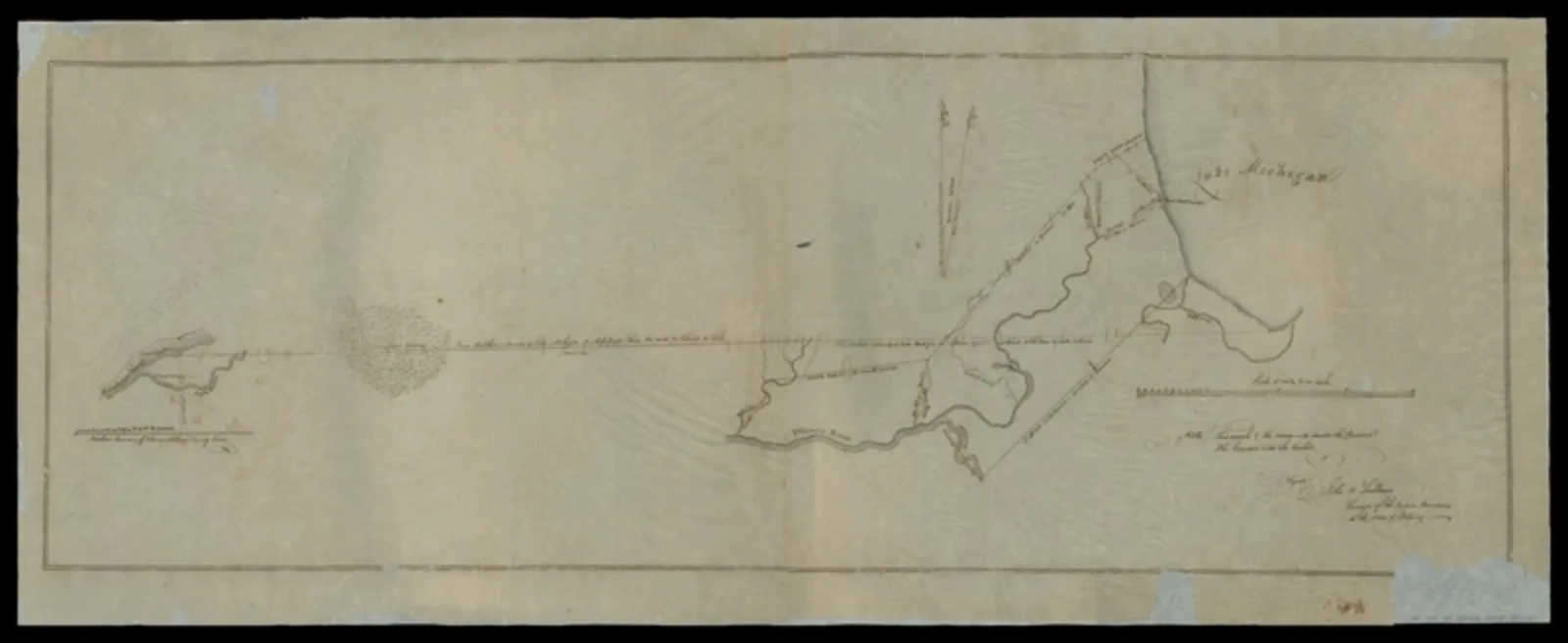

One item bumped from the exhibition (and for a good reason: the Newberry received a loan of the original 1816 Treaty of St. Louis from the National Archives) is the survey map for that Treaty. “That map is so useful in understanding this period in the city’s history,” says Miron, “because it really shows how much the desire to exploit the environmental factors of Chicago played a role in the removal of Native people from this land.” One objective of the 1816 Treaty of St. Louis was to facilitate canals, built later in the nineteenth century, that would activate Chicago as a center for industry and shipping. “That’s something that people don’t necessarily understand,” says Miron. “The growth of the city of Chicago, its role as a major industrial hub in the Midwest, was predicated on the forced removal of Native people.”

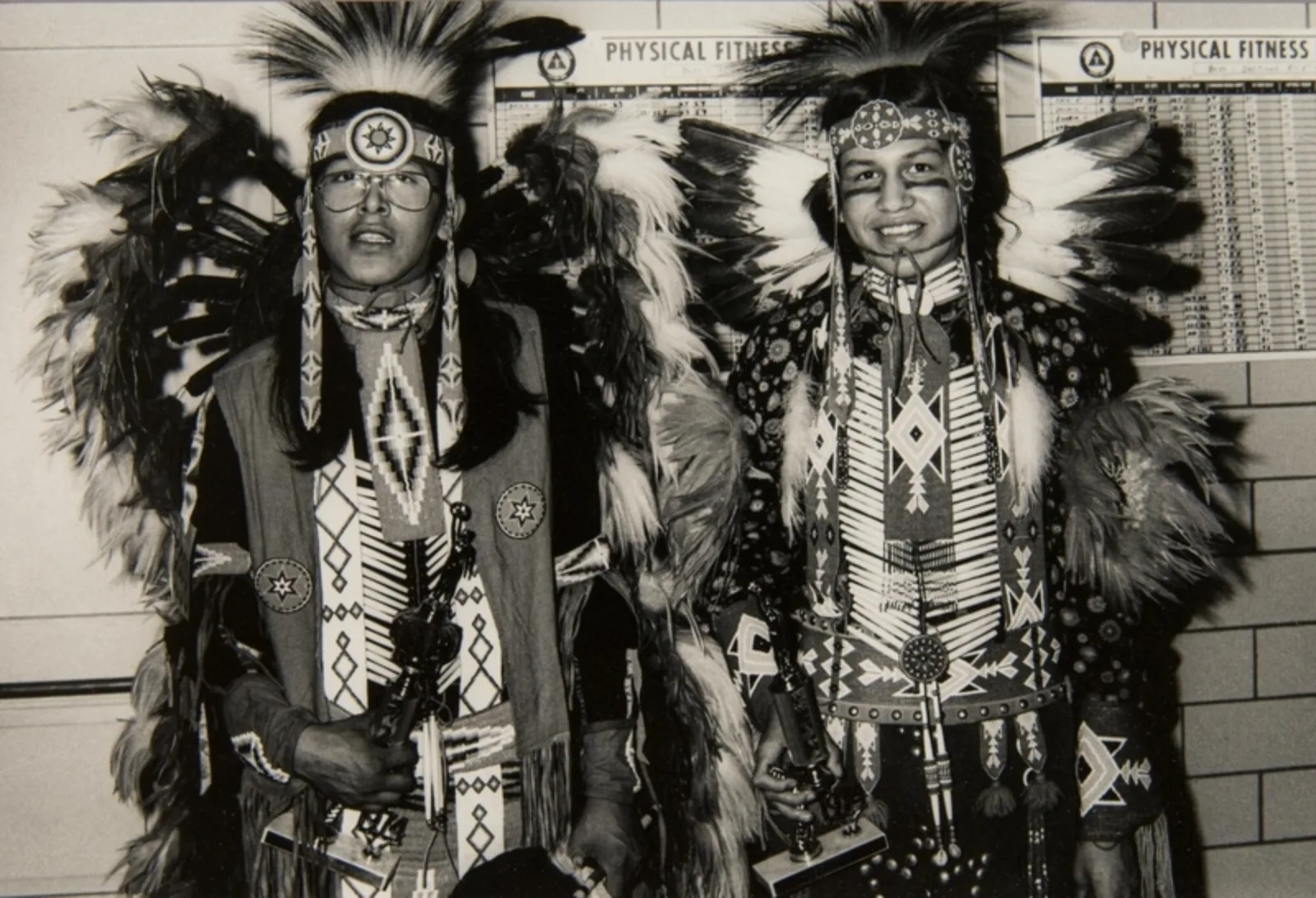

Indigenous Chicago is not, of course, the origin point for Native studies and collections at the Newberry; the Ayer Collection and the D’Arcy McNickle Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies both go back decades. In the 1980s, the Newberry hosted another important exhibition in collaboration with community members, entitled Seeing Indian in Chicago. As a result, the Newberry’s collections contain dozens of photographs of Native communities in the late 20th century. There are a small handful of these photos present in the exhibition, but the physical archive is much more comprehensive. A selection is also digitized, for those unable to visit our reading rooms.

The Indigenous Chicago exhibition is open at the Newberry until January 4, 2025. The project and website live on and serve as not only an educational resource, but a reminder that Chicago is, and always has been, a Native place.

This story is part of the Newberry’s Donor Digest, Holiday 2024. In this newsletter, we share with donors exciting stories of the work made possible by their generosity. Learn more about supporting the library and its programs.