Chirography, noun, a highfalutin word for handwriting. Popular in the 19th century.

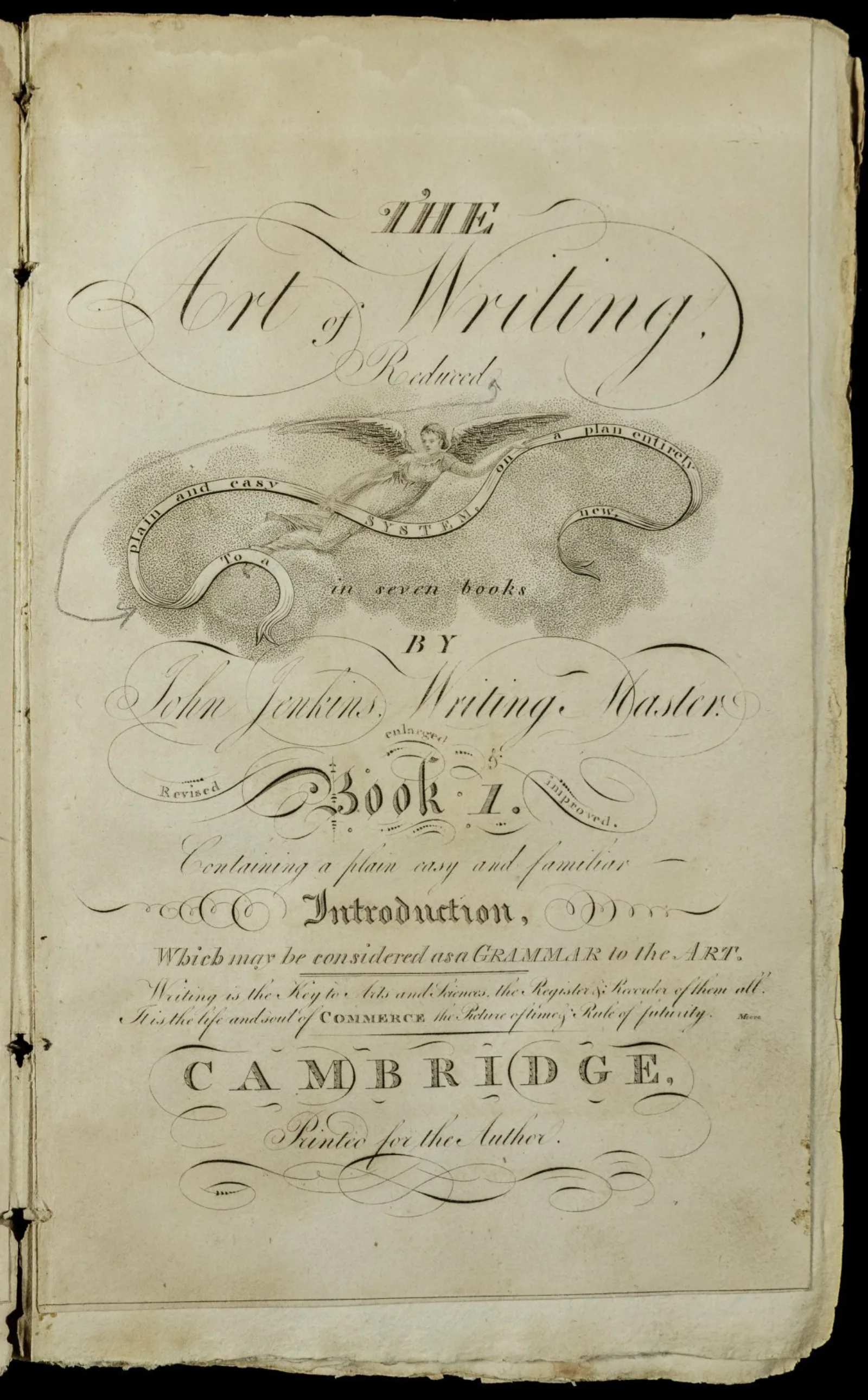

Among the items in A Show of Hands: Handwriting in the Age of Print are the 1791 and 1814 editions of John Jenkins's The Art of Writing. The first handwriting instruction manual published in the newly formed United States, The Art of Writing taught readers a novel way of mastering the standard 18th-century style of handwriting, round hand.

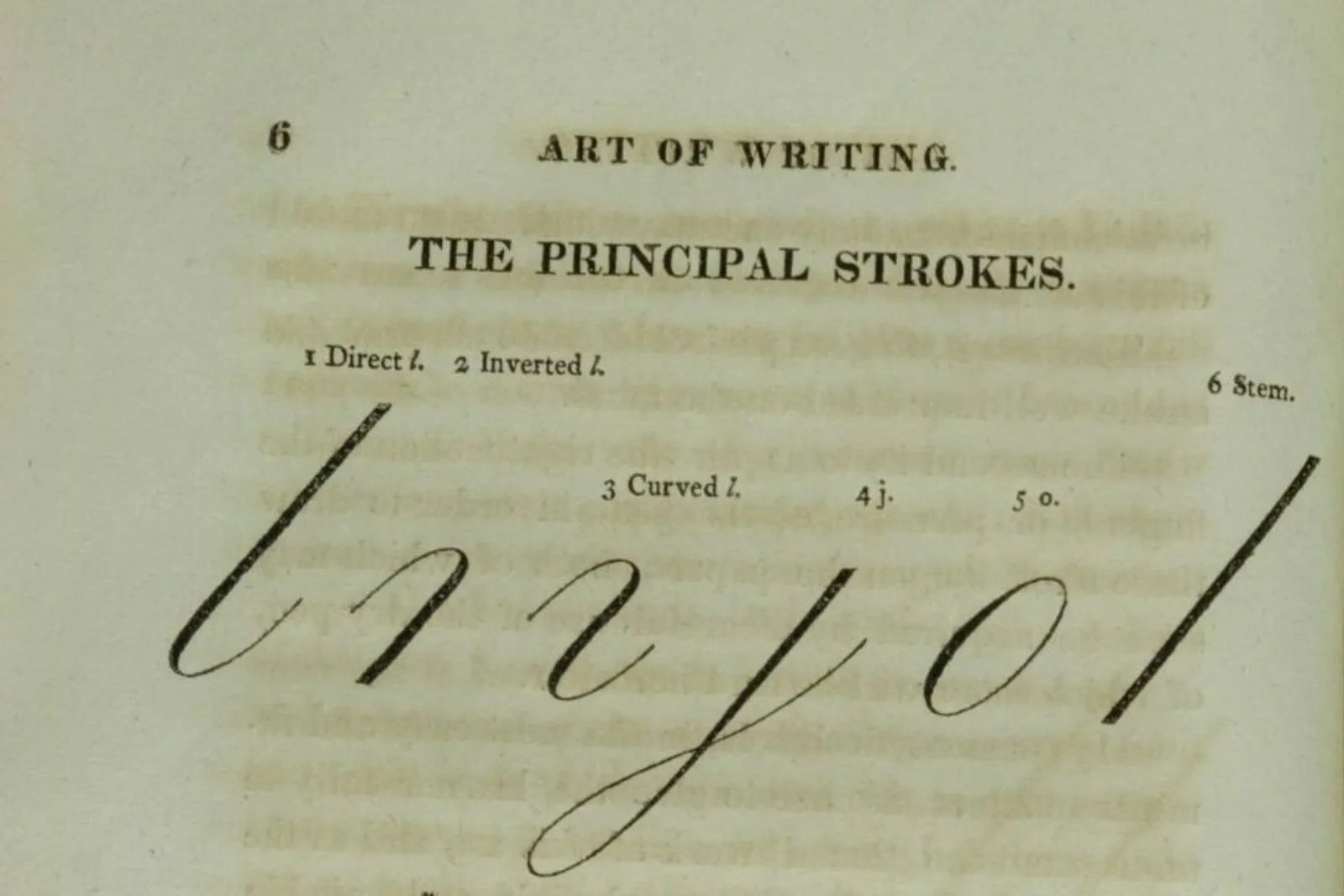

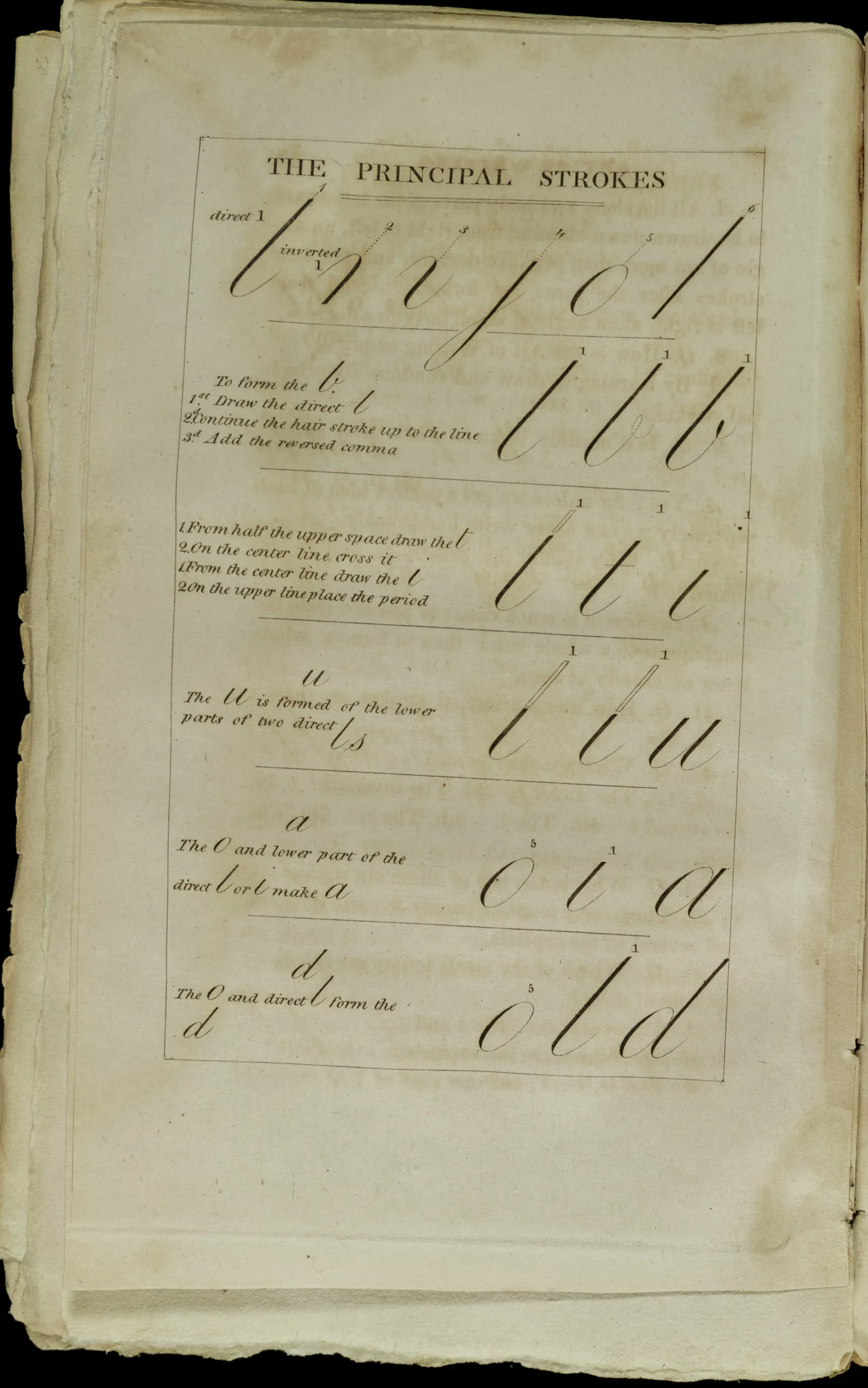

Instead of teaching students how to write each individual letter of the alphabet, Jenkins presented six basic shapes that could be used in different combinations to form letters. For example, joining an c to an l produces a d. (Jenkins used an identical method with different basic strokes for constructing capital letters.) In this approach, students learned to write letters not in alphabetical order but according to common shared strokes—a rather sensible way of learning how to write.

Jenkins's influence was felt not only in America, where nearly every handwriting manual printed up to the 1830s copied his approach, but also in England. In 1814, Joseph Carstairs published A New System of Teaching the Art of Writing in which he increased Jenkins's six basic strokes to 17. By the late 1820s, Carstairs's system had been translated into German, Italian, and French, and, in 1830, was introduced in America by the patriotically named Benjamin Franklin Foster in his Practical Penmanship, being a Development of the Carstairian System.

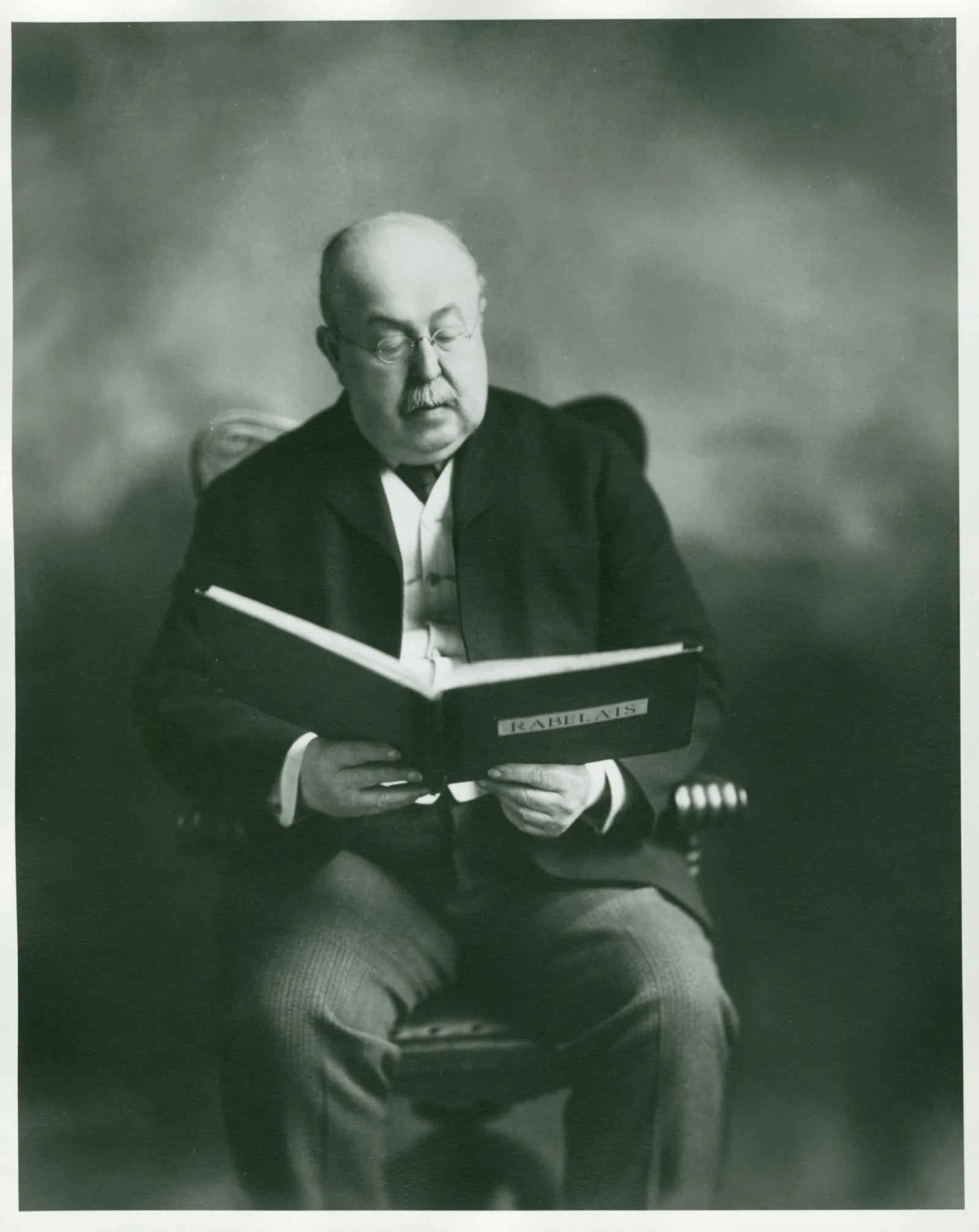

John Mansir Wing (1844-1916), the eponymous benefactor of the Newberry Library's collection on the history of printing and the book, was born in rural upstate New York and undoubtedly learned to write following the methods developed by Jenkins and Carstairs (via Foster). That he was, however, not a very adept pupil is reflected in the diaries he kept between 1858 and 1866.

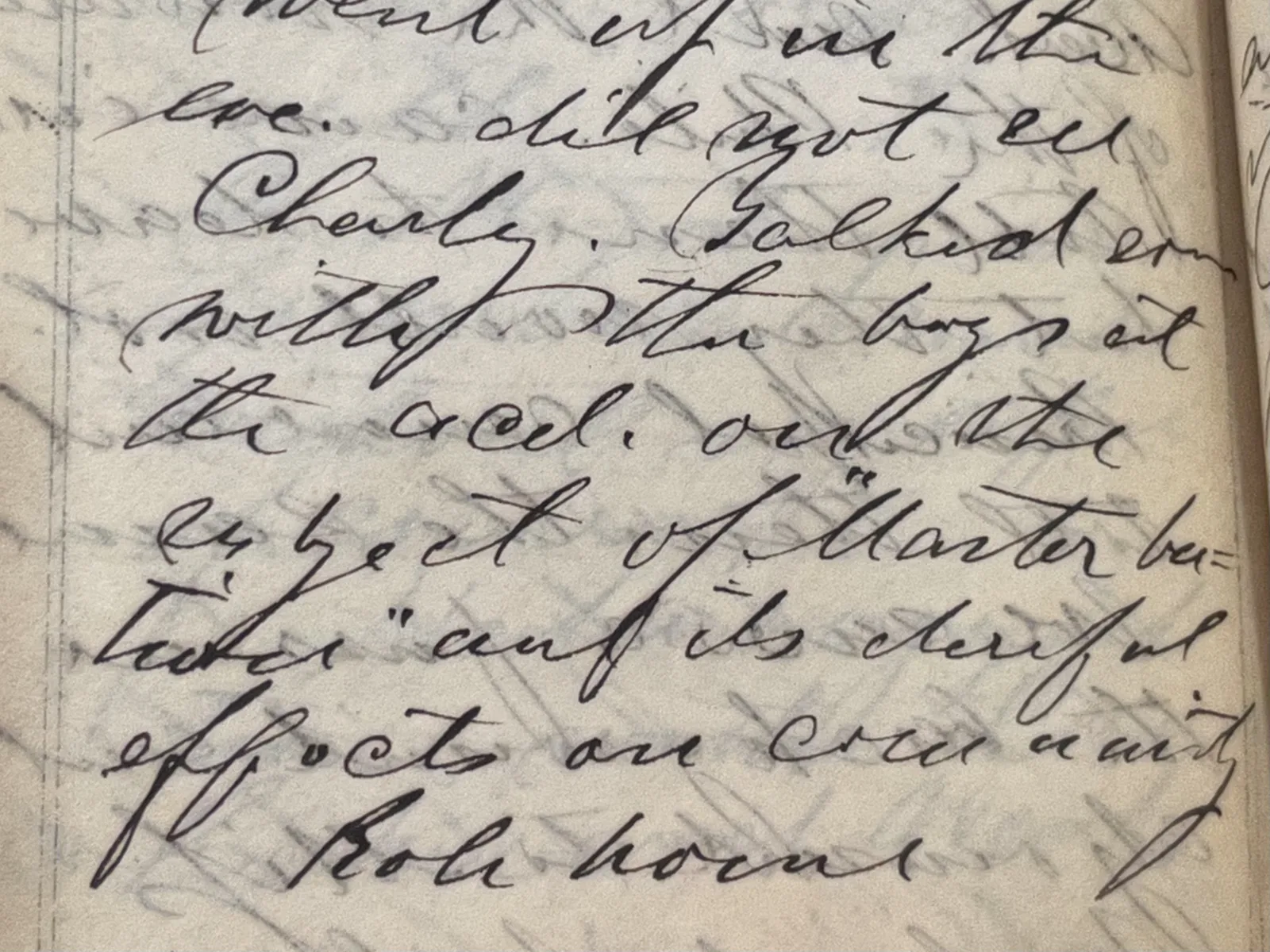

His chirography can be difficult to impossible to read, with individual letters sometimes exploding into their component parts derived from Jenkins. Often, the reader must rely on deciphering a few letters and, from the context, fill in the rest of the word.

I found myself in that position several years ago when I transcribed Wing’s diaries. One entry in particular led me to burst out laughing in the quiet of the Newberry’s Special Collections Reading Room.

Wing’s diary from 1860 was a combination diary and notebook. Although each page was devoted to a single day, Wing sometimes ignored this format and wrote about feelings and events over several pages. The teenage Wing was quite open about romantic crushes on both male and female friends, and was especially ardent when writing about Charles D. Gurley, aka Cuddy aka Charley:

My Dear Friend C K [sic] Gurley came home with me from the reading society and stayed all night. Oh! It was a night of bliss long to be remembered by me. And never did I enjoy myself better than I do this winter at school with my dear Gurly [sic], and so many “fair ones” to go with, wish that I could have kept a diary of the many events.

Wing also liked sharing a bed with his chums:

Went up to Centreville with him [Lon Kenyon] and had a very, very good time slept with him some little while alone, and had a very good “cuddling,” but soon Old Jim came and 3 in a bed were too much for me.

After deciphering these entries, it became easy to misread his scribbling. This is how I initially transcribed part of the entry from September 28:

Went up in the eve. did not see Charley. Talked some with the boys at the acd. [academy] on the subject of “Master bation” [sic] and its cheerful effects on [the] comunity [sic] Rode home.

After a good giggle, I eventually realized that Wing had not written ch but a rather messy d (c + l). The word wasn't "cheerful" but “direful"!

While a bit of an oxymoron, paleography can include the decipherment of modern handwriting, as reading Wing's scrawl demonstrates. An awareness of how handwriting was taught is helpful.

As I write this, The New York Times has put out a call for examples of messy penmanship. Perhaps some will justify their cacography (bad handwriting) by saying their hand can't keep up with their thoughts.

In Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen had this to say about that:

. . . you are really proud of your defects in writing, because you consider them as proceeding from a rapidity of thought and carelessness of execution, which, if not estimable, you think at least highly interesting. The power of doing anything with quickness is always prized much by the possessor, and often without any attention to the imperfection of the performance. . .

When you go through A Show of Hands, keep in mind that handwriting was once thought of as more than just a visual means of communication. It was, as the title of Jenkins's book indicates, considered an art appealing to the eye as well as the mind.

About the Author

Robert Williams is the editor of The Chicago Diaries of John M. Wing: 1865-1866, and a Newberry Library Scholar in Residence studying 19th-century chirographic pedagogy.