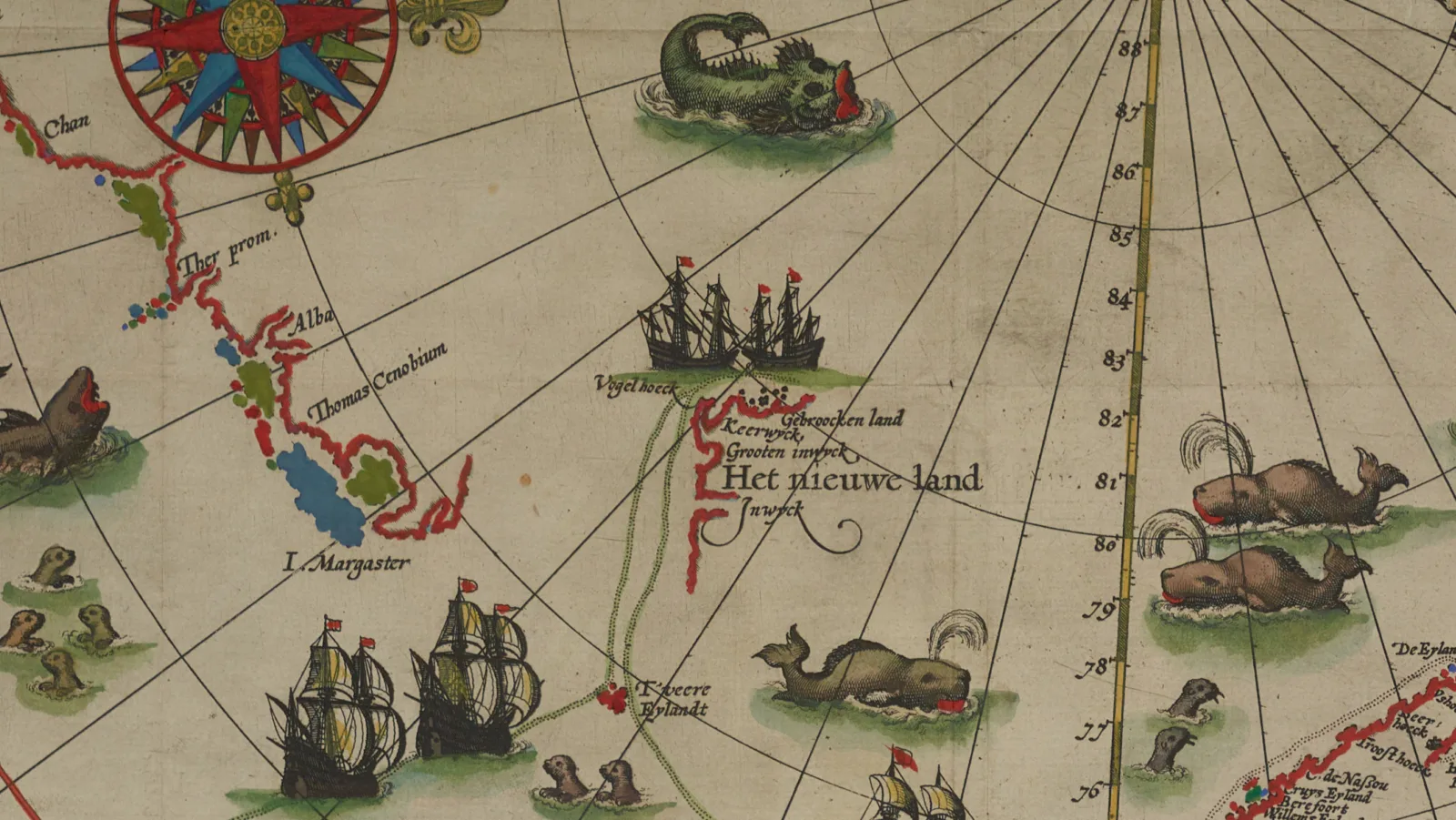

Art and science meet off the coast of Greenland. It sounds like the start of a bad geography joke. But you can see it for yourself on William Barentsz’s 1598 map of the Arctic, one of nearly 700 maps in the Franco Novacco Collection here at the Newberry. The map has plenty to catch your eyes, from ornate compass roses to sea monsters to elaborate frames for the map’s text.

As if fearing we might be too overwhelmed to look too closely, the map offers a literal path into its core. There, a small group of ships gather off the coast of the Netherlands at the beginning of the path of Barentsz’s expedition into the arctic.

By starting in the lower left corner, you can safely follow the green track of Barentsz’s ships from Dutch shores past pods of seals, up into the Arctic circle. As you follow the ships along the path, you can see the scientific advances of Barentsz’s Arctic expeditions.

To the left, you can find the progress in mapping the coast of Greenland. Ahead, you can find the barest hints of a coastline labeled “Het nieuwe land” (literally, the new land)—what is now Svalbard. But on the three other sides of Svalbard, fanciful, artistic sea monsters roar their terrible roars and crash their menacing tails. In these areas beyond the reach of Barentsz’s scientific knowledge, the map relies on its artistry to retain our attention.

For all their otherworldliness, these artistic elements are more than just flourishes. They also help distinguish between land and sea without pretending to establish the precision of a definitive coastline.

You can see this most clearly at the end of Barentsz’s path on Novaya Zemlya. Here, a small house is labeled “Het behouden huys,” noting where Barentsz and his crew were trapped for the winter on their final voyage.

At the house, the coastline abruptly ends. Above and to the right, seals swim close by and a sea monster lurks farther out. Below, the coastline restarts in the more familiar Russian territory alongside a red-coated driver riding a sleigh with reindeer.

Before you say it, I’ll be the grinch. This is not a mythical Santa but a Samoyed. The narrative account of Barentsz’s voyage describes their sleds with “one or two hartes [deer] in them, that runne so swiftly with one or two men in them, that our horses were not able to follow them.”

In fact, depictions of Santa with reindeer and sleigh first appeared much later, in Washington Irving’s satirical A History of New York (1809) and Clement Moore’s “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (1823).

In between this Russian sleigh driver and the seals, the map leaves us without any precise information. All we can know for sure is that the sleigh is on solid ground and the seals are in the sea. The map doesn’t pretend to tell us where sea and land actually meet.

This blend of art and science is at the heart of the Franco Novacco Collection. Novacco was drawn to maps for their “extreme elegance;” and only through that artistry did he come to appreciate their “great historical and scientific importance.” This map lives up to Novacco’s billing. From the maze-like maelstrom to the spouting sea monsters, the big and small details draw us into the map. And the more we look, the more the map rewards our attention with both artistic beauty and the history of polar exploration.

About the Author

David Weimer is the Newberry's curator of maps and director of the Hermon Dunlap Smith Center for the History of Cartography.