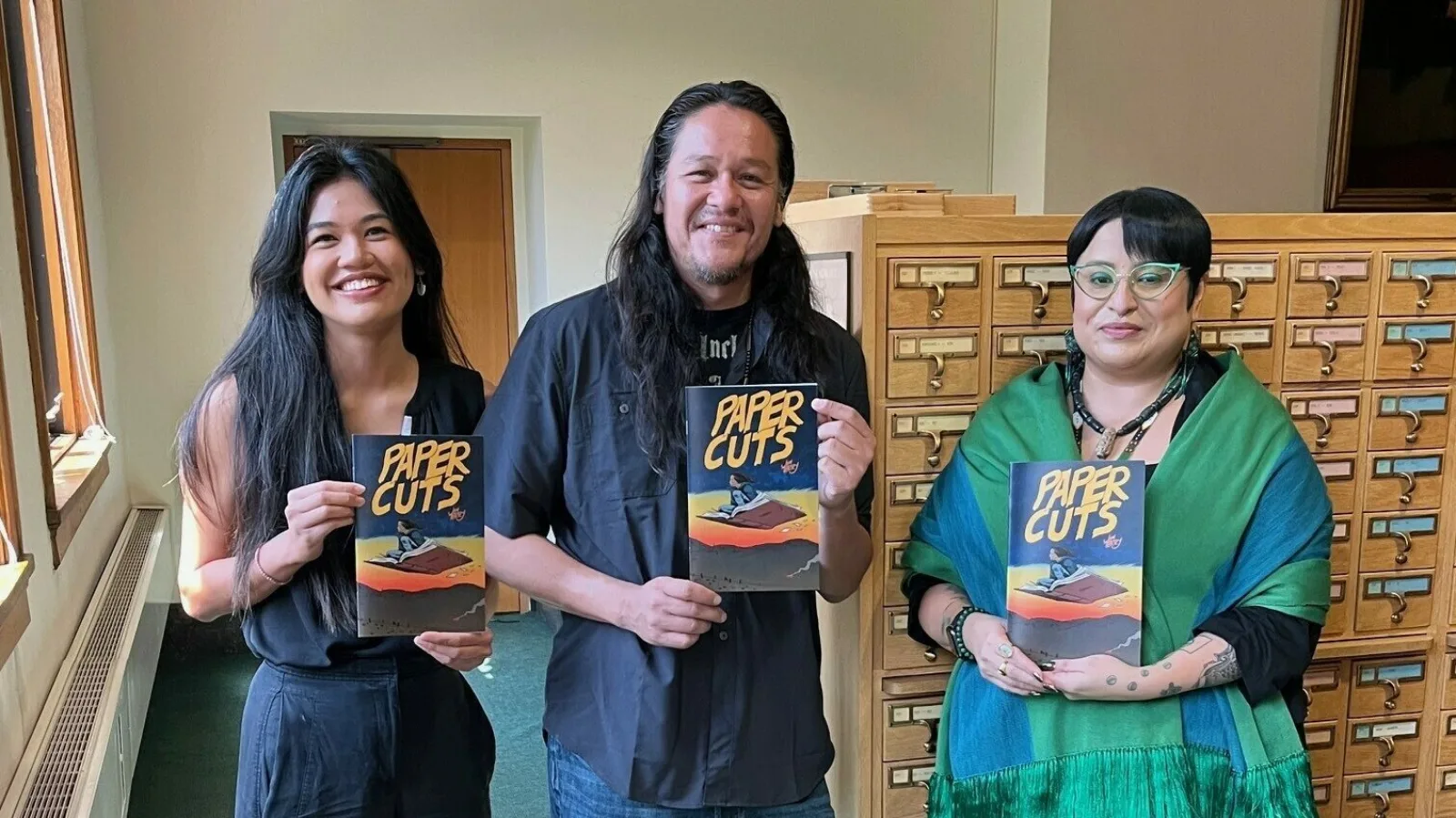

Jim Terry (Ho-Chunk) is a Chicago comic book artist whose memoir Come Home, Indio was a finalist for the LA Times Book Prize. Jim recently was an artist-in-residence at the Newberry, and his new graphic novel, Paper Cuts, commissioned for Indigenous Chicago, reflects his personal journey through the library’s collections and its vast holdings in American Indian and Indigenous Studies. He joined us for a Q&A.

NL: Did you have much research experience before coming to the Newberry?

JT: I’ve never been a researcher, most of my storytelling is fantastical. I am interested in history and read on my own quite a bit. Being a reader is different than being a researcher - I would get engrossed and spend half a day reading something that had nothing to do with why I was there.

I never had an experience like this residency. Even in school, I was really bad in taking the time to dig deep. As I got older, I was really interested in what was happening and had to teach myself along the way how to weed through this stuff.

NL: There’s a section of the book where you reflect on the research experience at the Newberry and all the emotions including frustration that it caused. Can you talk about your experience with the collections?

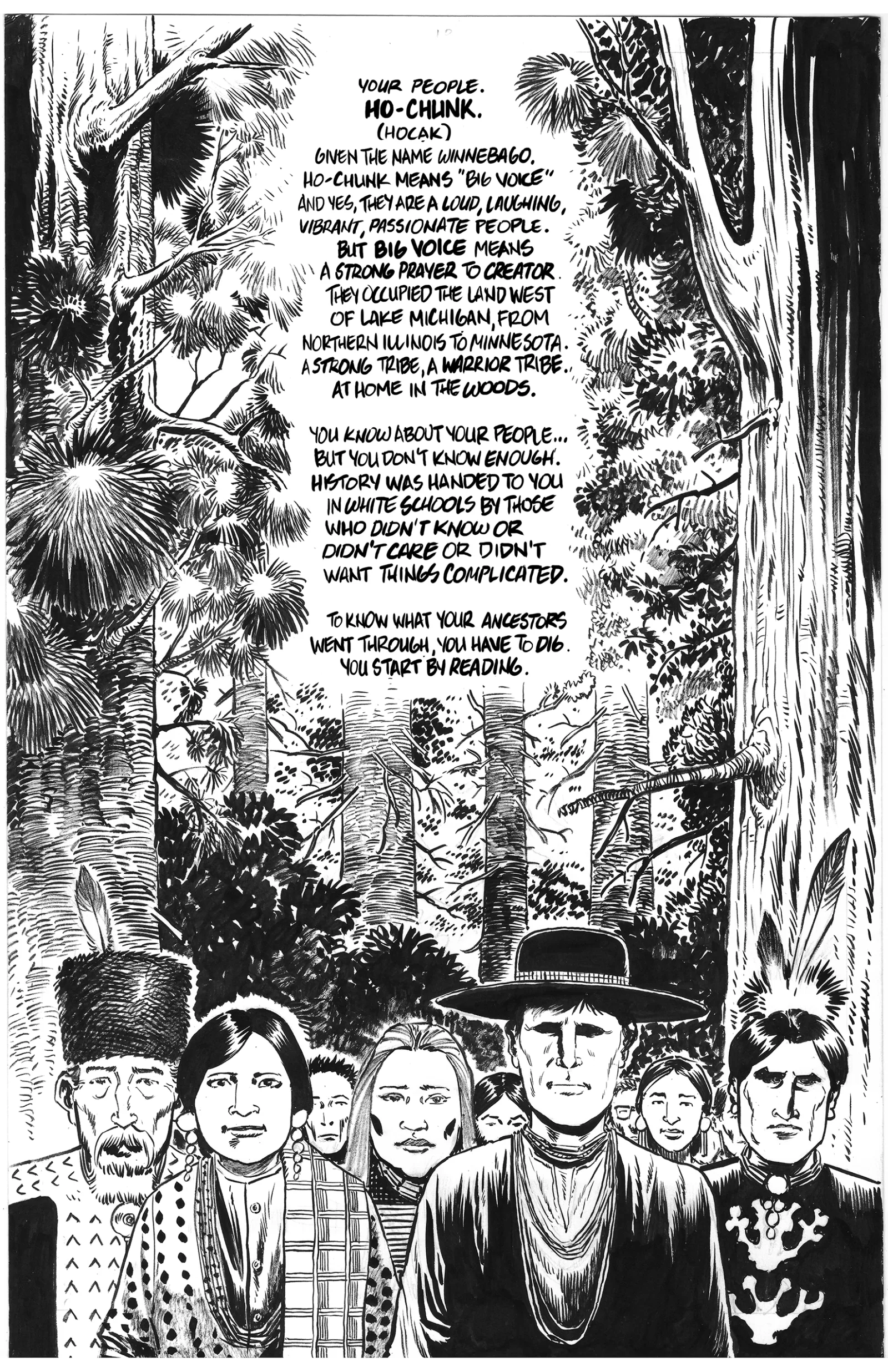

JT: I’m a big horror movie buff and love spooky things. [When I arrived at the Newberry] I thought I’d read all about different legends and supernatural stories, and I realized that was too difficult to find. The stories, without them being explained, come off as really obtuse a lot of times. I had to re-direct myself a month or two in and decided I’m just going to read about Ho-Chunks because I didn’t know enough about my own people.

I started reading more, and it was overwhelming. One was the strange way much of it was presented, you start to wonder who is telling the story and what are their motives. Sometimes the author’s voice would seep in and their beliefs and how they felt about Natives were sometimes... not great. Other times they were well-intentioned but kind of cringey. That started to get to me. I began to look at the city and my place in it, and there were realizations that made me so angry, I couldn't put them in [Paper Cuts].

I spoke with someone around that time who was buying land in Wisconsin, just for a place "to get away." I had a visceral reaction because that’s where my people are from, and we were kicked off of [the land]. That’s not something that non-Native people think about, a connection to this land, and it’s hard to explain without seeming like a real drag. But three or four generations ago, we were living there, that’s where we are from.

NL: You mentioned not knowing about your people. Were you in touch with your Native heritage as a young person?

JT: It came later. The culture has been handicapped by the colonial thing. My grandmother was in a residential school where she was taught to be Catholic. My mother went to a similar school. We weren’t taught the traditional ways, we were taught to survive in this world. It wasn’t until my late 20s that I started reading about my people and becoming more involved in any way. I started looking at it as something not to be ashamed of, not to hide. When I was growing up, it was something not to talk about because you didn’t want to... suffer.

NL: There’s a section of the book where you go back to Wisconsin to re-visit an area of the Dells that you’d visited in childhood. It seems your perspective of that area has evolved quite a bit through the years. Can you tell us about that?

JT: I’m from the Chicago suburbs, but we spent summers in Wisconsin. The area we visited has been owned by a boating company since before my time. It’s sacred land, and when we were young there was an agreement with [the company], a business agreement. We were part of a tourist attraction called the Stand Rock Indian Ceremony where they would boat people in to watch the show, traditional dances and songs. The Ceremony has been over for decades - but back then, in the daytime we could go down and swim, explore, walk around. Now they’ve fenced it all off and flexed their ownership. They still do the boat tours and the souvenir shops, but we can’t walk around freely anymore. There are cameras and dogs and fences and all that good stuff.

NL: It sounds like the legacy of Native boarding schools has really hit home for you because of the experiences of your mother and grandmother.

JT: It wasn’t until they started unearthing the unmarked graves in Canada a few years ago that I realized it was one generation ago, for me. This really wasn’t that long ago, at all. It was my mom, and I’m a direct result of what they did [at boarding schools]. She came out of there, and they did not teach them the old ways. It’s up to us now, and further generations, to start piecing back together what was destroyed or attempted to be destroyed. It’s right there. It was yesterday.

Jim Terry will be joined by Camille “Katahtu’ntha” Billie (Oneida, Diné) and Jason Wesaw (Pokagon Band of Potawatomi) on October 10 at the Newberry for a free Public Program, "Indigenous Artists and the Archives." The event takes place at 6pm and is available in-person and online. Learn more and register here.