On August 22, 1945, Col. L.B. Chambers of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, wrote to the Chicago postcard publisher Curt Teich:

“There was a war to win on December 7, 1941, and you helped win it. You, who ran food labels, window displays, twenty-four sheet posters, and hundreds of other lithographed products, were called upon to produce maps for war. To most of you a map was gas station issue, but you learned about military maps – not only learned but produced them by the thousands.”

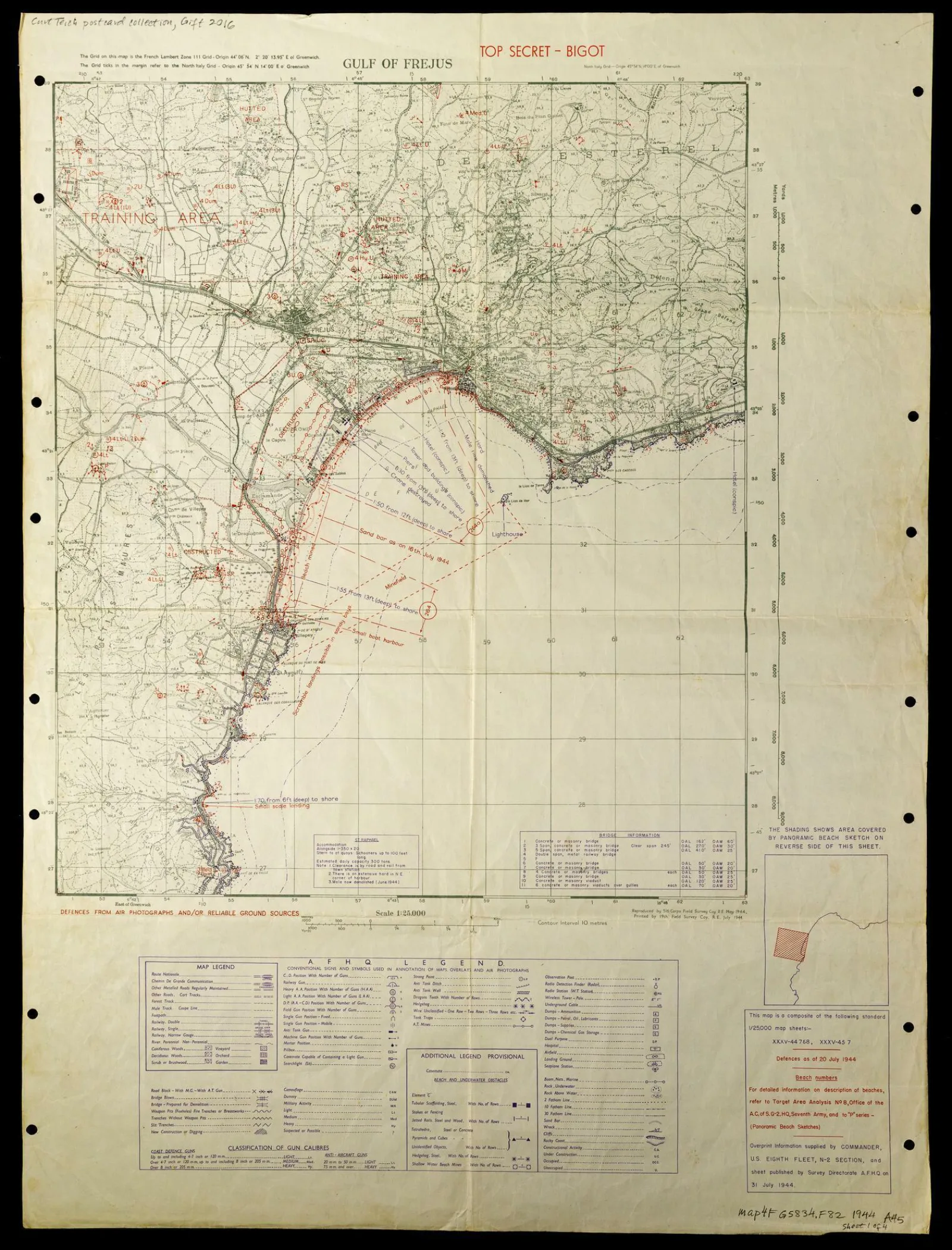

Less than a month later, on September 12, Lt. Col. Frederick W. Mast, also of the Corps of Engineers, sent his own letter of thanks to Teich, noting that from January 1944 to the end of the war, that Teich’s company had produced 3,160,000 maps for the U.S. Army. Alas, only one of these, a map prepared for the invasion of Frejus, France in August 1944, is held by the Newberry. A reproduction of that map is now on display in our exhibition, Making an Impression: Immigrant Printing in Chicago.

The fact that the German-born Teich (1877-1974), who emigrated to Chicago in 1895, would be asked to do work for the U.S. Army during World War II is remarkable on its own, but what is even more extraordinary is that the maps that Teich’s company produced were the highest level of top-secret government documents, as evidenced by the letters “BIGOT” at the top of the map. BIGOT was a security classification beyond Top Secret. Some sources suggest that it was an acronym for “British Invasion of German Occupied Territory;” others, that it was an inversion of “To Gib,” the code stamped on the papers of officers headed to Gibraltar in advance of the 1942 North Africa invasion. While the maps include basic topographic details, they also identify turreted weapons, minefields, roadblocks, communication trenches, tank traps, beach and underwater obstacles, and more. While millions of these top-secret maps were required (about 14 million maps were used for the D-Day invasions alone), some were decoy maps with purposely incorrect information. These decoy maps were a matter of security so that no sensitive information could be leaked.

Why Teich & Co.? Teich was well-situated to produce these maps because the company had the most up-to-date color printing equipment as well as in-house workers who specialized in airbrush and colorization work and could quickly produce the minutely detailed, large-scale color maps. In an oral history, airbrush artist Nitza Deamantopulos (1908-91) describes working on the maps while hundreds of other workers at the factory continued their own work completely unaware of what was being printed one floor below them.

Somewhat ironically, the Army cartographers who created invasion maps used postcards of the French landscape as source material, along with 19th-century charts and low-level aerial photos of the coast. It’s a story, then, that comes full-circle, with postcards and immigrant Chicago printers at its center.

Making an Impression: Immigrant Printing in Chicago runs between now and March 29, 2025, in the Newberry's Hanson Gallery.